Esther Bubley isn’t a familiar name to most photographers. Nonetheless, she was a quietly revolutionary figure. She wasn’t a revolutionary so much by choice; rather Bubley was a product of her time, and her time was one of radical change for women.

She was born in Wisconsin in 1921, the fourth of five children of Russian Jewish immigrants. While in high school, she became fascinated by the photography in LIFE magazine and the images produced during the Great Depression by the Farm Security Administration. After two years of study at a teachers college in Wisconsin and a year of studying documentary photography at the Minneapolis School of Design, Bubley decided she was ready to be a professional photographer. In 1941, at age twenty, she packed her bags and moved to New York City. She was 20 years old.

This was around the beginning of World War II. In large numbers, men of military age men were either being drafted or enlisting in the military. Professional photography was almost exclusively a male occupation at that time. A lot of those jobs were suddenly vacant. Bubley was soon hired by Vogue to work as an assistant.

But she hadn’t left the Midwest for New York to be an assistant. Less than a year later Bubley was offered a job with the Office of War Information in Washington, DC. Although she was hired to work in the darkroom, she was quickly given small photo assignments–routine work depicting life in the nation’s capitol. Her breakthrough assignment was to record the journey of men who’d recently enlisted as they traveled to their induction centers.

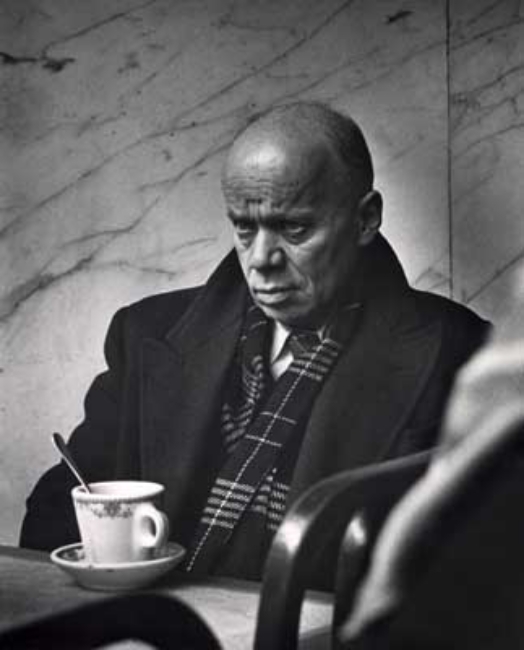

When the OWI closed at the end of the war, Bubley’s male supervisor was hired by the public relations department of Standard Oil of New Jersey. He brought her with him as a photographer. Bubley’s assignments for SONJ were incredibly diverse, involving almost anything that could be remotely related to oil or oil-based products. She documented the lives of oil workers in the town of Tomball, Texas, she photographed paper mills in the Carolinas and onion fields in Massachusetts. In 1947 she traveled much of North America by bus and produced one of her best-known series: Bus Story.

These photographs revealed the new mobility of post-war America. People were moving, social barriers were being shattered, geography no longer limited a person’s opportunities. Although women found themselves temporarily reduced to their pre-war role, they’d tasted some freedom and power and they weren’t ready to give it up. Women traveled unescorted on the bus; something ‘decent’ women wouldn’t have done before the war. Some traveled alone with their children.

Bubley’s work with SONJ attracted enough attention that she was offered a wide variety of industrial trade jobs and photojournalist assignments. Over the next two decades she produced work for Life magazine, for the Ladies Home Journal, for various local newspapers, for UNICEF, for Pepsi-Cola, for Pan American Airways. At the same time, she also continued to travel throughout the world for SONJ. Although she was briefly married, her work and travel schedule interfered. Faced with a choice between a more traditional marriage and her work, Bubley elected to keep working.

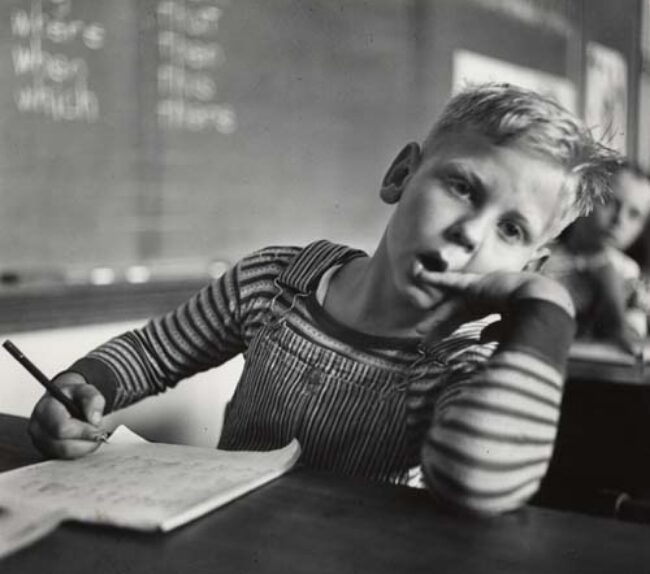

From 1948 to 1960 Bubley published a series of photo articles entitled “How America Lives” for the Ladies Home Journal. These were deeply personal pieces, showing the lives and relationships of ordinary people throughout the US. Farm families, middle class suburbanites, school drop-outs, couples in divorce court, hospital workers. The series was wildly popular, in part because Bubley was able to gain the trust of her subjects and show them in relaxed, intimate situations.

Although she had developed a strong reputation as a photojournalist, Bubley continued to receive assignments that dealt with “women’s issues,” like health care or education or matters dealing with the family. She accepted those assignments, but usually found a way to move them beyond their original parameters. She turned women’s issues into human issues.

Bubley developed a special interest in photographing health care issues. Her ability to gain the subjects trust and disappear into the background (while still getting the critical shots) allowed her to photograph everything from an emergency tracheotomy performed in a hallway to the suffering of the mentally ill.

By the mid-1960s the heyday of photojournalism magazines was in decline. For more than two decades Esther Bubley had lived a life unimagined for women at the time she was born. She’d not only supported herself doing the work she loved, she’d excelled at it. She’d done the work she was assigned to do, but she’d done it in such a way that she broke social and gender barriers. She’d seen her work widely published…in magazines, on magazine covers, even displayed in museums and art galleries and the Library of Congress.

Bubley’s retirement was as unconventional as her working life. Instead of settling in quiet obscurity, she bought a large apartment in mid-town Manhattan where she lived with a beloved (and much-photographed) Dalmatian. In her ‘retirement’ she wrote and published books on gardening. She died in 1998.