Let me start with a confession. When I first came across Juliana Beasley’s work, I wasn’t very impressed. The photographs I first encountered were from her first book, Lapdancer, which is usually described as a gritty photographic journey into the underbelly of strip clubs.

My response was always the same: please, spare me another gritty photographic journey into the underbelly of just about anything. Let’s face it, grit has been done to death. Underbellies, done to death. Sex workers of all sorts, done. All of it, done and done.

While Beasley’s Lapdancer photographs have an authenticity that gives them a bit more gravity than the usual images seen in this narrow ouvre, they didn’t strike me as particularly distinctive. That book, published in 2003, put Beasley on the photographic map, but I didn’t give her any real consideration as a subject for these Sunday Salon essays.

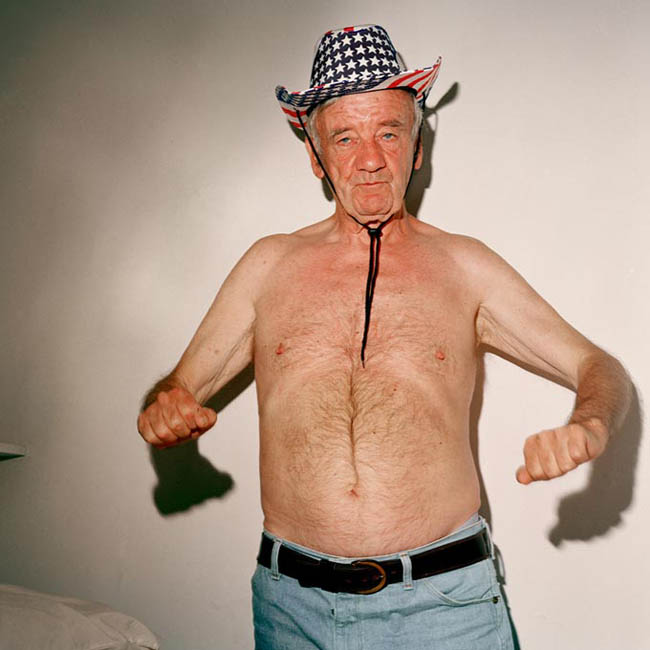

And then I saw the following photograph:

Beasley was born into a middle class Philadelphia family in 1967. She became interested in photography as a young girl, looking through the family photo albums. She attended New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and graduated in 1990 with a bachelors degree in photography. Afterward she supported herself by doing journeyman photography work; she worked briefly making prints for Annie Leibovitz, she sought out freelance assignments covering the city’s club life.

As might be expected, money was tight. Beasley wanted to make enough money “to travel abroad and work on my documentary portfolio.” So in 1992 she began to work as a stripper. “Shortly after, I realized that I could make enough money to pack away for the future and began dancing full time.” Part of the attraction of strip clubs for Beasley appears to have been the fact that it existed outside the circle of her art school friends. There was no overlap between the strip club and the art gallery. There’s a certain freedom in developing an entirely new life situation.

There is some confusion about how the Lapdancer project began. It is, of course, only natural for a photography student to want to photograph an interesting venue. In one interview Beasley said, “The moment I started dancing, I wanted to photograph what I saw.” She added, “At first I used to carry my Contax T2 in my duffle bag, stashed amongst all my lingerie and schoolgirl plaid skirts.” In a later interview, however, Beasley said the project “took about eight years to unfold, although most of the actual picture taking didn’t happen until the end of the project.”

Her various accounts of the concept behind the photographs are equally confused. “I wanted to make an ethnographic book based upon the untainted and least subjective viewpoints as possible.” “I decided to focus on the exchange of love and affection for money.” “I didn’t want to glamorize the life nor did I want to produce another account of stripping as a sociological phenomena. I wanted to capture dance.”

Having seen some of the photographs from Lapdancer I’m not convinced her intent was to “capture dance.”

My impression is that Beasley had only a vague idea of what she wanted when she began shooting the Lapdancer photographs, and it was only after she began to consider publishing the photos that she started to search for an underlying theme to give the project coherence. That’s a perfectly valid approach, even if it means Beasley wasn’t always consistent in her explanations of her reasons for shooting the photographs. The important thing is she understood that photography was a means for both self-expression and engagement with marginalized communities. And she knew that’s what she wanted to do.

