NUDES NUDES NUDES

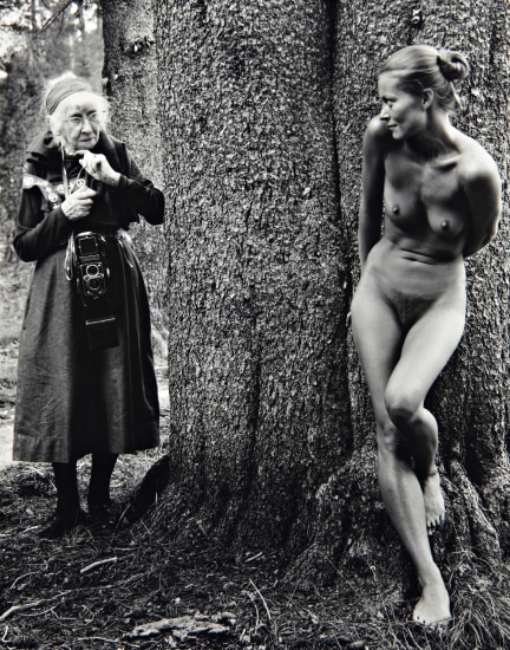

When I was young–maybe fifteen years old–I saw a photograph in a magazine that left me gob-smacked. A prim-looking old woman in a long black dress, a twin-lens reflex camera around her neck, standing in the woods. Peeking coyly around a tree, an exotic-looking nude woman. The old woman appears a tad startled and is giving the young one a look that seems vaguely disapproving.

I’d seen powerful photographs before, but they were always news photos. I’d never experienced a photograph in quite that way before. There was something about the juxtaposition of the two women, their interaction, the way they looked at each other that engaged me immediately. All those wonderful contradictions; age and youth, nudity and frumpishness, straight-laced and impishness, beauty and…well, and another sort of beauty. Because even to a fifteen year old boy it was pretty clear that both women were beautiful in their own way.

I’ve no idea the name of the magazine in which I saw the photograph. I don’t recall where I was when I saw it. I didn’t really know anything about photography back then. I had no idea who the photographer was. I didn’t really care. All I knew was that seeing the photograph completely changed my understanding of photography.

Years later I discovered the photographer was Judy Dater. The two subjects were a young model/writer with the improbable name of Twinka Thiebaud and one of the masters of portraiture, 91 year old Imogen Cunningham.

Oddly enough, that image–which has become Dater’s signature photograph, the one with which she will forever be identified–grew out of another image. As a young girl she had stumbled on a book of paintings by Thomas Hart Benton. One painting, Persephone, had a profound influence on her.

“The part of it that never left me was the subject, this wrinkled up old geezer looking at this gorgeous, young woman naked and not knowing she was being looked at.”

Over the years Dater made a lot of photographs with that theme–a nude person being looked at by a clothed person. “I kept trying it over and over again and it finally kind of came together.”

That photograph of Imogen and Twinka was a product of its time, a period in which the second wave of feminism was taking root. Instead of a man secretly leering at a nude woman, it depicted two women openly looking at each other. It removed the sexual dynamic and replaced it with a more evaluative ambience. No man lusting after the woman, but two women–one perhaps seeing her past, the other blithely innocent of her future.

Like that photograph, Judy Dater is also a product of her time, a product of–and a participant in–second wave feminism. She was born in Hollywood in 1941, and attended college as an art student primarily interested in drawing. When she was a senior, she decided to take a photography course. It was a transformative decision in many ways. Dater, who had married young as so many women did in that era, had an affair with her instructor Jack Welpott, who was nearly twenty years her senior. She eventually divorced her husband, married Welpott, and became a photographer.

