Fazal Ilahi Sheikh came by his interest in displaced people naturally. You could say it was the family business. He was born in New York City in 1965. His father, though, was born in Nairobi, Kenya and his grandfather was born in a part of Northern India that is now known as Pakistan.

After obtaining a degree from Princeton University, Sheikh was given a Fulbright Fellowship to that took him to his father’s birthplace, Kenya. It was during that trip that he began to photograph and document the lives of refugees, displaced people and illegal immigrants. He has continued that project in several nations and across three continents; his photography has taken him to Sudan, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Brazil, Cuba, and the border of the U.S. and Mexico. Since 2001 he has been working on a series of books, all of which are published as part of the International Human Rights Series.

Fazal Sheikh is most definitely not a photojournalist, although he generally works with the classic photojournalist’s tool–a 35mm Leica.. The nature of photojournalism tends to focus on the moment; take the photo and move on to the next story. What Sheikh does is both non-traditional and somehow more traditional. He is not photographing a story; he is photographing the people who lived the story.

For this salon I’m going to focus on only one of his projects: The Victor Weeps, conducted in 1998 in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the region in which his grandfather was born.

The faces of the people photographed by Fazal Sheikh have been shaped by their cultural history, and in order to understand those faces it’s necessary to understand something of the history of Afghanistan. It’s a history of conquest and resistance. That land has been conquered, divided, re-conquered, re-named many times over. The people who live there have always been patient, have always resisted, have always prevailed, but have never truly won. Each time they’ve forced out foreign conquerors, they’ve found themselves living in the rubble left behind.

In 1978 an Afghan communist party succeeded in a coup that overthrew the only stable government Afghanistan had ever known, ending the 40 year reign of King Zahir Shah. Violence followed the coup. In the following year, 1979, the Soviet Army invaded Afghanistan, ostensibly to support the coup leaders. Afghanistan became known as the Soviet Union’s Vietnam. Afghans and Muslims throughout the world gathered together to wage a guerrilla war against the 150,000 Soviet troops occupying the nation. After ten years, during which thousands of Soviet soldiers and tens of thousands of guerrilla fighters were killed and the nation was once again reduced to rubble, the Soviet Army withdrew in defeat.

Fazal visited Afghanistan a decade after the Soviets withdrew. For most of that decade, Afghans and foreign Muslims continued to fight, but instead of fighting the Soviets, they fought amongst themselves to see who would rule. In the end, a coalition of ultra-religious students (called talibs) succeeded in establishing some sense of control. The Taliban ruled Afghanistan according to their interpretation of shari’a, Islamic law.

