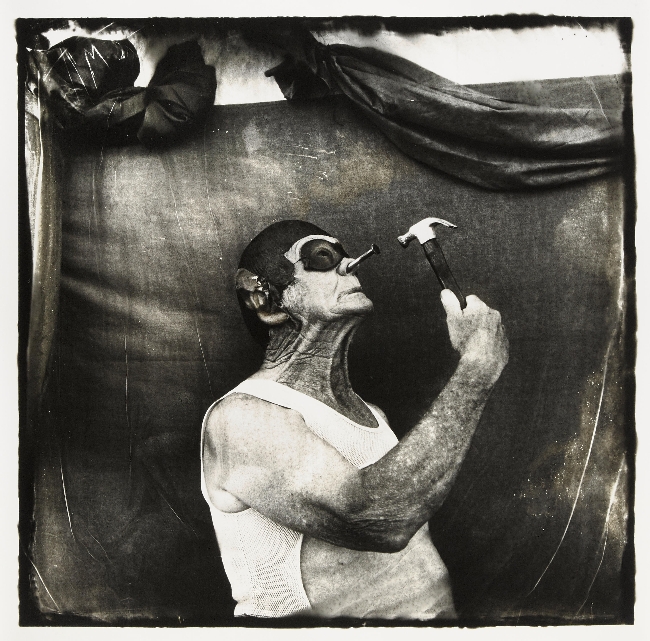

The work of Joel-Peter Witkin is best described as photography of the grotesque. In fact, I’d go so far as to say it can only be described as photography of the grotesque. Everything about his work is grotesque: the subject matter, the models, his printing process, the final image. Witkin’s work is a perfect storm of grotesquery.

He was born in Brooklyn in 1939 (he has a twin brother, Jerome). Their parents divorced when they were quite young because of religious differences (their father was Jewish, their mother Catholic). Their mother raised them in a rather strict religious environment. Three events seem to have shaped Witkin’s artistic interests. The first was a traumatic event.

“We were going to church. While walking down the hallway to the entrance of the building, we heard an incredible crash mixed with screaming and cries for help. The accident involved three cars, all with families in them. Somehow, in the confusion, I was no longer holding my mother’s hand. At the place where I stood at the curb, I could see something rolling from one of the overturned cars. It stopped at the curb where I stood. It was the head of a little girl. I bent down to touch the face, to speak to it – but before I could touch it someone carried me away.”

The second event occurred years later. At some point in the 1950s, Witkin became interested in photography. His brother, studying to be a painter, asked him to take his camera to the Coney Island Freak Show and photograph people with unusual body forms. That apparently sparked Witkin’s interest in physical deformities.

Third, in 1961 Witkins was drafted into the Army. Because of his photographic skill, he was assigned to a photographic unit. He’d apparently hoped to become a combat photographer, but instead served as a public information photographer at Fort Hood, Texas. His job included documenting military training accidents.

After his military service, Witkin worked in a variety of technical and medical photography departments while attending college. In 1976, he received an MFA; the next year he was awarded his first grant from the National Endowment of the Arts.

It was around this time that Witkin began to gain a strange sort of prominence in the photographic art world with a series of images that seemed to revolve around the world of sado-masochism. I say “seemed” because Witkin insists his work is primarily religious. He interprets the voluntary suffering of masochists to the ecstatic suffering of Christ. That view, obviously, distressed a lot of people–including members of Congress, who eventually used Witkin’s work as evidence that funding to the NEA should be cut.

By the mid-1980s Witkin had moved beyond SM-based images into studies of what he calls “the infinite will of God.” By that he meant people whose lives or bodies were outside the norms of society. He placed an advertisement looking for models, particularly seeking:

Pinheads, dwarfs, giants, hunchbacks, pre-op transsexuals, bearded women, people with tails, horns, wings, reversed hands or feet, anyone born without arms, legs, eyes, breast, genitals, ears, nose, lips. All people with unusually large genitals. All manner of extreme visual perversion. Hermaphrodites and teratoids (alive and dead). Anyone bearing the wounds of Christ. Women whose faces are covered with hair or large skin lesions willing to pose in evening gowns. People who live as comic-book heroes, boot, corset and bondage fetishists. Anyone claiming to be God. God.”

And he got responses. Lots of responses. As in the photograph below. The figure looks like a broken mannequin; it is, in fact, a living person whose mother took thalidomide to combat morning sickness. He was born armless, legless, without ears, without eyelids, with a half-formed penis and with half-formed skin. He lives in bandages that have to be regularly moistened. According to Witkin, when this man signed his model release he made the following request: “Whatever you do, Joel, make me look like a real human being.”

The photograph and the request creates all sorts of uncomfortable questions. What makes a person “a real human being?” Did Witkin think he was able to do that? If so, did he succeed? I’m inclined to think that by simply making the request, the man proved his humanness, but I’m not entirely satisfied with my own answer.

Witkin’s work grew more outlandish and macabre when he worked out an arrangement with a hospital in Mexico City. They allowed him free access to the anonymous corpses and body parts delivered to their morgue so he could incorporate them into his art.

With each escalation in his work, Witkin faced an equal escalation in both praise and condemnation. He has been accused of exploitation of his subjects–both the dead and the living. He has been called a sensationalist, a pervert, a degenerate of the first order. He has also been called a genius, an artist, and a photographer whose “restlessness and desire…leads him to places others fear.”

All of those things might be true. As for Witkin, he says “I will be remembered as a Christian artist.”

One thing everybody agrees on is that Witkin is a brilliant, if obsessive, print-maker. He prints the negatives through tissue paper. He’s been known to process his prints using tea or coffee. He’s covered prints with wax, which he heats to create a sort of polish. He scratches the negatives with razor blades, he pokes them with pins. He tortures and abuses and mutilates his work in a way that seems to mirror his subjects.

And he works slowly. Very slowly. Incredibly slowly. Witkin produces about 10 new prints a year.

Aside from his printing process, I don’t see any indication that Witkin’s work has evolved over the last thirty years. His subject matter may have gotten more extreme, but he’s still producing essentially the same type of photographs.

Although Witkin is no longer the star of the bleeding edge of art photography, his work still sells for thousands of dollars. It’s still sought-after by collectors and is displayed in museums throughout the world.

In the end, a meticulously printed still life photograph with a severed head and a plate of fruit has to work as a still life photograph. What draws the attention to Witkin’s work is not the still life; it’s the severed head. It’s not the quality of the light, it’s not the composition, it’s not the brilliantly-produced print; it’s the severed head.

Maybe genius doesn’t have to evolve. Maybe that sort of monomaniacal obsession is a significant facet of his peculiar genius. I don’t know. What I *do* know is that for me his work never quite progresses very far beyond the severed head.