There are a few fortunate people who know early on what they want to do for the rest of their lives–and actually find a way to do it. One of those felicitous folks is Bruce Davidson. Born in Chicago in 1933, Davidson first picked up a camera at age ten. By 16, he’d won the Kodak National High School Competition. He studied photography in college and in 1955 his thesis (a series of photographs depicting the passion of college football players) was published in Life magazine.

Over the next six decades, Davidson continued to create images that have been described as “extraordinary for the depth of their feeling and their poetic mood.” After a period of military service (during which he was stationed in Paris, where he met Henri Cartier-Bresson–one of the founding members of the Magnum photo agency), he worked as a freelance photographer for Life. A year later Davidson was asked to join the prestigious Magnum Photos, the international photography agency.

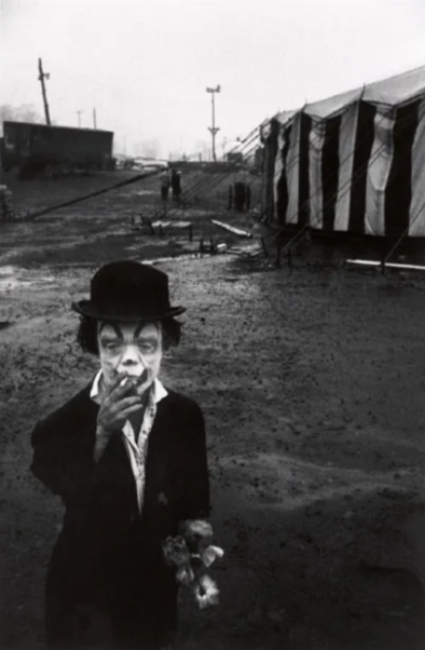

Davidson’s work tends to focus on the situations of marginalized groups of people. He first gained real national attention in 1958 with his series entitled “The Dwarf,” in which he documented the life of a lonely dwarf who worked as a clown in a traveling circus. But it was the following year, with the publication of his series on a group of New York teens, “Brooklyn Gang,” that solidified Davidson’s reputation.

In 1959, two years after West Side Story first appeared on Broadway, street gangs were still much in the news. Davidson had learned about a gang calling itself “The Jokers” from a social worker. He spent the spring following these teens around their neighborhood in Prospect Park and photographing them.

This was, obviously, a simpler and less violent time–an era in which gang members carried zip guns and bicycle chains for weapons. But to the general public of the time, youth gangs were perceived as a savage and aggressive criminal element. Davidson’s photographs revealed them as wary but vulnerable kids whose criminality, for the most part, was one part bravado, one part necessity, and one part alienation.

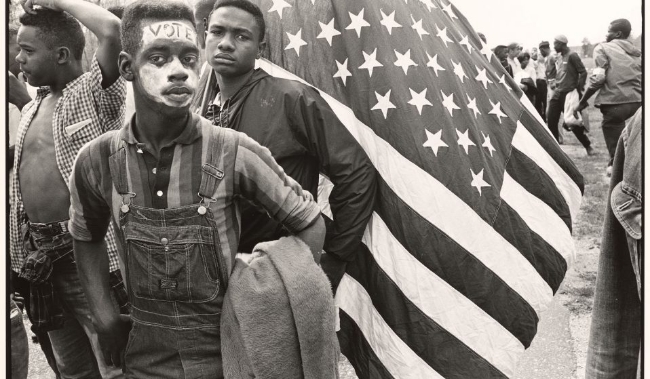

In 1961, Davidson began to document the growing civil rights movement in the U.S. South. A year later he received a grant from the Guggenheim Fellowship to support his work. He spent much of the period between 1961 and 1965 in the deep south. It was a violent period; civil rights workers were beaten, lynched, murdered. Photographers from the north were not looked upon with any affection. Davidson called the civil rights movement the “most meaningful story I ever covered.” Not only did his photographs reveal the horror of the violence to the American public, it also led to a one-man show at the Museum Of Modern Art in New York.

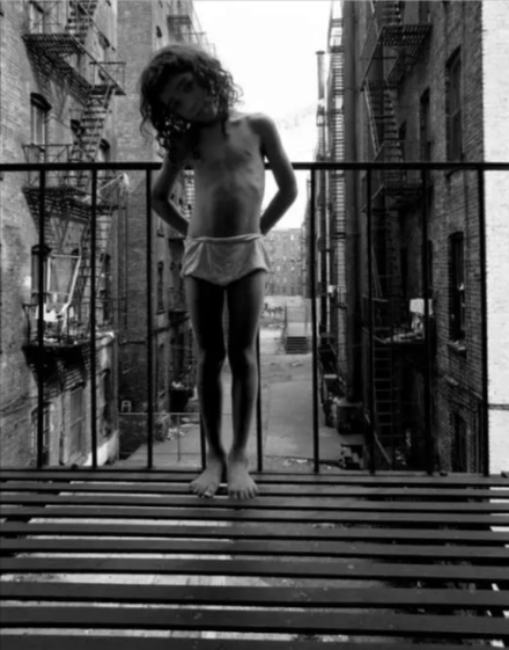

The following year, 1966, Davidson was awarded the first grant for photography given by the National Endowment for the Arts. He spent the next four years documenting life on a single block in East Harlem. His series “East 100th Street, Harlem” resulted in both a book and another show at MOMA; the series of photographs is now widely considered to be a modern classic.

One reviewer described Davidson’s Harlem series as having “a varied formal vitality that expresses the human condition in a lyrical visual language that is his own. We see in his work both dignity and despair; his photography functions as a point where loneliness, compassion, and social concerns are brought into focus.”

Davidson’s compassion is evident in the following photograph of a young girl standing on a Harlem fire escape. The photograph is eerily reminiscent of Sodoma’s famous painting of the martyred Saint Sebastian.

While Davidson’s body of work is not done in the service of advocacy, there is nonetheless a very clear concern about social issues–injustice, racism, crime, urban blight, the collateral damage of untrammeled capitalism. Perhaps the best description of Davidson’s body of work was actually a description of Davidson himself. Henry Geldzahler, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum, said this of Davidson: “The ability to enter so sympathetically into what seems superficially an alien environment remains Bruce Davidson’s sustained triumph; in his investigation he becomes the friendly recorder of tenderness and tragedy.“

The friendly recorder of tenderness and tragedy. Bruce Davidson still lives and works in New York City; when he dies, though, that would be a fitting epitaph.