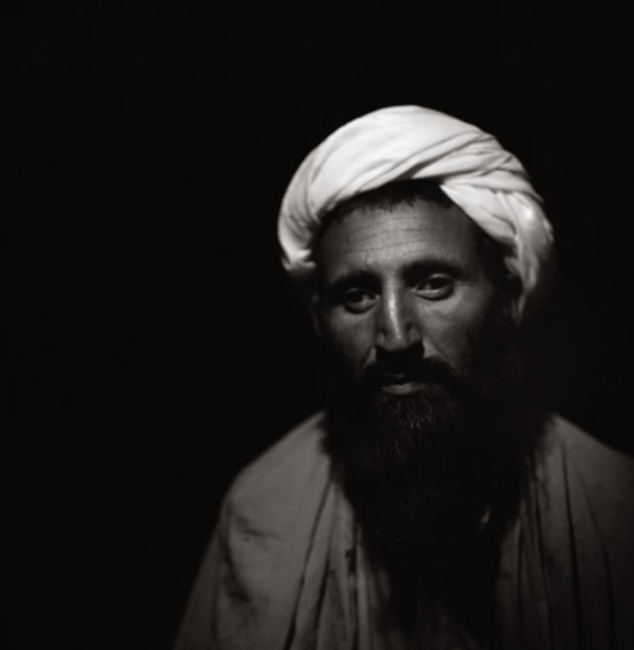

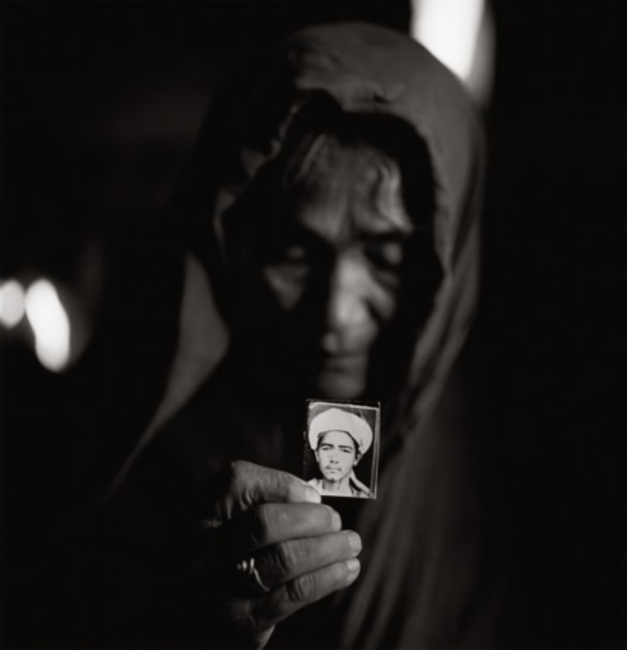

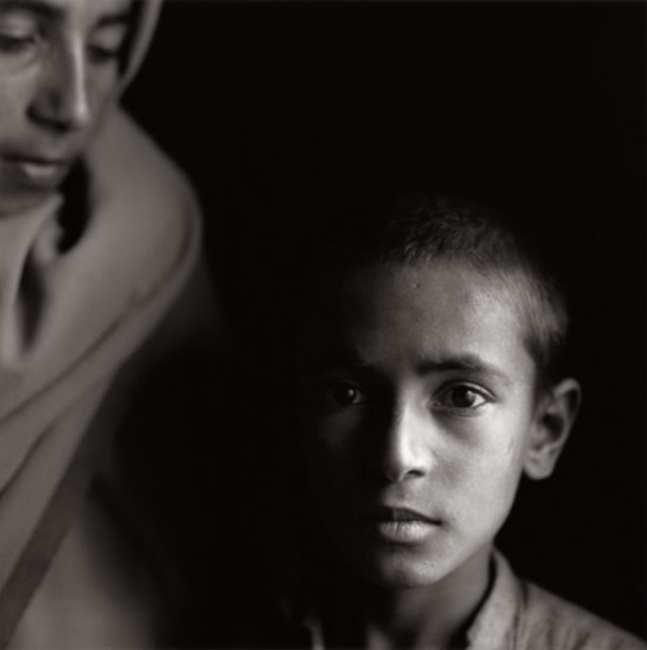

Fazal Sheikh’s photographs aren’t about the Taliban, though. Or about the Soviet occupation, or the destruction of Afghanistan’s cities, or the civil war. They’re about the people who fought, regardless of whom they fought for or against. And they’re about the people too old to fight. And the people who waited at home while their loved ones fought. And the people who fled the fighting. And the children who were born in the aftermath.

Sheikh not only shoots their photographs, he also listens to their stories. He gets his subjects to talk about the village that was gassed by pro-Soviet Afghans, the brother who was killed in a firefight in the week before his wedding, the mother/sister/wife/daughter who was raped or forced to sell herself for food, the son who died during an ambush in some unknown pass on some unknown mountain.

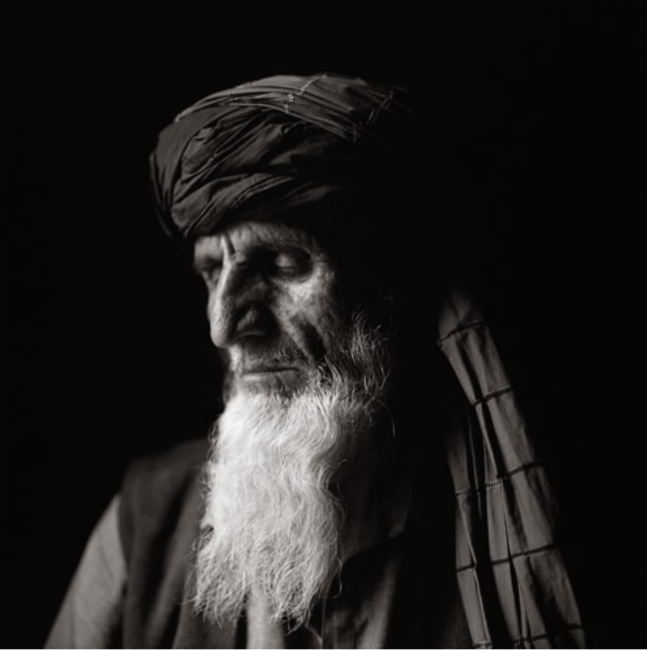

These are faces that have seen too much, endured too much, lost too much. These are faces that are etched with the knowledge that they will see still more, and endure more and lose more. They endured and defeated the great Soviet Army, just as they endured and defeated the great British Army a century before, just as they defeated the Persians before that and the Mongols before that. At the time these photographs were taken, they were enduring the Taliban. Now they’re enduring a NATO occupation and a resurgent Taliban. We can only guess who’ll they have to endure next.

Although the light of the gas lamps which illuminate these faces is soft and glowing, there is very little that is soft in the faces themselves. Even their memories seem to be carved out of granite.

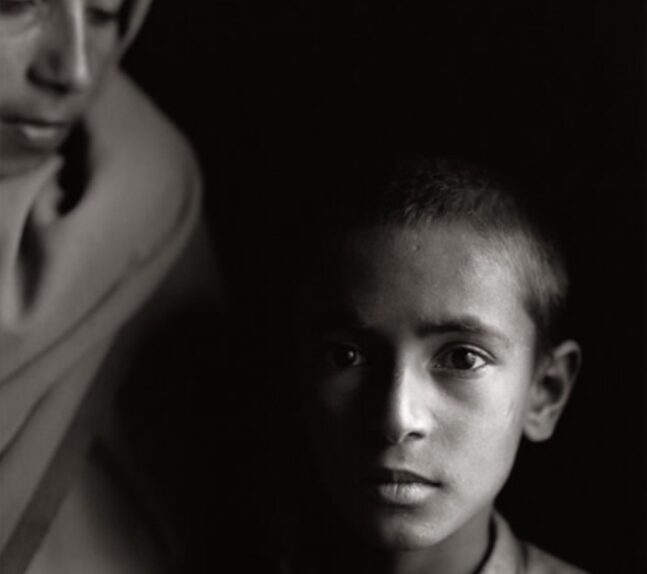

This series, The Victor Weeps, is in many ways a family photo album. If you look at the face of the young boy and his older sister in the photo above, you can also see the faces of every mother, wife, and sister who ever worried about the future of their son, husband, and brother.

But there is also a chance the lives of these people or their children will improve. Perhaps they’ll leave Afghanistan as refugees and find a better life somewhere else. Perhaps they’ll stay in Afghanistan and rebuild their homeland into something stable and prosperous. Perhaps Afghanistan will find some measure of peace in the future.

Sadly, that doesn’t seem likely.