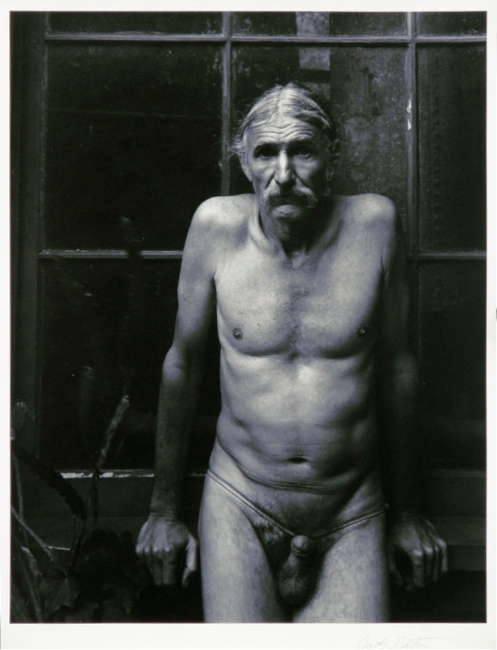

Dater’s early career seems to have been influenced as much by chance meetings as by design. In 1964, just a few years after taking that first photography class, 23 year old Judy Dater attended a conference at Big Sur on the work of Edward Weston. Also in attendance was a woman in her 80s, a woman who had made a name for herself–and scandalized polite society–by photographing male nudes at a time when ‘nice’ women just didn’t do that. Imogen Cunningham.

Cunningham wanted to photograph Dater. The two women, despite the contrast in their ages, became friends. Dater began to focus her photography on portraiture, frequently nude portraiture. During the 1970s she developed an international reputation for her nude work. Using large format cameras and a very deliberate process, Dater photographed nudes with directness. At that time nude women were generally portrayed in two ways: in an “artistic” manner in which the model was portrayed as innocently unaware of or uninterested in her nudity or in a “sexy” manner in which the model was coy and flirtatious. Dater’s nudes, in contrast, were almost confrontational…as if the model was saying “Yeah, I’m nude…so what?”

By the early 1980s, however, Dater’s photography began to lose its sense of direction. Cunningham had died, Dater had divorced her one-time teacher and collaborator (apparently because of his many infidelities), and she seemed anchorless. She turned to self-portraiture.

There is something almost schizophreniform about her work in this period. Although it was clearly informed by the feminism of the time, her work tended to fall into two broad categories. Some of it took a mystical-mythos shape. She photographed herself nude in natural surroundings, suggesting a sort of women-centered symbiotic relationship with the landscape. These weren’t photographs in the popular ‘earth-mother’ vein of nurturing, but instead depicted something more of sympathetic relationship between womenkind and nature–what one felt, the other felt.

At the same time, Dater was creating political self-portraits depicting the confused social conditions of women in capitalist societies. The photographs, with titles like Death by Ironing or Ms. Cling Free, are an attempt to examine the intersection of domesticity, male-oriented sexuality, and commerce that exemplified the status of Western women.

Both the nude-landscape self-portraits and the social issue self-portraits had a very self-consciously didactic feel. Dater was, it seems, more interested in making a personal political statement than in making art. While critics found the work intriguing and generally agreed with the statement(s) she was making, few people were moved by it.

In recent years, Dater has attempted a number of different forms and styles of photography–computer-manipulated collages, portraits of statues, constructed symbolic portraits. Sadly, none of it has garnered much enthusiasm. Her most successful modern work was a series of portraits of ordinary working people in Italy, taken in the style of August Sander. While it’s appealing work, it hasn’t proven very memorable.

Because of her work in the 1970s and 80s, Dater has secured herself a place in photographic history. In a way, her story could be seen as a cautionary tale. When her work was simple, direct, unpretentious, it was powerful. When she turned her talent to serve a goal–even if the goal was laudable and important–the work lost some of its vigor.

Judy Dater is still taking photographs, is still well-respected, is still working–and is still trying to recapture the effortless, emotionally charged, lyrical style she had three decades ago. Nobody will be surprised if she does it. After all, she’s only in her mid-60s; Imogen Cunningham was still shooting photographs when she was in her 90s.

There’s still time.