In 1945, detective novelist Raymond Chandler wrote an essay about the ‘new detective story.’ The stories were considered new because they introduced a new type of protagonist: the hard-boiled detective. In part, Chandler wrote:

“…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid…. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor, by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it…. He is a common man or he could not go among common people. He has a sense of character, or he would not know his job…. The story is his adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. He has a range of awareness that startles you, but it belongs to him by right, because it belongs to the world he lives in.”

I thought of that passage when I first saw the work of Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama. If photographers can be hard-boiled (and I think there is little doubt about that), then Moriyama deserves that description. He was born in 1938, during the Second World War. Like Shomei Tomatsu, Moriyama lived in post-war Japan. Unlike Tomatsu, however, Moriyama had never known pre-war Japan. Moriyama grew up during the U.S. occupation of Japan. He’d never experienced a nation that wasn’t devastated economically, militarily, culturally, and spiritually.

By 1961, when Moriyama was 21, Japan’s economy had turned completely around; the nation was becoming an economic success. However, there remained an underlying sense of profound shame among older Japanese. They had lost the war and their emperor had been forced to renounce his divine status. Among many younger Japanese, there was a sense of rootlessness, of deep alienation. In Moriyama that feeling was exacerbated by a failed romance. He left his home in Osaka and moved to Tokyo. He sought work as a graphic designer, but ended up taking a position as an assistant to photographer Eikoh Hosoe. Moriyama quickly took up the camera on his own.

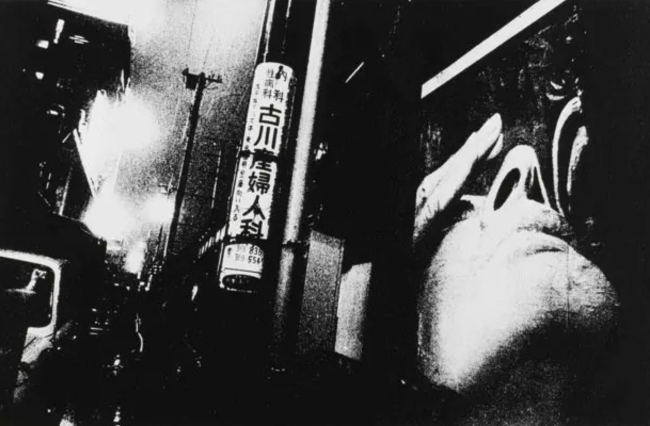

Moriyama became a denizen of the Shinjuku Ward of Tokyo, one of the liveliest areas of the city. Not only does it have the city’s busiest train station, it also has the highest ratio of foreign nationals residing in Japan. Moriyama spent most of his time in the Golden Gai and Kabukichō districts of Shinjuku–areas known for their bars, brothels, nightclubs, restaurants, coffee shops, movie theaters, and street life. Moriyama has called the theaters, with their movies and newsreels, “a second school.”

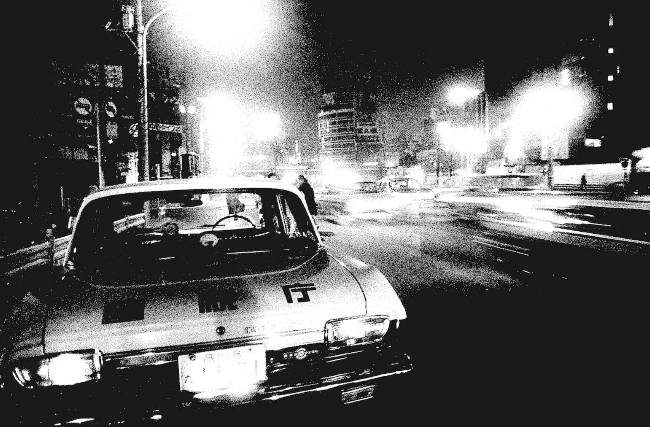

He soon developed his own style of photography. Moriyama restlessly prowled the streets, usually alone, shooting a lot of film, photographing scenes that he hoped would “express the realness of Japan.” Because the streets of Shinjuku were busy, his photographs were busy. Shot from the hip, frequently blurry, the photographs have an agitated feel to them–a sense of too little sleep, too much coffee, too much alcohol, too many cigarettes.

It was during this period that Moriyama shot what would become his signature photograph. He had been staying in a hotel near a U.S. military base in Misawa. As he left the hotel he encountered a scruffy stray dog. At the time it seemed nothing special.

“In the morning, as soon as I walked out of the hotel, I saw a dog and I took the picture. I never thought it would be famous.”

In many ways, this photograph was pitch perfect to become iconic both of Moriyama himself and of his generation. The photo shares a title with a film by noted Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. The 1949 movie Stray Dog tells the story of a police detective whose pistol is stolen while he is riding on a crowded bus, and of his attempts to retrieve the weapon and remove the shame of having had it taken from him. The movie can be seen as a metaphor for a humiliated, occupied post-war Japan in which desperate people commit desperate acts that would have once been seen as immoral or unthinkable even by the offenders. Under the existing circumstances, however, conventional morality no longer seemed to apply.

Like the villain in the Kurosawa film, the stray dog in Moriyama’s photograph had adapted to existing circumstances. The dog glances at the photographer and gives a warning half-snarl. It’s a rough, slouching beast, on its own, alert and wary, and it means to take care of itself in any way it can. This is nobody’s pet. This is a hard-boiled dog, living in a world he didn’t shape, under circumstances over which he has no control, and he’s dealing with the world exactly as it is, not flinching away from the reality of it–and he’s getting by.

That’s not unlike the way Moriyama approaches photography. He roams the streets, solitary, always alert, always moving, scavenging what he can find, coolly appraising what’s around him, taking the world as it is. And for him, the world is fragmented, semi-chaotic, harsh, unforgiving and very, very real.

Moriyama shoots almost exclusively with Kodak Tri-X film. It’s a reliable high ISO black and white film. His early work was extremely grainy and printed in high contrast. The result is an image that is realistic without being real.

“Monochrome is stimulating and is very erotic. Sometimes my heart is beating fast when I see a black and white world in the developer…. I have decided to keep using Tri-X until it’s discontinued.”

Moriyama has called the camera “a machine that copies reality.” He often seems to be drawing a distinction between realism and reality. He understands that he cannot show reality; he can only show something that has the feeling of being real.

“No matter how many pictures I take, I can never capture the vast number of fragments of the world that cross with the irreplaceable moments of my life.”

Moriyama is often associated with an experimental 1968 Japanese photo magazine, Provoke. Although only three issues of Provoke were issued, the style of the magazine has been massively influential–not just on Japanese photography, but on street photography worldwide. The style is generally referred to as are, bure, bokeh, which approximately translates as ‘rough, blurry, narrowly focused (or out of focus)’. It’s more a metaphor for the style of shooting than a description of the finished image.

Over the last twenty years, Moriyama has begun to soften his style. He still shoots with small, simple, handheld cameras, he still shoots Tri-X, and he still prowls the streets of Shinjuku. His photographs still retain the feeling that something has just happened, or that something is just about to happen. But his prints are smoother, less confrontational, more crisp.

After four decades of shooting photographs, Daido Moriyama remains the stray dog. His work might be somewhat softer, but he remains completely hard-boiled. I’m going to repeat part of the quotation by Chandler here, because it applies so perfectly:

…down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean.

There’s nothing mean in Daido Moriyama’s work, though it sometimes depicts mean circumstances. In essence, Moriyama’s work is more akin to a conversation between the photographer, the camera, and the streets. There’s no sense of judgment, no sense of instruction or warning or moralizing. There’s simply what’s there, when it’s there, take it or leave it.