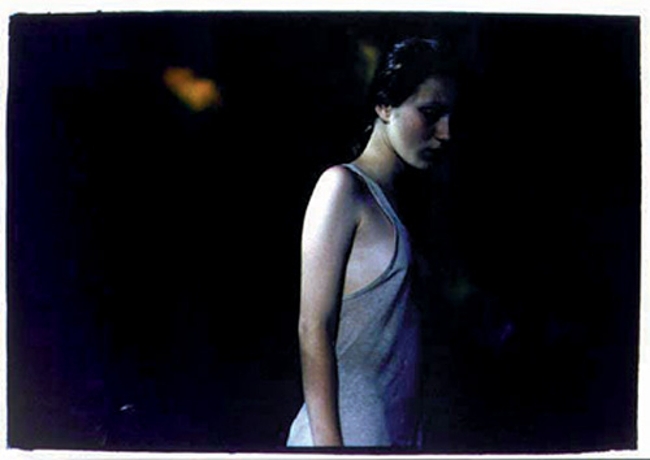

For the last quarter of a century photographer Bill Henson has been taking strangely dystopian photographs of urban industrial landscapes and dark, melancholy semi-candid portraits of alienated, disaffected adolescents and teens. His work has a distinctly cinematic quality. While Henson is fairly well-known in his native Australia and through much of Europe, his work has received relatively little attention in the U.S.

For much of his career Henson has focused his camera on teens and adolescents. He often photographs them nude–or nearly nude–and in settings that are rather lurid. His subjects are often depicted in poses that are sexually suggestive or engaged in other behaviors upon which society frowns.

Many of his critics question whether Henson is simply acknowledging the reality of the lives of some feral, cast-aside kids or whether he is glorifying that sort of life. There’s no denying that Henson’s technique creates rich, soft-edged, sumptuous images and that those images have a sinister/romantic/sensual aura to them. The question, I suppose, is whether or not that romanticism is inherent in the situation or a product of Henson’s style.

Henson’s detractors have labeled his work ‘iconographic nonsense’ and say that calling it art “justifies a vulgar relish in depicting naked, pouting youngsters.” They say his photographs exist “uncomfortably between the sinister and the trivial.” He has been accused of having a sort of stalker aesthetic and having a perverse interest in the debasement of women–specifically young women, and even more specifically, those who are passing through that indeterminate border area between girlhood and womanhood.

Henson admits to being fascinated with adolescence. He calls it “that sort of highly ambiguous and uncertain period where you have an exponential growth of experience and knowledge, but also a kind of tenuous grasp on the certainties of adult life.” He cites the etymology of adolescent, which indicates a lesser form of adult–a sort of nascent adult–as an indication of the essential weirdness of that phase of life. Instead of being adult, adolescents try on some of the various roles of adulthood (or their interpretation of those roles.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Henson’s images is the way all the aspects of photography coalesce. The technical aspects (choice of lenses, lighting, film, etc.) enhance and emphasize the artistic and emotional aspects. He tends to use long lenses and shoots his subjects from a distance, which magnifies the voyeuristic feel of the images. The viewer feels almost as if we’re spying on private moments, moments in which the subjects are exploring their own personal limits.

Shooting the photographs at dusk or in the early evening means a strong directional light is needed to illuminate the subjects. The result is the loss of some detail and an exaggeration of other details. That creates ambiguity and obscurity; the darkness of the images is as emotional as it is photographic.

Henson also shoots exclusively on film because he feels it has potential for far greater extremes in lighting situations. He also likes the fact that “negative film is designed to be half the process, the second half being the making of the print.” My sense–and I should admit I’m basing this not on anything Henson has said specifically, but on the totality of my reading–is that film itself plays a significant role in his creative process. It’s as if the physical reality of having to deal with a negative gives him an interim step, and that extra forces him to slow down and consider how he wants the final product to look.

Henson’s work is intended to be contradictory–and perhaps controversial. He creates beautiful images of scenes that often have ugly connotations. He turns the viewer into a voyeur (and it’s no coincidence that both terms–viewer and voyeur–come from the French term voir). The result can be titillating, it can be offensive, it can be romantic, it can be alarming, it can cover the full range of emotions. But his work is designed to makes one experience a range of emotional responses. Even if that response is to withdraw, to feel disconnected or dissociated, then it has to be considered effective.

I admit that I’m a wee bit uncomfortable with Henson’s work. Not with the photographs themselves, but with his choice of subjects. There’s no denying the beauty of his work, but it’s entirely reasonable to be concerned about the balance between an adolescent’s ability to make decisions about his/her life and the awareness of the consequences of those decisions.