There’s a branch of social psychology that concentrates on the study of various modes of conflict. One of those modes is called the ‘approach-avoidance’ conflict. It occurs when you’re simultaneously drawn to and repelled by a thing. For example, a person driving by a traffic accident might be drawn to look at the damage because of curiosity, but simultaneously repelled by what they see.

I find the photography of Roger Ballen to be a study in the approach-avoidance conflict. You want to look at it, and you don’t want to look at it. It’s not always easy to understand why you want to look at it, and it’s not always pleasant to examine the reasons you don’t want to look at it. Regardless, if you find yourself in the presence of a Ballen photograph, you will look it. And you’ll remember it.

Ballen, born in 1950 in New York City. He grew up in a photographically rich home. His mother, Adrienne Ballen, was one of the early members of the famous Magnum agency and the founder of Photography House, reportedly the first gallery in New York devoted strictly to photography. He was given his first camera at age 13.

His young adult life seems almost like a counterculture cliche. Ballen studied psychology at U.C. Berkeley, he attended (and photographed) the festival at Woodstock in the summer of 1969, then in 1973 he joined other peripatetic, well-to-do young folks and wandered through the ‘cool’ parts of the world trying to ‘find himself’ and photographing what he saw.

After spending time in Nepal, Greece, Indonesia and other hippie hotspots, Ballen seemed to take a counter-counterculture turn. He enrolled at the Colorado School of Mines in 1978; three years later he received his PhD in Mineral Economics.

He moved to South Africa (where his wife was from) and became a mining entrepreneur. That had two unexpected consequences. First, it brought Ballen to remote parts of South Africa where he encountered small villages called ‘dorps‘ populated by poor, marginalized white folks. Second, it sparked a desire to pick up a camera again and document what he was seeing.

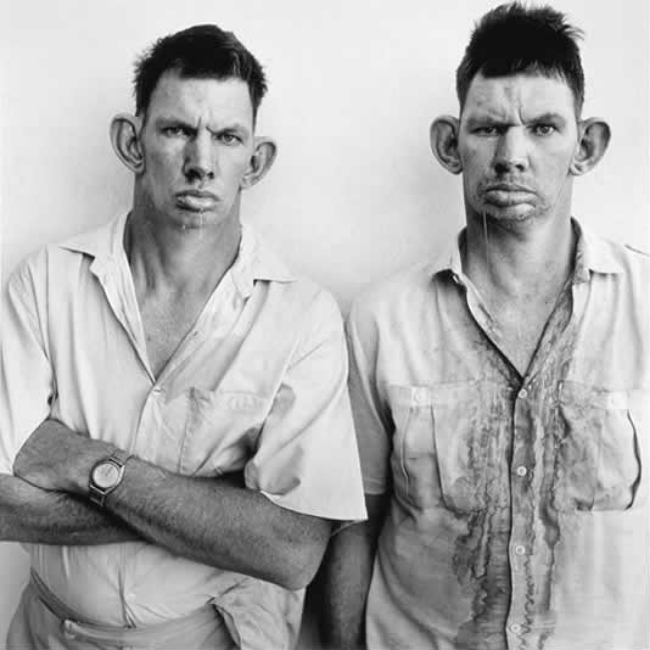

Ballen’s documentary photography was eventually published in 1994 under the title Platteland: Images of a Rural South Africa. The book sparked radically diverging critical responses. Some found it a work of unexpected power. No less a critic than Susan Sontag described the book as “the most important sequence of portraits I’ve seen in years.” Other critics felt Ballen was presenting a voyeuristic freak show and condemned Ballen for appealing to the viewer’s baser tastes.

Ballen, however, was still fairly isolated in rural South Africa and apparently paid little attention to the critics. His mining business was successful, which gave him the luxury of taking up the camera full time. He was no longer content, however, to simply document the world he encountered.

“I started to feel that the purpose of my photography was primarily to explore my own interior rather that the South African culture I was living in.”

Ballen’s interior, as presented in his photography, has a sort of Boo Radley ambience. There is an aura of desperate, demoralizing poverty to it along with a sense that something is profoundly broken. Inescapably broken. Perhaps incurably broken. Broken at a genetic level.

