Sarah Moon is often referred to as an “impressionist” photographer. Her work is noted for a sort of softness, a vagueness that’s suggestive of the impressionist painters. Moon comes by this style naturally—she is extremely near-sighted.

“It was only when I started photography that I became aware of it. People would say to me: ‘But it’s not sharp!’, and I didn’t understand because that was the way I saw things. I had never worn glasses in my life.”

This may be my favorite thing about Moon. Even after she was fitted for glasses, she continued to follow the stylistic path she began on, producing moody, dream-like images that seem to exist outside of normal notions of time.

This impressionist style became her signature, and although her work matured and evolved somewhat over time she’s never quite escaped the reputation she earned in her early career. Her work has been called feminine, enigmatic, overly pretty, nostalgic–and it often is. It’s also a style that’s been copied and mimicked frequently.

There is some confusion about her origins: one interviewer claims Moon was born in England in 1940, another says she was born in France in 1941. Everybody agrees, though, that she began her career in front of the camera. From 1960 to 1966 she worked as an haute couture model both in England and on the Continent. She found that work dull; the photographer seemed to be doing all the interesting work. So in 1967 she moved to the other side of the lens, and never regretted the decision.

Not surprisingly, Moon initially concentrated on fashion photography. Unlike many photographers, she’s never been troubled by commercial work. “I am interested in commercial photography because it provides me with a purpose,” she says. It “submits me to a discipline, which is something I need, because for me it’s easier to do things when I find myself obliged to do them. To do them just for my pleasure would seem irrelevant.“

Yet Moon’s commercial work, whether it was for a fashion shoot, calendar work or other photographic endeavor, generally doesn’t feel or look like commercial work. It has the intimacy and individuality of fine arts photography. She may be shooting for a purpose other than her own, but her own personal aesthetic is apparent in the photographs.

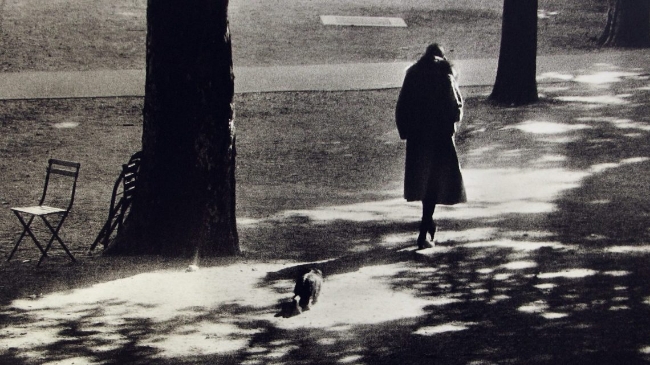

Take, for example, the photograph above. Although it looks like entirely spontaneous, it was actually quite deliberate–at least on Moon’s part. She gave the model a bit of stage direction, telling her it was time for her to go home. As she turned to walk away the little dog followed her and Moon snapped the photo. The result is a timeless image; it could have been shot in the 1930s, it could have been shot yesterday.

Moon finds the objections made by some photographers against ‘staged’ photography to be inane. She feels all photographers stage their photographs to some extent. The photographer chooses the place, selects the angle of the camera, decides on what elements are in the frame. “When you say ‘Don’t move!’ you direct,” she says. It is, of course, impossible to shoot fashion work without some significant staging.

Much of Moon’s early fashion work was presented in muted sepia tones, which she has described as the “tone of memory.” She frequently relied on distressed negatives to give the image an aged feel.

