He has been called “the hottest war photographer on the contemporary scene.” He’s been accused of ‘war porn.’ He’s been the subject of an Academy Award-nominated documentary film. He’s won the the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award, the World Press Photo award (twice), the Leica Award (twice), the International Center of Photography Infinity Award (three times), the Robert Capa Gold Medal (five times), the Magazine Photographer of the Year (six times), as well as a Heinz Foundation award and the TED Prize.

He’s photographed conflicts in Northern Ireland, Afghanistan, Haiti, Somalia, Iraq, Rwanda, Bosnia, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka, Chechnya, Indonesia, the West Bank, Kosovo, Zaire. He was in lower Manhattan on 9/11/2001 and photographed the destruction of the twin towers. He’s photographed combat and the results of combat. He’s photographed famines in Africa, prison inmates in the U.S., heroin addicts in Pakistan. He’s been wounded in combat on at least two occasions. He’s put down his camera to rescue people from lynch mobs and to transport famine victims to feeding stations.

He has a personal/political/social agenda and isn’t shy about announcing it. At the same time, he acknowledges his agenda is ridiculous. It’s a simple agenda: “…to put an end to a form of human behavior which has existed throughout history by means of photography.”

His name is James Nachtwey.

Nachtwey was born in 1948 in Syracuse, New York. He attended college in the late 1960s–an era of political radicalism in the U.S., the era of the civil rights movement, the era of the Vietnam. He studied Art History and Political Science in college. After college he drove a truck and worked in the merchant marines. During this period he decided that what he really wanted to do with his life was to take photographs for a newspaper.

He taught himself photography and in 1976, at the age of 28, he persuaded a newspaper in New Mexico to hire him. He spent the next four years refining his skills. In 1980, when he was 32 years old, he packed his bags and moved to New York City to become a freelance news photographer. He managed to quickly score an overseas assignment for the Black Star agency: the events surrounding the 1981 hunger strike by imprisoned IRA soldiers in Northern Ireland. Nachtwey has been photographing conflict almost steadily ever since.

Why war? According to Nachtwey,

“…to show [the public], to reach out and grab them and make them stop what they are doing and pay attention to what is going on – to create pictures powerful enough to overcome the diluting effects of the mass media and shake people out of their indifference – to protest and by the strength of that protest to make others protest.”

All successful war photographers eventually face the charge of engaging in ‘war pornography,’ of taking lovely photographs of horrible things. The result, many claim, is that the horrible thing becomes romanticized. Nachtway has been accused, more than once, of being in love with war. This is the paradox inherent in war photography: how does one take a compelling photograph, one that catches the eye and holds it, without feeding what has been called “the sordid appetite for horror”?

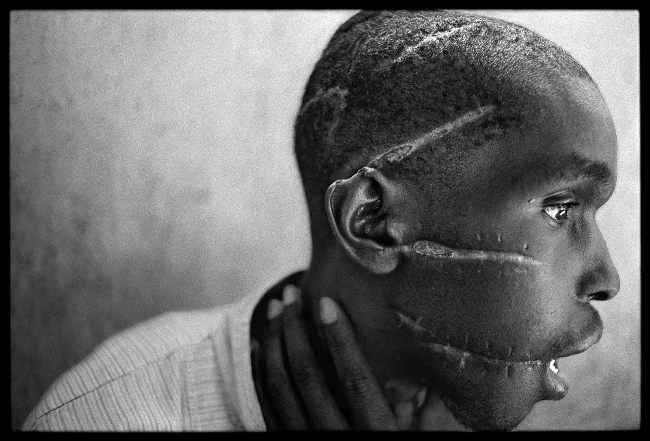

Nachtwey understands that war photography has sparked an aestheticization of war. War images become an expression of art. He knows that by reducing conflict and combat into a still frame war photographers can actually insulate the viewer from the reality of what’s depicted inside the frame. One way he attempts to avoid that is to show the result of conflict as well as the conflict itself. It’s possible, for example, to see the photograph above of the young Palestinian as celebratory of violence and chaos. It can be seen as a romantic image. War porn. There is no way, however, to see the following image of a survivor of a machete attack as romantic or celebratory.

During the Rwandan genocide in 1994, hundreds of thousands of Tutsi tribesmen were murdered by the Hutu majority. The man in the photograph above, however, is not a Tutsi; he is, in fact, a Hutu who objected to the massacre. He was placed in a death camp and given the same treatment as the Tutsis. The image is powerful on its own, but significantly more meaningful when coupled with the man’s narrative.

And therein lies another of the problems with war photography. The vast majority of photographs are seen by the public without any context. One image on the front page that editors hope will encourage the readers to read the accompanying article. Selecting that one photograph involves a lot of decisions, including the decision of just how much the paying public is willing to look at.

The reality is conflict and natural disaster photography is a form of photojournalism, and in capitalist societies photojournalism exists to sell newspapers and news magazines. Sensationalism and spectacle draws readers and viewers. The conundrum Nachtwey faces is how to further his stated agenda of stopping war and relieving suffering while still reaching the public. He understands that in order to reach the public, he has to create images that will appeal to editors as well as to ordinary people. Nachtwey tries to do that by showing the ordinary people who suffer.

In September of 2001, Nachtwey and six other photojournalists created their own photo agency: VII (the agency’s name refers to the seven founding photographers). They wanted more control over their photos, more control over their assignments, and an open admission of their agenda. According to their mission statement, “What unites VII’s work is a sense that, in the act of communication at the very least, all is not lost; the seeds of hope and resolution inform even the darkest records of inhumanity; reparation is always possible; despair is never absolute.”

The day after VII’s formation in Paris, Nachtwey returned to his New York City apartment (located in the South Street Seaport in lower Manhattan). The following morning, terrorists crashed commercial jetliners into the World Trade Center–a ten-minute walk from Nachtwey’s apartment. He heard the initial crash and, after taking a few photos from his rooftop, gathered his equipment and went to the scene.

Nachtwey was standing on the street next to the North Tower when it collapsed. He ran into the lobby of the Millennium Hotel across the street and luckily spotted an open elevator. Moments later the falling debris devastated the hotel’s lobby. Nachtwey survived only by moments. Despite that narrow escape he spent the next ten days, up to 20 hours a day, photographing the tragedy taking place in his own neighborhood. His photographs, the first photos take for the new agency, were featured throughout the world.

Perhaps the most important lesson Nachtwey learned was one of the earliest lessons from the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland.

“All the violence in Belfast was happening right inside residential neighborhoods. And that’s what I’ve seen ever since. Wars are no longer fought on isolated battlefields.”

I suspect–I hope–that during those ten days Nachtwey found some reassurance in his new agency’s mission: “…in the act of communication at the very least, all is not lost; the seeds of hope and resolution inform even the darkest records of inhumanity; reparation is always possible; despair is never absolute.”