I was prepared to like Gregory Crewdson before I ever saw his work. Why? Because I read an article in which he described his photographs as “images without narratives.” I’ve always been of the opinion that a single photograph cannot tell a story; it can only suggest one. Crewdson apparently holds a similar point of view. His carefully staged photographs reveal a moment in a story that’s already well underway. To look at a Crewdson photograph is like walking into a room and interrupting an uncomfortable conversation.

Crewdson was born in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn in 1962. His first flirtation with a sort of fame came during his teen-age years, when he was a member of a New York punk rock group called The Speedies. They were briefly (but wildly) popular in the New York club scene during the mid-1970s, a fact that wouldn’t be worth mentioning except for this curious incident: in 2005 Hewlett Packard used a song written and recorded by The Speedies to sell digital cameras. The song was entitled Let Me Take Your Foto.

Crewdson’s interest in photography took a serious turn when he was an undergraduate at SUNY Purchase. As a student, he managed to get an internship at a Manhattan art gallery and later wangled his way into a paid internship at Aperture magazine. He matriculated to the MFA program at Yale. His master’s thesis revolved around a series of photographs shot through open windows into unpeopled rooms, as though the people had just walked out.

In the years since he graduated from Yale, Crewdson’s aesthetic has been refined but remains essentially unchanged.

All of Crewdson’s photographs are gravid with tension, the source of which is readily apparent but whose meaning is ambiguous at best. His earliest professional series, Natural Wonder, was shot in black and white and featured wildlife engaged in peculiar behaviors. Birds, having cleared a circle in the grass, line it with speckled eggs over which they stand alert and on guard. A knot of butterflies surround something unseen in the back yard of a typical suburban home.

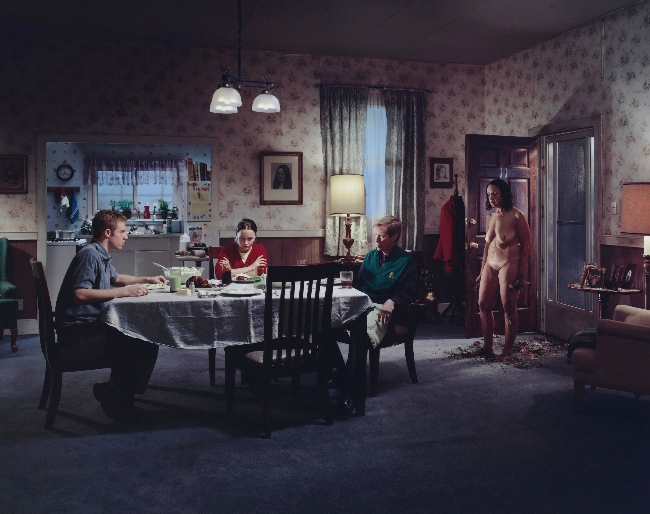

The blandness of suburbia and/or small town America is a common element of Crewdson’s work. He seems fascinated by the notion of anxiety breaking out of the insipid surface of ordinary life. His work often feels like a Norman Rockwell scene staged by Alfred Hitchcock. Family Dinner, shown above, is a perfect example. Something very peculiar and unseemly has interrupted the evening meal.

Crewdson doesn’t explain what’s going on in the photograph. He simply arranges the elements of the scene and lets the viewer arrive at an individual conclusion. The closer one observes the image, the more clues are revealed–but no answers are given. Initially, we are struck primarily by the incongruity of the scene, a naked woman standing in the doorway while the family is gathered around the dinner table. A quick glance at the people at the table reveals a father and the traditional two children, leading us to assume the woman at the door is the wife/mother. The two kids look down, uncomfortable; the father leans forward, full of tension, though it’s difficult to say whether he’s feeling exasperated, worried, or something altogether different.

But there’s more. We notice the table has been set, including a place for the mother. But her chair has been pushed back, suggesting she was sitting at the table with her family a short time before. The plates are empty, indicating the meal hasn’t yet started. The creases of the tablecloth indicate it has been stored away and recently put in place on the table. Around the naked woman’s feet is a scattering of dirt and dead leaves. The clues all suggest she left the table, went outside, removed her clothes, perhaps dug in the dirt, and returned. The viewer is left with questions: what’s happened, why did it happen, and more importantly, what’s going to happen now.

