He was born Gyula Halász in the ancient Transylvanian city of Brassó. In 1902, his family moved to Paris for a year (his father, a professor of literature, had a one year lectureship at the Sorbonne). Given that he was only three years old at the time, he couldn’t have formed any distinct memories about city, but Paris became a sort of romantic fantasy for him. He always wanted to return.

The First World War got in the way. France and the Austro-Hungarian Empire (in which the city of Brassó was located) were on opposite sides of the war. The 17 year old Halász joined a cavalry unit of the Austro-Hungarian army and served until the war ended in 1918. After the war, he briefly studied art in Berlin. That education was interrupted when he returned to his native land to join a short-lived revolution to establish a socialist republic in place of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire. Halász was captured and spent some time in prison.

After the war and the failed revolution, Halász apparently abandoned politics. He wanted to move to Paris, the dream city of his youth. However, the treaty that ended the war also restricted the immigration of former enemies into France. Instead, he returned to Berlin and renewed his studies of art and journalism.

In 1924 Gyula Halász was finally allowed to return to Paris. It was to become his city. He would eventually become a citizen of France, but in truth all he ever wanted was to be a citizen of Paris.

In Paris, he worked as a journalist while practicing his art. His art at that time was painting. Halász had little respect for photography; he considered it to be a craft at best, saying it was “mechanical and impersonal.” Despite his occupation as a journalist, Halász kept bohemian hours. He described himself as a nocturnal creature, prowling the streets of Paris all night, going to bed at dawn. He was apparently unhappy with his attempts to paint Paris by night.

In 1930 a friend…another immigrant from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire…convinced him to try using a camera to create images of Paris at night. That friend was Andre Kertész, also destined to become one of the masters of photography. Halász bought a camera–a 6x9cm Voigtlander Bergheil–and a tripod, and went out one night to shoot photographs.

On that night, it could be said that Gyula Halász ceased to exist. Brassaï was born.

He took his name, of course, from the city in which he was born. But nobody will ever associate Brassaï with a city in Transylvania. His name will forever be linked inextricably with Paris.

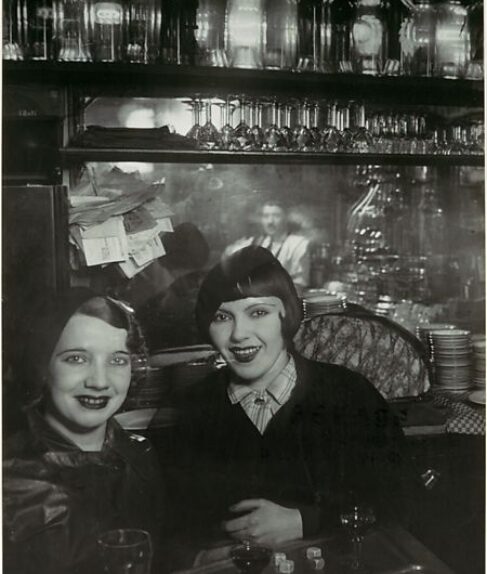

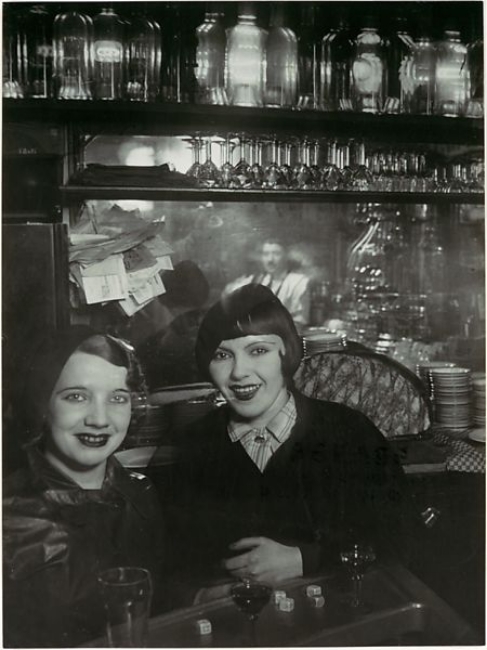

Brassaï took wonderful portraits of his artist friends–Henry Miller, Pablo Picasso, Jean Genet, Alberto Giocometti, Henri Matisse, Salvador Dali–but few people know those photographs. He is undoubtedly best known for his photographs of Parisian night life. He shot the people who inhabited the cafes and bars, lovers clasped in dark corners, prostitutes, opium addicts, vagabonds, hoodlums. Because he was so often on the streets during the hours when all the decent Parisians were home in bed (or in someone’s bed), Brassaï often drew the attention of the gendarmerie. They were skeptical that it was possible to take photographs in the dark, so he began to carry a few of his prints in his camera bag.

