Two critical facts about William Christenberry. First, he was born in Alabama in 1936. He spent much of his childhood summers in Hale County, Alabama–a poor, rural county in the west central part of the state. Second, in 1944, when Christenberry was eight years old, his parents gave him and his sister a joint Christmas gift: a Brownie camera.

Why are those facts critical? Because Christenberry learned to use that camera, and because Hale County is central to Christenberry’s photographic world. The entire county had a population of only about 25,000 when Christenberry grew up. It’s been in decline ever since. Today the population of Hale County is approximately 16,000.

Like so many Southern artists of his generation, Christenberry left the South as soon as he could. He moved to New York City and began painting large abstract-expressionist canvasses. But like so many Southerners, he soon found himself drawn back to his roots.

Christenberry had begun documenting Hale County with his little Brownie camera in 1958, when he was 22 years old. He’d made simple snapshots of the local buildings and structures he considered might be interesting enough to paint.

When he returned to the South, he resumed that work, but with a different intent. Christenberry had come across the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by James Agee, illustrated by portraits by Walker Evans. Agee and Walker had documented the lives of impoverished tenant farmers; Christenberry decided to do something similar to the physical structures of Hale County.

Christenberry’s main photographic subject has become the American South and the effects of the passage of time on Hale County’s culture and landscape. He returned again and again to the same places, rephotographing them year after year.

The simple snapshots he places he remembered. He returned the next year and photographed the same places. And he did the same the next year. And every year since 1961 Christenberry has returned to Hale County, Alabama and photographed the same places. And while his work became more technically sophisticated (he eventually moved from his Brownie camera to a Deardorff 8×10 view camera), the images remained deliberately simple and artless.

“I’d go into that landscape and make these snapshots. Never did I dream that years later, the world of fine-art photography would see something in these.”

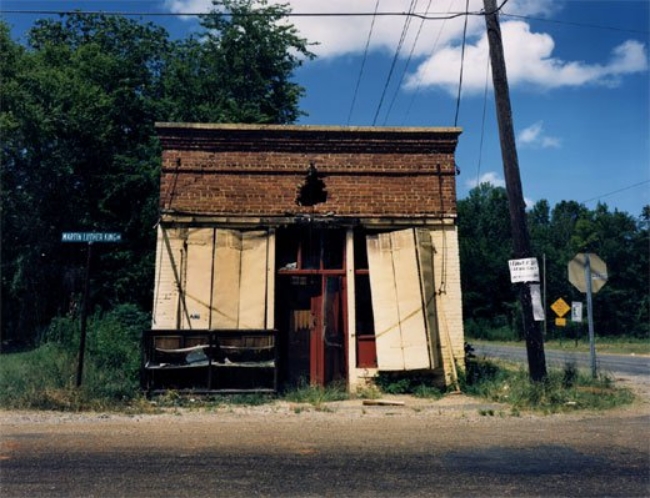

The photographs here show the evolution (and devolution) of a single building. It began as a radio and television repair shop. When that business failed, it became a ‘colored’ juke joint. In order to legitimize the sale of alcohol and the live music, it was necessary for the owners to also sell food. Barbecue. Later, as the South began to desegregate, the joint became better known for its food than for its music. A kitchen fire closed its doors for good, and eventually it was torn down.

Christenberry’s Hale County photographs document the changes of dozens of such locations. Churches, weird little buildings on the edges of town, tar paper shacks, barns, roadside fruit stands, warehouses. It is, in a way, the very artlessness of the photographs that give them power and authority. Christenberry has shown he can create more artistic photographs, yet he chooses to deliberately keep these particular documentary photos simple and snapshotish.

“What I really feel very strongly about, and I hope reflects in all aspects of my work, is the human touch, the humanness of things, the positive and sometimes the negative and sometimes the sad.”

Christenberry’s fascination with these locations has extended beyond photography. In 1974, he began to create highly detailed sculptures of some of the buildings he’d photographed. Also these works accurately reproduce the state of decay of the structure, he insists on referring to them as sculptures rather than models because they’re not based on precise measurements. He has, however, used soil taken from the locations as the bases for the sculptures.

In Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Agee wrote, “[T]here can be more beauty and more deep wonder in the standings and spacings of mute furnishings on a bare floor between the squaring bourns of walls than in any music ever made.” I’m not sure I agree with that entirely, but certain William Christenberry has shown us the beauty and deep wonder of Hale County.