During his career William Gedney only had one exhibit of his photography. He only had a single photograph published in a magazine in the U.S. He never worked on assignment. In fact, outside of a few other photographers, a handful of gallery curators, and a small number of grant managers at art councils, Gedney was unknown. Sad to say, that’s still largely the case.

Gedney was born in Greenville, New York in 1932. He moved to Brooklyn in 1951 to attend the Pratt Institute of Art, where he developed a passion for photography. He took a cold-water flat near the school and lived there for the next 20 years. By living modestly, Gedney was able to devote himself to photography. After graduating from Pratt in 1955, Gedney worked briefly as a layout artist for Condé Nast publications and later at Time magazine. At each job he saved his money; when he’d accumulated enough to live on for a period of time, he quit so he could concentrate on his photography.

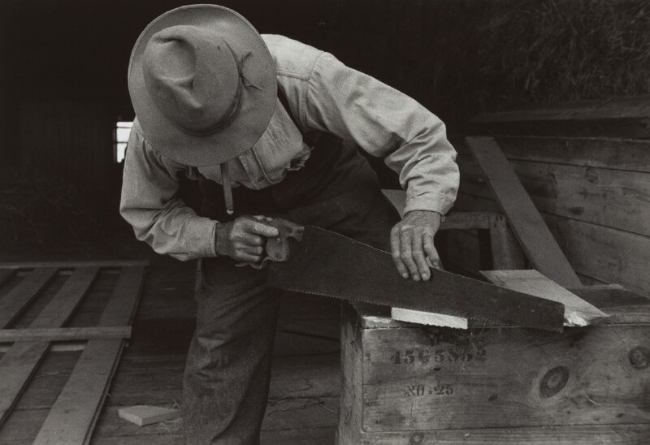

Among Gedney’s earliest subjects were his grandparents and the farm on which they lived in Norton Hill, NY. The process he developed when photographing his grandparents would shape the way he worked throughout his career. Living with his subjects, earning their trust, staying quietly on the perimeter of their lives, so quietly that his subjects soon stop paying attention to him. It appears this is also where he developed his photographic style–modest, gracious, compassionate, but with a flair for the dramatic and what has been called “an almost preternatural instinct for composition.”

In 1964 Gedney left Brooklyn and traveled to Leatherwood, Kentucky, the home of the Blue Diamond Mining Camp to photograph mining families. Initially Gedney stayed with the head of the local United Mine Workers Union, then moved in with the Cornett family—a laid-off mine worker, his wife, and their twelve children. He lived with them for a week and a half, photographing them. It’s very telling that Gedney continued to stay in touch with the Cornetts and returned to live with—and photograph—the family again in 1972.

Gedney was neither the first nor the last to photograph mining families, or any community of marginalized people, but his images lack the paternalism or political slant that’s so common in such photographs. His intent wasn’t to document a family living in poverty, it was to photograph a family; poverty was the condition under which they lived, but it wasn’t the defining condition.

In a very real way, the tempo of the Cornett family life was little different from that of Gedney’s grandparents on their farm. There was always some task or chore than needed to be done, but no rigid schedule for doing them and the cadence of the day was dictated by the rising and setting of the sun rather than by the clock. Gedney’s photographs reveal a clan who, for the most part, are engaged in the fundamental enterprise of just getting by, but he manages to find moments of surprising grace and humanity. As he wrote in his journals, “I prefer the ordinary action, the intimate gesture, an image whose form is an instinctive reaction to the material.”

Early in 1966 Gedney was awarded a year-long Guggenheim fellowship with the nebulous mandate to photograph ‘American life.’ He used the money to buy an early predecessor of the modern SUV—a Suburban Carryall. He left Brooklyn with no particular plan, no particular destination other than to drive across the U.S. and photograph the people and places he saw.

