In 1935, during the Great Depression, the U.S. government tried an experiment. It created the Resettlement Administration, which was intended to relocate poor urban and rural families into planned communities, called ‘green towns.’ The program was intended to create small, planned communities on the outskirts of cities, with incorporated green spaces with areas for people to live, work, and play. That administration hired a few photographers to document the resettlement program.

A year later the Resettlement Administration was renamed the Farm Security Administration. Only three of the planned communities were built and populated, but the photographers were kept busy documenting the lives of the poor. Many of the best American photographers of that generation got their start working for FSA, including Walker Evans, Gordon Parks, Dorothea Lange and Esther Bubley (who was featured in an earlier salon).

John Vachon was not actually hired by the FSA as a photographer. His initial job title was “assistant messenger.” His actual function, though, was that of a file clerk. He read the hand-written notes made by the FSA photographers about their photographs, used those notes to write captions on the backs of the corresponding 8×10 prints, then filed the prints. Vachon had no interest in photography or the photographs he was filing. If he looked at the prints at all, it was to be sure the photograph matched the caption he was about to write on the back.

Over time Vachon began to feel a sort of paternal pride for the archive of the FSA photographs. He recognized it as an important historical artifact. He created his own filing system and began to develop ideas about the sorts of photos that were needed to keep ‘the File,’ as he called it, well-balanced. He knew what geographical locations were under-represented and which ones were over-saturated. He knew whether there were too many photographs of grain silos or not enough photographs of people working in fields. He was able to see ‘the File’ as a collective whole, not just as a series of individual images.

The legendary Roy Stryker, the FSA administrator who hired the photographers and sent them off on assignment, one day said to Vachon “When you do the filing, why don’t you look at the pictures.” And Vachon did. A few months later he asked Vachon if he could borrow one of the FSA cameras. Stryker handed him a Leica, and the young Vachon began to photograph his neighborhood. The FSA photographers saw his interest grow and encouraged him. Walker Evans gave him lessons on how to use the large format 4×5 cameras.

Stryker began to send Vachon out on short assignments with the photographers as an assistant. Two or three days in Virgina, a week in the Potomac River Valley. Finally, in 1938, Stryker sent Vachon on assignment to Nebraska. Alone. For a month. In the winter.

Vachon loved it. Stryker’s approach to the work suited him perfectly. Half of his time was spent meeting with local FSA staff and following them around, photographing the projects in which they were involved. The other half was spent driving around and photographing whatever he thought should be in ‘the File.’

“It was just a case of every morning looking at the road map. Well, I would drive to a town because I liked the sound of the name. There was a place in North Dakota called Starkweather, and it seemed that there should be some great pictures there so I went there.”

His intimate knowledge of the FSA archives (‘the File’) dictated the individual photographs he took. If ‘the file’ was short on pictures of school houses or students, Vachon would photograph school houses and students. His approach tended to be direct and simple, purely documentary. But he had a knack for finding the image that would accurately document the reality of people’s lives while still tweaking the heart of the viewer. For example, he would take the standard photograph of a school house, but he would also take a photo of the students’ lunch pails lined up on the cloakroom shelves. The larger lunch boxes of the students who were better off, the battered lunch pails of the majority of farm children, and paper bag of the one student whose family couldn’t afford a pail. That one telling detail added emotional depth to the photograph.

When he returned to Washington, DC after a month, Vachon was able to caption his own 8×10 prints and add them to his beloved ‘File.’ He continued to do both jobs–file clerk and photographer–for the next three years. It wasn’t until 1941 that he was officially given the title of photographer. Even then Vachon continued to maintain the FSA archives until 1942, when another man took over the filing. In an interview shortly before his death in 1975, Vachon still clearly resented the fact that the new man changed his filing system.

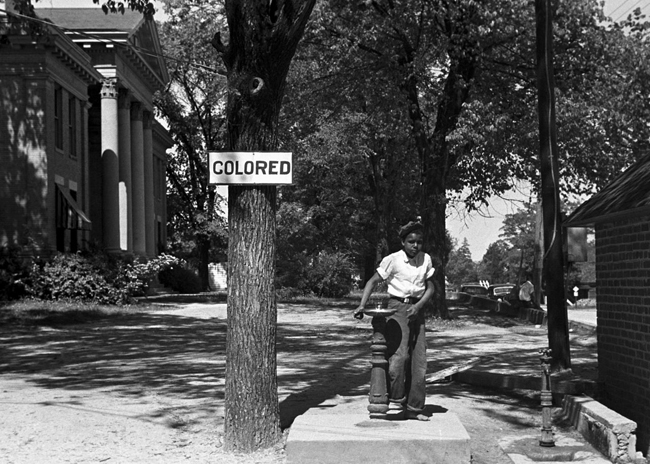

Because the purpose of the FSA photography section was to document poverty in America during the Depression, Vachon spent most of his time with the poor and working poor. Hardscrabble farmers who were just barely getting by and dependent on government assistance. Miners who were ruining their health in badly ventilated, under-regulated mines. Children who were only able to go to school and get a basic education because it was free. Migrant workers whose diets consisted of the produce they picked that was not fit for sale. Families driven out of their homes by poverty or off their farms by drought.

The FSA photographers were, in many ways, idealists. Though the photographs they shot were mostly intended for government use (in news reports, brochures, public information campaigns), Stryker had also given them the chance to use their own initiative and create images that could move people to institute social change. He insured that the major magazines of the day had free access to FSA photographs.

Even though they tended to work alone, the FSA photography section developed a strong esprit de corps. As a unit they felt they were documenting an important attempt to improve the social conditions of their fellow citizens. One facet of their idealism and camaraderie was a commitment to the documentary purity of the photographs they took. Vachon said they were determined “…that photographs should never be fake, that we only take the real thing, we don’t doctor things up, make people do what they’re really not doing.”

The Great Depression ended with the onset of the Second World War. Suddenly there was a tremendous demand for both skilled and unskilled labor, and since so many men had joined the military, there were fewer men to fill those jobs. With the economy recovering, the FSA mandate to document poverty became less important. In 1943 the photography section of FSA was subsumed by the Office of War Information. A year later it was disbanded.

Vachon became a staff photographer for LIFE magazine, and then later for LOOK magazine. He continued to create excellent work, but photography became just a job. “At LOOK you work with a writer,” he told an interviewer. “You’re thinking of a layout, you’re thinking of six pages, of a beginning, a middle and an end.” In contrast, with FSA “we weren’t doing stories; we were taking pictures.”

But Vachon knew weren’t just taking pictures. Nothing he did after his years at the FSA mattered as much to him. After LOOK magazine went out of business in 1971 Vachon became a freelance photographer. In 1973, he won a Guggenheim fellowship. In 1975 he was a visiting professor at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. But it was his FSA work that meant the most to him.

“I think at the time we were doing it, we had quite a bit of conviction that we were doing something important.”

John Vachon died of cancer in 1975 at the age of 60.

While many of the individual photographs taken by FSA photographers have become iconic images, to Vachon the real value and importance of FSA was the creation of ‘the File,’ the archive of all their work. In the end, Vachon’s cherished ‘File’ contained more than 164,000 negatives and 77,000 prints made by 23 photographers over the course of eight years. Of those, 11,157 were made by John Vachon. It is the most comprehensive record of a segment of American society ever created. It’s a legacy that has long outlived the original purpose of the program.