She was born Gerta Pohorylle on 1 August, 1910 to a proper upper middle class Jewish family in Stuttgart, Germany. For most of her life, she lived a proper upper middle class life: a good education in Leipzig and at a Swiss boarding school, elegant balls, earnest discussions about art and politics with intelligent and well-read companions. But as she grew older, Germany became increasingly inhospitable to Jews.

As oppression of Jews and other groups became a matter of national policy, Gerta Pohorylle became more political. One night on her way to a dance she stopped to help some activists distribute anti-Nazi pamphlets. She was subsequently arrested and spent the night in jail, where she drew attention for being the only inmate dressed in evening wear. In 1933, after Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor, her family decided to leave Germany. Her parents left for Palestine, her brothers for England. Pohorylle decided to move to Paris.

In Paris she found work as a picture editor for Alliance Photo, an international picture agency. She met another displaced Jew, a young Hungarian man who was an aspiring photojournalist. His name was André Friedmann. Pohorylle and Friedmann became romantically involved and moved in together. Money was tight and the two devised a scam to increase their income. They decided to create a fictitious ‘famous’ American photographer and represent themselves as his agents. This imaginary photographer would, of course, demand higher rates than those being paid to young André Friedmann. They decided to call this photographer Robert Capa (Cápa was Friedmann’s nickname in Budapest; it means ‘shark).

Although their Robert Capa scam was quickly uncovered, the photographs were so good that they were forgiven. Friedmann decided to assume the name Robert Capa as his own. Gerta also began to shoot photographs under her own pseudonym: Gerda Taro (after Taro Okamoto, the Japanese artist). Where Capa took straight photojournalistic photographs, Taro followed the New Vision school. This school of art intended to shatter old traditions of perception and visual representation by using unfamiliar approaches: extreme angles, fragmented close-ups, strangely oriented horizon lines, abstract forms. The New Vision school was closely associated with the socialist movement; for Taro, photography was a political device as well as an insurgent art movement.

In 1936 civil war erupted in Spain. Fascist/Nationalist forces, backed by Nazi Germany, attempted a coup against the elected government of the Republic, comprised of socialist and liberal parties. As steadfast socialists, Capa and Taro left Paris and headed for Spain to cover the war.

Working with a medium format Rollieflex camera, Taro initially continued to shoot photographs in the same New Vision vein, making frankly propagandist images that celebrated socialist values. Her photograph of a woman volunteer could be an abstract fashion image. It’s all shape and form, it’s all about style and promoting the Republican/Loyalist cause. There’s not an ounce of realism or journalism in it. A bit of journalism filtered into her picture of the plucky boy at the barricades, but the centrality of the IFA (International Anarchist Federation) makes it primarily a propaganda photo.

Taro’s style changed radically when she accompanied Capa to the front lines. It changed for a couple of reasons. First, combat isn’t amenable to being posed; it’s a dynamic and unpredictably fluid process. In practice, combat photography might include many of the same elements of the New Vision school…the extreme angles, the fragmented close-ups, the strangely oriented horizon lines and abstract forms–but those elements are conditions of combat, not elements of design. Secondly, Taro discovered that the practices of war–the localized grunt work of bombing, killing and maiming–bear no resemblance to the idealized views of political philosophy.

The reality of that was made clear on 5 September, 1936. Taro and Capa accompanied some Loyalist volunteers on field maneuvers near Cordoba. The maneuvers were unexpectedly interrupted when they were ambushed by Nationalist troops. Taro had already used up all her film; Capa, however, shot the photograph that made him famous, the photo that has been called the greatest war photograph of all time. It shows a Loyalist soldier a split second after he has been shot.

When she returned from the front, Taro traded in her bulky Rolleiflex medium format camera for a small Leica. She abandoned the constraints of New Vision and began to shoot in a journalistic style. She and Capa believed the only way to document the realities of war was to be as close to it as possible. “That is really the only way in which to be able to understand the fighting,” Taro told a colleague. Capa’s comment on that approach is more widely quoted: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Taro lived that approach. She is believed to be the first woman photographer to accompany troops into combat.

As the civil war intensified, magazines and newspapers began asking for the work of Capa and Taro by name. Because they were often together, they sometimes published their work jointly under the byline of Capa/Taro. Each of them also traveled to the front lines on their own. Because she was petite and attractive, as well as almost recklessly brave, Taro received a lot of attention. To the Loyalist troops she was known as la pequeña rubia, the little blonde.

