Arthur Tress was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1940 and grew up in that strange period between the Second World War and what was called the ‘police action’ in Vietnam. Post-war America took a determined grip on ‘normalcy’ and refused to let go. It was a difficult time for people who didn’t easily fit into the parameters of ‘normal.’ That included Arthur Tress.

Fortunately, in New York City ‘normal’ has always been rather loosely defined. His parents divorced when he was nine; his father moved to a well-to-do suburb; Tress and his mother moved to a poor working class section of Queens. In 1952, when he was twelve, his father gave him a Kodak camera. It was the first of many cameras he would own and use. Tress began to photograph the dilapidated buildings at Coney Island. He spent time at a local community center which had a darkroom and offered lessons in developing and printing.

After high school Tress, supported in part by his father (who was by then a successful businessman living in Manhattan’s Upper West Side), enrolled in Bard College. Bard was then (as it is now) a small, non-traditional liberal arts college. Tress’s studies were almost entirely self-directed, and he was required to attend few organized classes or take many exams. He studied painting and ethnography, while continuing to shoot photographs for his own pleasure. He also became interested in film-making; after graduating from Bard in 1962 (with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree) he moved to Paris to study cinema at the Institute des Hautes Etudes Cinematographique. The Institute, however, was a more traditional school, and Tress quickly became disenchanted. He dropped out and for the next six years he wandered through most of Europe, much of Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Japan, and Latin America. Tress didn’t return to the U.S. until 1968. He was 28 years old.

Although he had partly supported himself during his travels by shooting documentary photographs, he hadn’t considered photography as a serious career. The photographs he’d taken previously were primarily ethnographic, intended to show what life was like for the people in the various cultures he visited. On his return to the U.S., however, Tress began to consider the more aesthetic potential of photography. Rather than merely documenting the world he saw, Tress began to use photography as a form of interpretive expression.

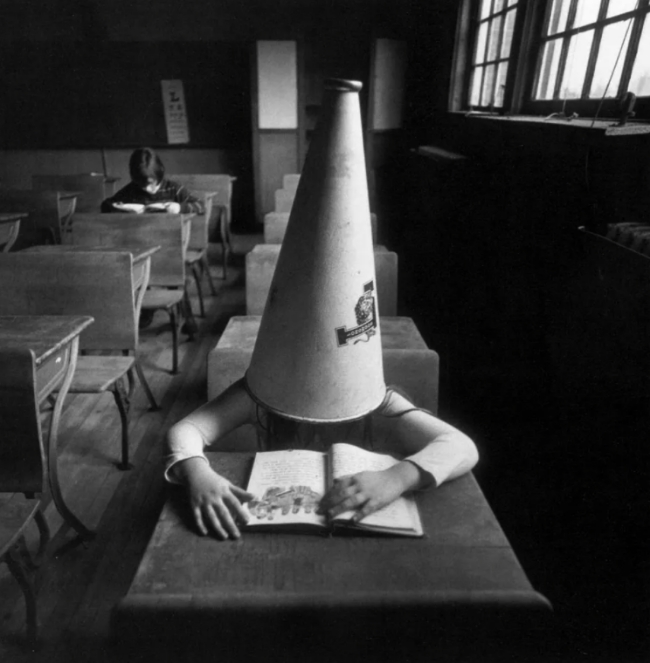

He decided to do a series of photographs exploring the dreams of children. He interviewed a number of children about their most memorable dreams and nightmares. Using the children as subjects, he tried to visualize their dreams. The result was a peculiar melange of semi-surreal imagery depicted in a rather documentary fashion. The photographs were published in a book entitled The Dream Collector.

The singular genius of the series is that Tress approaches the fantastical notions of dreams through what appears to be a straightforward documentary style. He treats dreams almost as another form of ethnography, as if examining dreams were no different than examining the circumcision rituals of the Dahomey tribe or the practices of Hindu ascetics.

The dreams explored by Tress are diverse, but common. Being buried alive. Flying. The humiliation of failure in the classroom. Monsters looking in the bedroom window. Being lost or separated from everybody you know through a natural disaster.

Tress described The Dream Collector like this:

“The purpose of these dream photographs is to show how the child’s creative imagination is constantly transforming his existence into magical symbols for unexpressed states of feeling or being.”

I have absolutely no idea what that means. It sounds suspiciously like the typical artist’s meaningless blather. I don’t think it tells us much about his work, but I do think it offers us some insight into Tress himself.

Tress seems to perceive the world through the eyes of a mystic. He apparently sees still photography as almost an arcane act. He has written that a photographer is “…a kind of magician, a being possessed of very special powers that enable him to control mysterious forces and energies outside himself….[who can] can foretell the potential movements of his subjects and perhaps even by mental intimidation and expansion actually causes them to happen.” Although I’m personally inclined to see this as somewhat delusional, the fact remains that this view of the world has given Tress’s work a sort of internal consistency. Even though his subjects and themes may range widely, there remains a stable, congruous emotion through it all. That emotion is a sort of familiar reverence, a sort of comfortable awe.

Tress has stated that for five thousand years art was created with the intent to inspire awe. That intent, he suggests, has been diluted. “Where are the photographs we can pray to, that will make us well again, or scare the hell out of us?” he asks. Tress has attempted to make that sort of photograph.

In the 1970s and 1980s Tress created photographic series of astonishing diversity. In addition to his more surreal and magical work, he also began to use photography as a method to acknowledge and explore his homosexuality. His work with male nudes tends to be more traditional, and while it is often beautiful and sensual, it generally lacks the playful exaltation of the mystical that saturates his best work.

Tress has also created very engaging series involving still-life assemblages. For example, in his Fish Tank Sonata Tress used an antique aquarium and a bunch of kitschy figurines and knick-knacks from the 1940s and 50s to create a narrative series about an Odysseus-like character who returned home after a long voyage to find everything changed and in disorder. He has also created room-sized collections of found objects, which are carefully arranged coated with spray paint before being photographed. His most recent work involves nearly abstract studies of skateboarders and strangely documentary images of men and boys who play paintball.

With the exception of his nudes, all of Tress’s disparate work seems to retain a consistent subcontext: the world is awful and full of awe, life is temporary and beyond our understanding, so we must bring our own meaning to it. That meaning can be found in anything from sports to prayer to science.

In a very real way, Tress’s inarticulate mysticism is imbued in his photographs, and one can see evidence of it throughout his work. He believes in the child as a sort of privileged witness. He believes in oppression as a constant condition against which everybody must struggle. He believes in the release from oppression, and that death is always the final resolution.

That sounds grim. It’s not–or at least not entirely grim. If you examine his work, Tress always seems to suggest that liberation is possible and perhaps even inevitable. The hockey player is protecting himself. The old man is about to be released from his aged body. The dunce cap can be removed, and the lost child is climbing out into the light.

“Photography is my method for defining the confusing world that rushes constantly toward me. It is my defensive attempt to reduce our daily chaos to a set of understandable images…I need it to survive.”

No mystical jibber-jabber there. Just the acknowledgment that it is possible, in a chaotic world, to find some form of clarity.