A similar situation is suggested in Bed of Roses, supported by a similar trail of clues. The viewer gets an overall sense of emotional desolation at the first glance. A woman, forlorn and despondent, dressed in her nightclothes, sits alone on the edge of her bed. With each subsequent look, more of the implied story is revealed. What first might appear to be a seductive trail of rose blossoms leading to the bedroom (one thinks “ahh, a romantic evening gone astray“) is gradually revealed to be something more disturbing. The path of blossoms also contains dirt and leaves, and then we notice an uprooted rose bush lying in the bed, its naked roots stark against the sheets. The woman’s arms and legs are scratched, she holds a tangle of roots in her hands. A negligee is slung carelessly over the arm of a nearby chair. Pill bottles stand on the bedside table. The bathroom light is on in the background.

This is both the genius and, in my opinion, the weakness of Gregory Crewdson. To imply a dark narrative through the use of carefully arranged, suggestive clues is brilliant. But Crewdson, once he gets started, doesn’t seem able to stop planting clues. Almost every corner of the photograph seems to contain something meaningful–or potentially meaningful. Every flat surface holds another clue. Every mirror reveals something hidden-but-not-hidden. It’s not enough to suggest melancholy; Crewdson must plant some pharmaceutical anti-depressants, and if that’s not enough he’ll add an overflowing ashtray, and just to be sure we get it he’ll add a clock revealing the time to be just a few minutes before midnight (details not always visible in the small-sized photographs seen here). With that lack of restraint, Crewdson risks turning his photographs into puzzles to be solved instead of images to be appreciated.

When Crewdson takes his camera outside, leaving behind the cramped confines of his interior scenes, his work feels less congested. The images remain unrelentingly bleak, of course, but he is apparently freed of the need to pack information into every square inch of the frame.

Like almost all of Crewdson’s photographs, his exterior work depicts the moments after some unexplained tipping point. The dramatic moment has already happened and people are left to deal with the awkward and discomfiting consequences. As always, it takes a second and third look for the full import of the scene to coalesce. We see a small town at the first blush of dawn, the morning mist hasn’t yet burned off the quiet, nearly empty street. A car has stopped in the intersection, the driver’s door remains open, illuminating the interior. Somebody–a woman, it seem–is still sitting in the passenger seat. The driver is nowhere to be seen.

Unlike his interior work, the viewer doesn’t feel compelled to frantically search the frame for clues. Whatever has happened here feels more organic. Instead of finding ourselves inside a puzzle, we find ourselves peeking in on a painfully private moment–or at least a moment that should have taken place in private.

There is a simplicity to these outside shots that belie the astonishing amount of work that goes into them. As his work gained critical attention and began to command higher prices, Crewdson’s work process became increasingly elaborate. He now stages his scenes in much the same way as a movie director stages a film set. He engages a crew of between 20 and 60 technical assistants; lighting experts, make-up artists, grips, prop organizers. He has even begun using a “camera operator” to click the shutter of his 8×10 camera at the critical moment. These technical assistants are in addition to the actors he hires as subjects and the local residents he uses for logistical support. For example, to obtain the proper level of ‘mist’ in a shot, Crewdson will hire a local volunteer fire department and rent one of their fire trucks to spray fog on the street. Each of his shoots costs tens of thousands of dollars to create (made possible by the fact that each of the massive prints will sell for tens of thousands of dollars).

Given the cinematic process and the movie-still feel of his work, it’s not surprising to learn that Crewdson counts film directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch as inspirations. He has often stated, however, that he feels little desire to actually direct a movie. In one interview he said, “I’m interested in the limitations of a photograph in terms of its narrative capacity to have an image that’s frozen in time, and there’s no before or after.” He perceives that limitation as a strength of still photography.

Crewdson isn’t interested in the story, only in a particular moment of a story. He’s not concerned with the dramatic moment, only with the awkward aftermath of that moment. He’s as indifferent to the resolution of the situation as he is with whatever sparked the situation. His work exists almost exclusively in that singular pause that comes between the instant when something has happened and the realization that something must be done about it. It’s that moment just before releasing the sigh of inevitability.

It’s beautiful work. But I rather think it’s best taken in small doses. That exquisitely painful moment ceases to be either exquisite or painful when seen in one image after the other. One begins to wish Crewdson can find another emotion to explore, or perhaps another way to explore it. There is undeniable beauty in balancing on an emotional pinhead, but one can only remain there for so long until the balancing act grow stale.

And yet, looking at the man in the suit, standing in the rain, holding a sheet of paper in his hand, his car not so much parked as abandoned near the curb, his briefcase on the street–looking at that image, it’s difficult not to feel something. It’s difficult not to hope things will turn out well, while acknowledging that it’s unlikely that they will.