With or without Capa, Taro was everywhere in Spain, always seeking the action. She covered the failed Loyalist offensive of the Navacerrada Pass, which was later the subject of Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. She accompanied a team of dinamiteros, bomb-makers, on a mission in Madrid. She always sought out the locations where something was happening or about to happen.

There is little doubt that both Taro and Capa, like so many combat photographers and war correspondents after them, got caught up in the thrill of danger. After a year of war, however, Taro began to feel the weight of the same question asked by Hemingway’s characters, the question first articulated by 17th century poet John Donne: never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. She said as much to an interviewer:

“When you think of all the fine people we both know who have been killed even in one offensive, you get an absurd feeling that somehow it’s unfair still to be alive.”

In July of 1937 Taro and Federated Press reporter Ted Allan had gone to report on a battle near Brunete. On arrival, the commanding officer ordered them to leave immediately, saying they were expecting a major assault. Taro refused and Allan felt he couldn’t leave without her. They huddled in a shallow dugout while German Stuka dive-bombers dropped high explosives on the Loyalist lines. When they ran out of bombs, the pilots strafed the troops. Throughout the fighting Taro, according to Allan, continued to lean out of the dugout to shoot photographs. The assault began when the planes left. The Loyalist troops, courage shattered by the bombing and strafing, started to panic and broke ranks. Some of the soldiers attempted to stop the rout. Taro joined them, shouting at the fleeing men to reform their lines. It’s impossible to say if her voice helped quell the panic, but the troops did, in fact, reform and managed to repel the assault.

That evening Taro and Allan, having survived the assault, were returning on foot to the safety of a nearby village. Taro, who was scheduled to return to Paris the next day to meet with her publishers, saw the touring car belonging to the commanding officer who had earlier ordered them to leave the battlefield. The car was carrying wounded troops. Taro and Allan hitched a ride by hopping onto the car’s running board. Minutes later, as the car sped toward the field hospital, it was sideswiped by a tank. Taro was mangled in the accident and died the following morning.

Her body was returned to Paris. She was buried a few days later, on what would have been her 27th birthday. Capa, who had repeatedly asked Taro to marry him, was devastated and never fully recovered from her death. He continued as a combat photographer. His photographs of the D-Day landing are among the most famous war photographs ever made. After the end of World War II, he had a half dozen years of peace, then accepted an assignment to photograph the growing war between the French and Vietnamese. In May of 1954 he was killed by a landmine. Although he was occasionally involved with other women (including actress Ingrid Bergman–their relationship was fictionalized in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window), Capa never married.

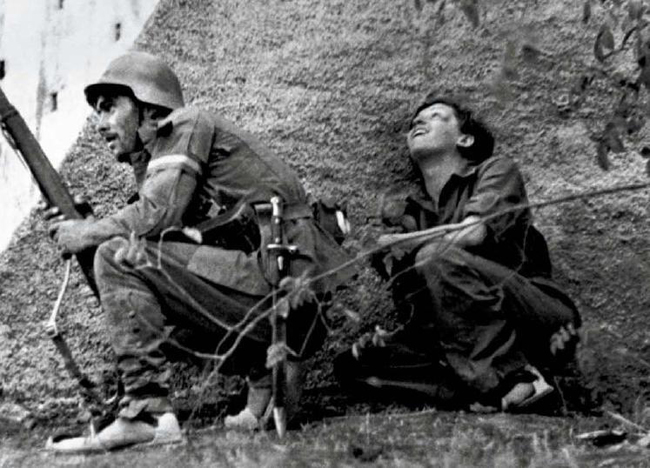

The photo above was taken by Capa. It shows Gerda Taro and a Loyalist soldier during a skirmish at the Cordoba front. Her career was short-lived but intense. Her work quickly disappeared from the public mind, overshadowed by the drama of the world war that followed the Spanish civil war, and by Capa’s own amazing work. Only recently has her photography–and the story of her life–begun to regain some small measure of its earlier promise.

Some lives, like Capa’s, are lived like a novel. Some lives are only short stories. Gerda Taro’s life was a haiku–brief but powerfully poignant.