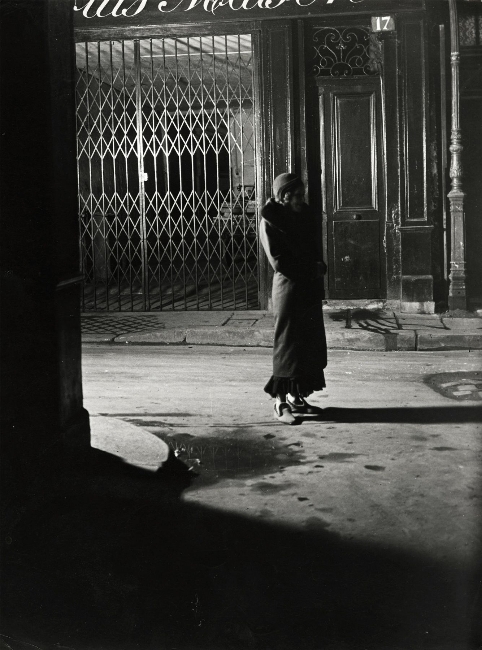

“It is to seize the beauty of the streets, of the gardens, in the rain and the fog, it is to seize the night of Paris that I became photographer.”

That’s a beautiful sentiment and it’s unquestionably true. But it’s also a tad misleading. Brassaï preferred mist and light rain because it minimized the extremes of contrast that were a major problem with night photography. The moisture in the air diffused and softened the light. In perfect bohemian style, Brassaï timed his long night exposures with cigarettes; for shorter exposures he used a cheap, fast-burning Gauloise, for longer exposures he bought more expensive, slower burning American brands.

Long exposures were useful in his exterior night photography, but Brassaï also photographed the people he met inside the cafes and bars. That required a different technique. Flash powder had been used in photography studios for some time, but the smoke and its smell made it undesirable in a public place…especially one frequented by hoodlums. Brassaï became an early disciple of the newly-invented flash bulb. It must be remembered, though, that there was no such thing as flash synchronization at that time. The existing technology didn’t allow the photographer to press the shutter and fire the flash. Instead, the photographer had to open the shutter, manually fire the flash, then close the shutter. That meant that sometimes his subjects…who, after all, were drinking and laughing and kissing and engaging in all the things one does at night in bars and cafes…moved during the exposure. This ‘flaw’ actually contributes to many of the photographs, making them seem more spontaneous.

In 1933 Brassaï published the book that set his name permanently into the cobbled Parisian streets: Paris de Nuit. The book was a huge success–not because it was about Paris, or that it was one of the earliest books devoted to night photography. The success of Paris by Night was due in largepart because it was so obviously a love story. Brassaï’s ongoing romance with Parisian nightlife was–and still is–readily apparent in every photograph.

Brassaï does two brilliant things in his Paris by Night work. First, despite the fact that so many of his photographs involved long exposures that required his subjects to remain still, Brassaï’s work is surprisingly active. There is always something going on in his work. People are doing things. Mysterious things. Romantic things–and I’m talking about romance in the oldest sense of the term. Second, while all photography depends on light, Brassaï also celebrated the shadow. Much of what we love about his work comes from the things we cannot see–from what we imagine lies within and beyond the mist and the shadow.

Brassaï cleverly puts the viewer IN the shadow, and from that shadow we become a part of whatever is taking place in the photograph. He welcomes us into his world, engages our interest, and invites us to share his love for his magical city. And we happily allow ourselves to be seduced.

Many artists fled Paris (and France itself) when the Nazi army invaded the city in World War II. Brassaï remained. Although his sort of photography was restricted by the Nazis and the nature of Parisian nightlife changed dramatically, he remained. He put away his cameras and returned to drawing and painting. When Paris was liberated, he returned to his cameras and continued the love affair.

Later in his life, the man who once had such disdain for photography said this: “The thing that is magnificent about photography is that it can produce images that incite emotion based on the subject matter alone.” In the course of his life he wrote a novel, published nonfiction books, sculpted in stone and brass, created tapestries, painted, drew clever sketches–but he will always be known for his photographs of Paris.

Gyula Halász died in July of 1984, in the week before Bastille Day. Brassaï, however, is immortal.