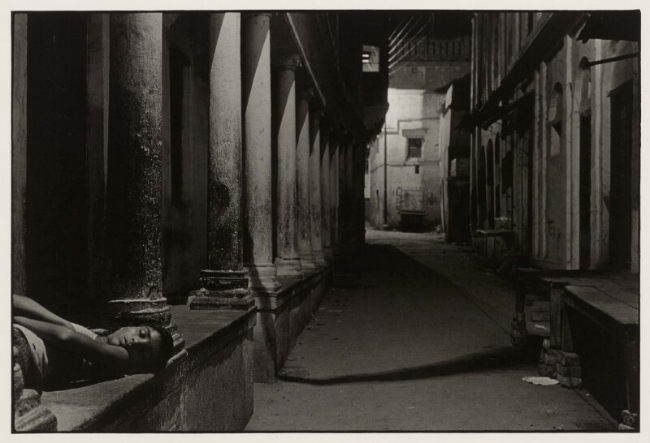

He photographed any aspect of American life that intrigued him. Suburban teens talking on the telephone, Mexican migrant workers in the fields, small town shops and storefronts, ordinary people living their ordinary lives. He also began a series of night photographs of the towns he passed through. Again, this was not an original idea. Surely Gedney, through his studies at the Pratt, was aware of Brassaï’s photographs of Paris by night. Like Brassaï, Gedney’s imagination was sparked by the way streetlamps both illuminated and masked the world. He never stopped shooting night photographs; he would continue to do so when he eventually returned to Brooklyn, and still later in India and the cities of Europe.

Five months after he left Brooklyn on his Guggenheim-sponsored odyssey, Gedney arrived in San Francisco. In 1966, San Francisco had just begun to manifest itself as the center of hippie culture. Young men and women were drawn to the city from all over the U.S. Gedney was 34 years old at the time, much older than most of the newcomers to the city. But once again, he utilized the same approach of immersing himself into the community he wanted to photograph. He settled in a free squat/crash pad with half a dozen other people and remained there for the next three months.

Gedney shot thousands of frames over those three months documenting the burgeoning hippie movement. He was perhaps the first photographer to record the new Digger culture—the collective who supported the hippie movement by finding free food, preparing free meals, locating free housing, and providing some free fundamental social services. Years later, when a curator at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art came across Gedney’s hippie/digger photographs, she was amazed that such a collection existed, and doubly surprised that it had gone unnoticed for so long. “It wasn’t flashy,” she said of Gedney’s work, “it wasn’t self-promotional, it wasn’t extreme in any way. It was just really gracious, humane, modest work, and very good.”

Two years after he set out on his cross country trip—and four years after his time in Kentucky with the Cornett family—Gedney was given his first and only solo exhibition. The Museum of Modern Art displayed 44 prints of his Kentucky and Guggenheim work in one of their smaller galleries.

A year later, in 1969, a number of Gedney’s photographs from San Francisco were collected for publication in a book to be called A Time of Youth. The book, however, was never published. This became a recurring event in Gedney’s professional life. He had shot portraits of fifty famous composers for a book on the subject, but the writer hired to prepare the text failed to deliver it. Many of his photographs of his journeys through India were gathered and curated for a monograph, but the publication of the book never materialized. The quality of his work was recognized, but events conspired against him.

Gedney was eventually hired to teach at the same university where he’d studied—the Pratt Institute. This allowed him to continue to his work and to travel. He traveled through Europe; he went to India with the plan to travel from Delhi to Calcutta, but ended up spending four months in the holy city of Benares (also known as Varanasi) on the Ganges.

Everywhere he went, of course, he shot photographs. What I find most wonderful about the work he produced in Europe and India, is that it’s not very much different from the work he produced in Brooklyn or Kentucky or San Francisco. The people may look different and the locales may seem more exotic, but the same humanism and compassion is present. Gedney’s work remains eloquent but simple whether he is photographing a man asleep on the streets of a city in India or a woman having a drink and a laugh in O’Rourke’s bar in Brooklyn. His work is always about other people, never about himself.

Just as important for students and historians, Gedney took notes. He was a scribbler of the first order, recording everything he did photographically as well as his thoughts on what he was photographing. He noted what sorts of film he used, what camera settings he used, how many shots he took. He describes what he saw in his travels, he discusses the photographs he took in his own Brooklyn neighborhood and at his favorite bar, he writes about whatever is on his mind. On one page Gedney will note that he used his Leica M3 to shoot 24 frames of Tri-X film at Tracy’s Do-Nut Shop exposing the interior shots for 1/50 of a second at f2.8, and on one of the following pages he’s written the lyrics to a Bob Dylan song. Over the years, Gedney filled more than 30 notebooks.

Gedney died in 1989. He left his photographs and notebooks to his friend and fellow photographer Lee Friedlander, who later donated them to Duke University. All of his work—his photographs and contact sheets, as well as his notebooks—are available for viewing through the university’s Special Collections Library. They are well worth examining. The four images presented here fail to give the true scope of the diversity of Gedney’s work.

In one of his journals, Gedney quotes the composer Béla Bartók: What matters most of all, is to penetrate into the pulsing life of the people themselves, to become imbued with their way of living, and to see their faces when they sing at their weddings, harvests and funerals. It seems to me the photography of William Gedney embodies that spirit.