For the first twenty-nine years of his life, he was pretty unremarkable. He was born in Detroit in 1912, took a degree in engineering from Michigan State, got a steady job in the Motor Parts division of Chrysler Corporation, met a good woman and got married. It was an ordinary life. Then, in 1938, he bought a camera.

To be accurate, the camera didn’t make any real difference in his life. At least not at first. Harry Callahan wanted a camera, but wasn’t sure what sort of camera. It was a toss-up between an inexpensive still camera–the pre-war version of a modern point and shoot camera–and more expensive 16mm movie camera. Callahan, only married for two years, opted to spend less money. He noodled around with the camera for three years, bought some darkroom equipment, and joined the camera club at Chrysler Motors. He was an unremarkable young man living an unremarkable life, taking unremarkable photographs. Then, in 1941, Ansel Adams gave a lecture and offered a workshop for the camera club.

Let’s be clear; it wasn’t the camera that changed things. Lots of people had cameras. It wasn’t the camera club that changed things; there were a lot of people in camera clubs. What changed things for Callahan was Adams himself. Callahan attended the lecture and took the workshop. By the end of the workshop, everything had changed. Everything.

The change was so profound that only five years later Callahan would be hired by Liszl Moholy-Nagy to teach photography at the Institute of Design in Chicago. Eventually he would help create the photography program at the Rhode Island School of Design.

What did Ansel Adams say that made such a difference? He said photography should be viewed on its own terms, as its own art form, not as a lesser form. He said photographing simple things was just as valid as photographing spectacular things. Callahan began to think about photography differently. In a very organic way, that led to him shooting differently.

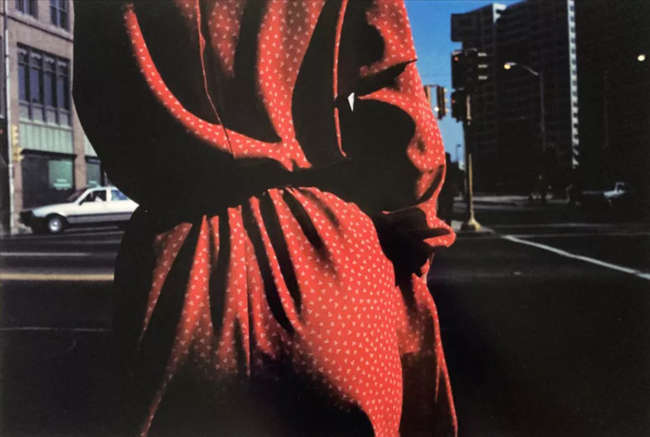

Although he tended to shoot intuitively, Callahan’s intuition was guided by a considered aesthetic. He thought about what he wanted. And what did he want? An intensified image. He wanted images that were powerful but simple. Sharp images with a strong element of design. Images that emphasized line, form, geometry. Callahan wanted to find those elements in the everyday world.

“The difference between the casual impression and the intensified image is about as great as that separating the average business letter from a poem.”

Callahan’s work has been described as tough and masculine. It’s been called cool–not in the modern sense of the term, but in the sense that there is a certain emotional distance in the work. It is, in a way, hard-boiled photography–photography that is unsentimental, firmly grounded in common life, realistic.

That lack of sentimentality even extended to his favorite human subjects: his wife Eleanor and his daughter Barbara. Callahan photographed these two–especially his wife–everywhere. On the streets of Chicago, on vacation in Italy, in the studio, in the countryside. He photographed them together and he photographed them separately, and he did it with the same matter-of-fact approach he used for all his work. When he was behind the camera, his wife and daughter were treated as subjects of photography, not as models and not as family.

The photographs weren’t about Eleanor and Barbara as individuals; they were, in effect, treated as design elements. They were often presented as small components in a large composition, but they always drew the eye. They might not dominate the image, but they were the essential point of balance that made the image work.

Through the late 1940s and 1950s Callahan developed a reputation as much for his work ethic as for his photography. He was out almost every day, regardless of weather, shooting photographs. Almost every evening he would develop the film he shot that day and make proof sheets. And yet he rarely showed the resulting images to anybody, not to his students and not to his fellow photographers. He would talk about the mechanics of photography and the technical aspects of cameras, he would talk about design and composition, he would talk about almost any aspect of the craft, but he rarely discussed his work.

That attitude is perfectly in keeping with his hard-boiled approach; if you do the work, there’s no need to talk about it. Unlike so many other photographers and artists, Callahan left almost no written accounts of his work or how he went about it. He kept no journal or diary, he didn’t maintain a scrapbook of his successes, he wrote no teaching notes, he saved no letters about sales or exhibitions. It was enough, apparently, to just go out and do the work.

Despite his work ethic, despite the fact that he shot photographs almost every day of the year and printed the proof sheets (after his death in 1999 it was discovered that he had more than 100,000 negatives and over 10,000 proof sheets), Callahan made relatively few final prints. He estimated he rarely produced more than dozen final images a year.

“Who said capturing reality is the point of photography anyway?”

Callahan asked that question during a 1983 interview. It may seem an odd thing to say, coming from a man whose work seems so solidly grounded in common life. The distinction, though, is between realism and reality.

Because of the emphasis on composition and design, Callahan’s photography is almost always balanced on the very edge of abstraction. He’s not attempting to present reality; he’s using facets of the real world to create strong elements of graphic design. Look again at his photographs. Instead of seeing the human figures as humans, see them as figures. It’s no accident that Callahan taught at institutes dedicated to design.

He had no formal photographic education, no formal education in design. But Harry Callahan had an engineer’s eye for structure and an intuitive grasp of composition. He became one of the most influential photographers of the middle-to-late 20th century, both through his teaching and through his exhibited work. It didn’t happen because he felt a need to express himself; it didn’t happen because he felt compelled to create art. It happened because he listened when Ansel Adams spoke. It happened because he changed the way he thought about photography. Then he went out and changed the way other people thought about photography.