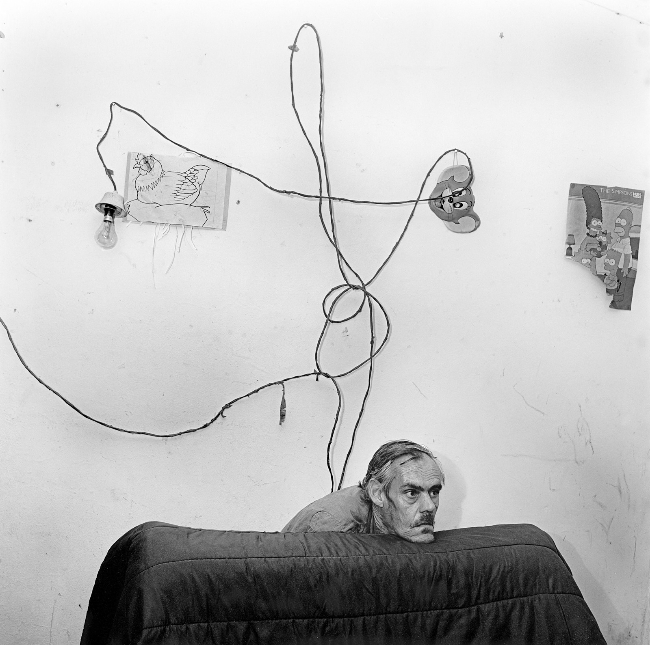

Once Ballen began to create imaginative images rather than document the world, his photography moved inside. His work takes place in windowless rooms, heightening the sense that his subjects are isolated, divorced from the larger society, cut off from any external influence. The settings are grim and grimy; the sort of deeply layered grime that can only accumulate after generations of unsanitary habits. The inescapable grottiness suggests that if cleanliness is next to godliness, then these poor souls are also isolated from god.

These settings aren’t just cheerless; it’s as if the inhabitants of Ballen’s photographs are completely unfamiliar with the entire concept of good cheer. That isn’t to insinuate that they’re singularly unhappy, but rather their circumstances have disposed them to anticipate and accept disappointment. They seem to have no notion of unalloyed or long-term happiness.

Ballen accentuates all that by incorporating certain visual elements of destitution into his photographs in unexpected and incongruous ways. Bare wires are strung around the settings in strange, discomforting and seemingly pointless patterns. Coat hangers are bent into weird shapes and hung in random places. Stained and moldy wallpaper is turned into eldritch cartoons. The overall effect is one of hopelessness without despair, an almost bovine acceptance of defeat.

That effect is further heightened by Ballen’s use of flash lighting. The direct, harsh light serves to flatten the perspective, both of the scene and of the subjects. He tends to place his subjects very near the back of the frame, literally against a wall. This makes it feel almost as if the subjects are pinned like moths to the glum walls of their existence.

It’s interesting to note that there is really no background in Ballen’s work. Everything within the frame is a meaningful part of the image. There is a sort of crammed minimalism at work here–a contradictory, busy sort of minimalism. Rather than having everything but the absolute essentials stripped away from the image, Ballen’s photographs feel like everything but the essentials have been starved away. There is no fat on these photographs; they’re all bone and gristle.

Although they look informal and haphazard, Ballen creates these photographs very deliberately. There is a conscious attempt to remove any sense of narrative from the image. A narrative, after all, exists to impose a developing sense of order over time. Ballen wants no narrative, no notion that something is developing. He wants to create a moment. Unlike Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment,’ in which the significance of an event is captured at the critical fraction of a second, Ballen’s moment never ends. He is indicating that the moment shown in the photograph is, in a very material sense, indistinguishable from the moment just before and the moment just after, or a moment a decade before or a decade after.

Ballen seems to be saying that this is what exists for these people. It’s all they’ve ever had and all they’ll ever have. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be: world without end. Amen.

Ballen’s post-Platteland photographs don’t depict any actual reality; the situations shown in his later work have no independent existence. They’re simply products of Ballen’s odd, idiosyncratic imagination. That they feel so real probably says something unsettling about humanity. We recognize them the way we recognize bad dreams–weirdly familiar and completely alien at the same time.

I can’t say I like Roger Ballen’s photography. But I am moved by it. And troubled by it. His work is compelling in uncomfortable ways. His photographs depict situations in which the human condition has been stropped to the sharpest of edges, and anything that sharp can cut you.

Ballen’s work cuts, cuts deep, and leaves an open wound.