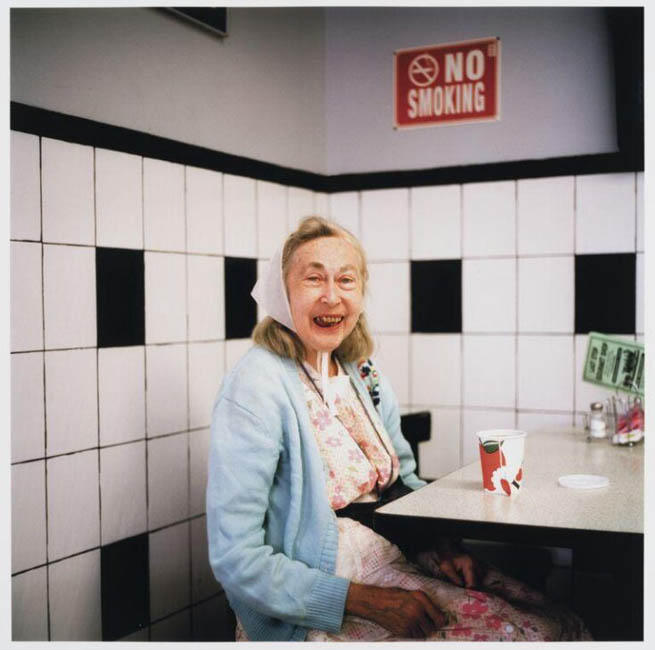

Her next project, Last Stop: Rockaway Park, was enough to make me easily forgive the unexceptional photography of Lapdance and Beasley’s dithering about its meaning. I am so completely taken with these images that I can forgive Beasley just about anything.

For those of you unfamiliar with New York City, Rockaway Park is about 20 miles from Manhattan. Leave Manhattan, pass through Brooklyn and Bensonhurst, keep going past Coney Island and Brighton Beach, until you arrive on the peninsula that was once called the “Irish Riviera.” A popular holiday resort in the 1830s and the location of an amusement park built in 1901, the Rockaways (there are several communities bearing the Rockaway name) have fallen on hard times. Much of the area was razed during a 1960s urban renewal project, but the ‘renewal’ facet of the project never quite came together. Now it’s home to a population suffering from massive unemployment, a high rate of mental illness, and a level of drug and alcohol addiction that is staggering.

Beasley’s Rockaway project began in much the same way as Lapdancer, almost by accident. Shortly before the publication of the earlier project, she went to the Rockaways with some friends, one of whom was working on a book about recreation in and near New York City. As they walked along the boardwalk they saw a bartender leap over a counter with a baseball bat in his hand to chase away an unwelcome guest. “I knew I had arrived,” Beasley said. “I felt immediately at home.”

Unlike the Lapdancer project, however, this time she had a fairly clear idea why she was shooting the photographs, what sort of photographs she wanted to shoot, and what the project was actually about. The project was “…not about alcoholics and mental illness, it is more about giving dignity and a face to people who are often skirted to the side and invisible in the world.”

The week after witnessing the bar incident, Beasley was back in the Rockaways with her camera. She began by photographing a homeless woman with a history of schizophrenia. This woman, according to Beasley, “…amazed me with her will to survive despite her never-ending consumption of cheap and potent beer…. Through this one woman I met one drinking buddy, and then the circle just grew larger.”

This immersive sort of photography can only be accomplished in long-term projects. That’s especially true when dealing with marginalized groups, who tend to be suspicious of outsiders. It’s a modality that seems to suit Beasley, who says “I see the way that I photograph as being straightforward with a little touch of experimentation and probably a lot more chance and a bit of unconscious behavior.”

Although her personal aesthetic is different, Beasley’s Rockaway project reminds me of the work of Anders Petersen, who spent three years in the 1960s living with and photographing the inhabitants of Hamburg’s notorious Reeperbahn district. Both photographers have the same sort of affection for the disenfranchised members of society. More importantly, they each had the native talent to show that affection in their photographs. Both seem more interested in the people they photograph than in the critical response those photographs might bring.

Here is Petersen: “To me, it’s the encounters that matter. Pictures are much less important.” And here, Beasley: “I just like to meet people who do things a little differently…and I like to make people, often marginalized for whatever reason, to feel whole and connected.”

I rather doubt the people Beasley photographs are actually made to feel “whole and connected” through her interactions with them, but I suspect she genuinely wants them to feel that way. What matters most to me, though, is that through her photographs Juliana Beasley is able to let others sense the compassion and affection she feels for the people she photographs. There is no condescension in her work, and no judgment. That is a rare gift for a photographer, and a gift for those of us who get to see her work.