NUDES NUDES NUDES

A week ago, on 6 May 2007, approximately eighteen thousand men and women of various ages showed up in the Zócalo, Mexico City’s principal square, just before dawn. At a signal, they took off all their clothes. Another signal, they all saluted. Another signal, they all curled up in a fetal position. On a nearby rooftop, directing that Busby Berkley sea of nude people, was a 40 year old American photographer.

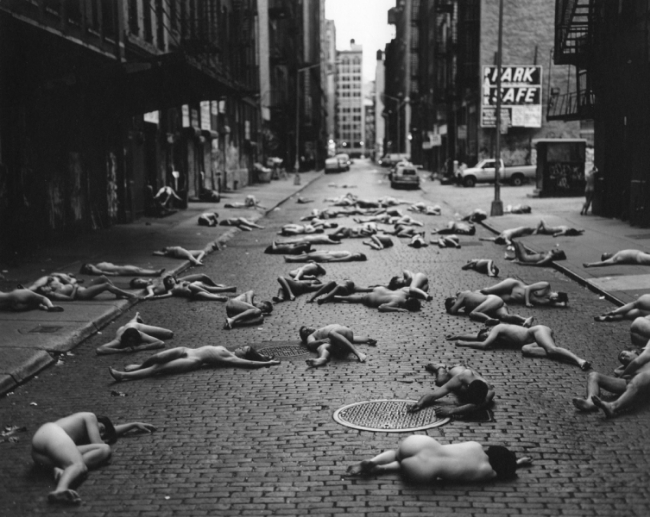

Spencer Tunick has made a career of photographing nudes. His take on the nude is unlike that of most photographers. Tunick doesn’t seem particularly interested in the individual human body. He’s not even particularly interested the human body as an aesthetic form. For him–especially in more recent years–the individual human body serves only as a compositional element, a form to be shaped or placed within the frame, a single blob of paint on a grand canvas.

Tunick is interested in bodies en masse.

How did Spencer Tunick come to photograph 18,000 nude people in Mexico City? Not surprisingly, he started out small. He shot his first nude in 1986; a woman–one woman–standing at a bus stop. He seemed to be intrigued by the conjunction of the nude body in an unexpected setting, and for the next eight years he continued in that vein. Sometimes he used one subject, sometimes two, rarely three. By placing nude bodies in locations where nudity wasn’t usually expected, Tunick was making a statement about the social construction of nakedness. Society arbitrarily determines the locations where it is acceptable to be without clothing. Tunick’s early nude photographs are (in my opinion) more intellectually intriguing than visually interesting.

That practice changed in 1994, when Tunick photographed nude bodies piled up outside the United Nations building in New York City. The photograph, he said, was a response to the genocide in Rwanda.

As a political statement, the photographs outside the UN weren’t particularly effective. But the event sparked a new idea. Tunick decided he wanted to create “flesh sculptures,” pieces that were as much about performance as they were about photography. He began to call his work “installations” rather than photographs.

As his work garnered more attention, Tunick began to get more volunteers for his flesh sculpture installations. He went from photographing a couple dozen models to arranging installations involving fifty, or a hundred, or two hundred. Then 1,700 volunteers showed up in Newcastle. And 2,500 stripped down in Montreal. 4,000 in Chile, 4,500 in Melbourne, 7,000 in Barcelona. And, again, last week in Mexico City he found himself looking down on at least 18,000 volunteers.

He organizes the people by their physical characteristics. Obviously, he pays attention to skin color (he uses a seven point scale), but he might also categorize them by hair length or body shape or gender. He gives the volunteers few explicit instructions. No clothes, of course, and no socks, shoes or hats. He instructs them to “Be nice and pay attention, be friendly with your neighbors.” He discourages them from drinking or taking drugs.

As the crowds of nude volunteers have grown, so have the logistical problems involved. Tunick generally shoots his installations very early in the mornings. His subjects often have to arrive on the scene between 3:00 and 4:00 AM in order to be ready at first light. The hour is chosen partly for the early morning light, partly to avoid disruption of the traffic in the host city, and partly because the hour discourages trouble-makers (and, of course, it’s easier to insure his subjects are sober and manageable).

When so many nude bodies are sprawled over the landscape they cease to be perceived as nude bodies. They become an abstract element of an art installation that’s based on the land itself. In a way, Tunick treats his nude volunteers in the same way Christo uses fabric; they’re used to temporarily transform the environment from its normal reality into something strange and exotic. Although the effect would be different, the principle would be same if Tunick substituted various flowers for the naked bodies. Or cakes. Or office supplies. The difference, of course, is that people are easier to manipulate and much more fun, as well as being a tad shocking.

Here’s the most interesting thing about Tunick’s work. The photographs he makes isn’t really the art; it’s just the record of the art. The art itself is the event. And in a way, Tunick is still doing what he’d originally set out to do: he’s exploring the social construction of nakedness. He has, in effect, taken the nakedness out of nudity. There is nothing sexual about his photographs, nothing erotic, nothing lascivious. The sensuality–if it exists at all–is the sensuality of the setting, not the sensuality of the body.

Spencer Tunick’s next flesh sculpture installation will take place on 3 June of this year in Amsterdam. He’s still accepting volunteers; the deadline for volunteering is 25 May. Volunteers are rewarded with a gift–a print of the installation. The actual location of the shoot will only be revealed to the volunteers at the last minute.

If you’re interested in volunteering, go to www.spencertunick.com/. And be sure to report back to us about the experience.