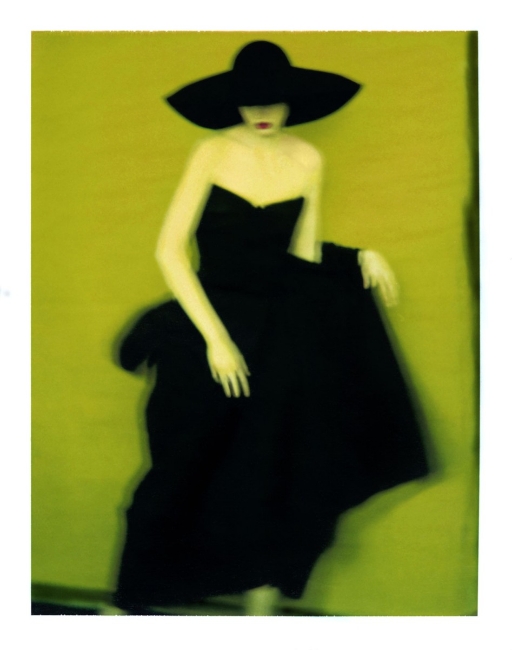

“I believe that if I didn’t work in commercial photography, I would never work in color. I don’t really like color. To make it work for me, I have to mess with it.”

She believes color imagery contains too much information. “What I aim at is an image with a minimum of information and markers, that has no reference to a given time or place, but that nevertheless speaks to me, that evokes something which happened just before or may happen just after.“

Like so much of the modern fashion photography published today, the images Moon produced were less about calling attention to a specific product than they were about generating ‘buzz’ for a fashion line or the magazine publishing the spread. Many of her fashion photographs could pass for portraiture.

Moon was so successful at imposing her personal aesthetic on the fashion world that in 1972 she was asked to shoot the photographs for the famous Pirelli calendar. She was an extraordinary choice, partly because no woman had ever before been hired for that assignment and partly because, as Pirelli acknowledged, Moon was “not well liked by journalists.” She was considered cold and moody. Moon chose petite models rather than the voluptuous women who had previously graced the calendar. Many of Pirelli’s calendar customers complained that the 1972 calendar had ‘lesbian’ qualities.

This seems to emphasize the odd relationship Moon has with commercial photography. She feels commercial work gives her some sort of impetus and suggests it gives her implicit permission to take the sort of photographs she feels would be ‘irrelevant’ otherwise, but at the same time she dislikes the strictures her commercial clients place on her–like the need to work in color or the necessity of meeting a client’s publicity needs.

Later in her career Moon began to take on more personal projects and to expand her creative endeavors. She started to make short document films, some of which also included her own still photography. Circus, based on the tale The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen, was a small success. Her film Henri Cartier-Bresson Point d’interrogation, released in 1994, was considered very influential by many photography students.

Although she attained a certain amount of renown among fashion photographers and, to a lesser extent, in the realm of fine arts photography, Sarah Moon has never gained much public attention. But I rather think she’d be content with what she has achieved in her career. In the end, it seems what Moon most wants to achieve is an emotion—in the viewer, yes, but mostly in herself. She wants to reduce all the extraneous details from an image so that what remains is something elemental.

She has said that when she works on a set loaded with props, her first act is to toss most of them out.

“I would like to get rid of all the make-up so that the make-up would be forgotten, to take off all the clothes. I spend my time eliminating things with the hope that there will be something left that will surprise me, that will make me forget I am in a studio, in front of a model I have booked, on a set on which I have spent hours fussing…. Ultimately, what makes me press the shutter is a feeling of recognition. As if suddenly I felt: ‘Yes, that’s it.'”

That sort of delicate balance between the staged and the spontaneous is what makes Sarah Moon’s work worth studying. Her work itself may be somewhat predictably pretty and nostalgic, but the attitude with which she approaches her work is magnificent. Reduce what isn’t needed, be alert in case the hoped-for unpredictable moment occurs, seek out that gut-satisfying emotion that lets you know you’ve got something special. It doesn’t matter if you succeed every time, or every fifth time, or every twenty-fifth time; what matters is looking for it and being open to it when it arrives.

As Sarah Moon said, when it all comes together “I ‘recognize’ something that I had never seen until that moment, that is beyond all my intentions.” And that’s something we can all understand.