Francesca Woodman was born in April of 1958 in Denver, Colorado. Both her parents were successful artists; her mother Betty was an accomplished ceramicist and art teacher, her father George, a painter and photographer. The family owned a summer near Florence, Italy and the Woodmans spent their summers there. Francesca attended both public schools and the Abbot Academy (the oldest private school for girls in New England, which merged with the Phillips Academy in Woodman’s second year). After graduation, she attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

She was, in almost every regard, a product of the U.S. upper middle class. Well-educated, well-read, well-traveled. Woodman had a privileged upbringing and that privilege was reflected in her approach to the arts. She began shooting photographs at the age of thirteen, using a Yashica twin lens reflex camera given to her by her father. It was a serious camera for somebody that age, a workhorse of a camera, a tool favored by artists.

Raised in an atmosphere in which the arts and academic sensibilities were combined, it seems almost a given that Francesca would become an artist herself. Her earliest images show a sophistication of approach. There were no frivolous snapshots of laughing friends at parties or school events, no photographs of sights seen on vacation with her family, no pictures of pets. Her earliest photographs are thoughtful and considered. They may be a tad naïve in style and composition, but they are very deliberately artful.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Woodman’s early work is that one can see the elements that would come to dominate her later work. It’s perhaps not surprising that her style evolved slowly until she arrived at RISD. At the university, her photography became both more methodical and more adventurous. She spent her last year of college (1977-78) in Rome as part of an honors program. Her fluent Italian and her family academic/art world connections allowed her to meet and become friends with Italian artists and academics. This was a period in which feminist avant-garde work was seizing the stage in academic art culture. That intellectual perspective shows in her work.

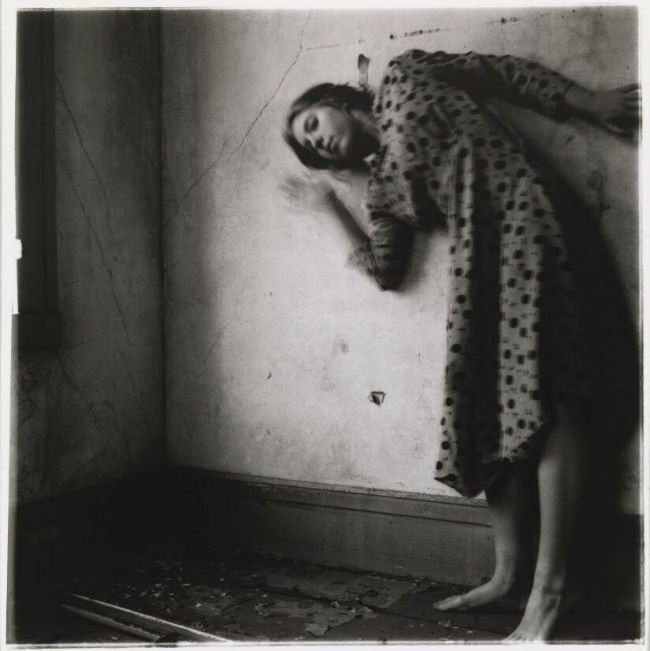

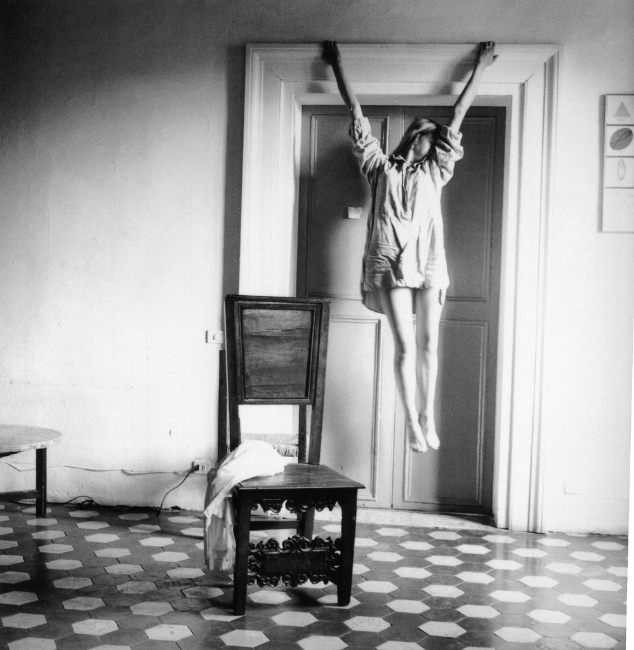

Most of Woodman’s photographs are self portraits–at least in the sense that she was her most frequent subject. Most of her photographs are interior pieces featuring nearly empty, nondescript, ramshackle rooms in what appear to be abandoned buildings. Most of her photographs are sober, sincere, and rather self-dramatic. It’s very earnest work.

Although she did produce a series of images that included a male friend, the vast majority of Woodman’s work revolves around the female body–usually her own. “It’s a matter of convenience,” she said. “I’m always available.” But even as an adolescent posing for herself, her photographs weren’t about her. She was simply the model in the photograph. That approach became more and more intentional as she matured as a woman and as a photographer. As her work progressed, Woodman as an individual–as a person–tends to disappear from the images. We rarely see her face; only her body.

In 1979, after graduating from RISD, Woodman moved to New York City to make a career in photography. She submitted her portfolio primarily to fashion photographers–a seemingly odd choice considering her work contains no hint of anything remotely fashionable. It is, in fact, almost aggressively anti-fashion. Perhaps that was the point; perhaps in some subconscious way she deliberately chose to derail any possibility of a career in commercial photography.

Although Woodman received no response from any of the fashion photographers to whom she’d sent her portfolio, she did manage to get some of her work exhibited in what are referred to as ‘alternative spaces.’ That was enough to earn her a slot as a summer artist-in-residence at the prestigious MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. When she returned to New York City Woodman put together a very short book entitled Some Disordered Interior Geometries.

It was a peculiar little book. Only 24 pages in length with sixteen photographs scattered among text and diagrams taken from an Italian geometry exercise book. It has been described as “a distinctively bizarre book…a seemingly deranged miasma of mathematical formulae, photographs of herself and scrawled, snaking, handwritten notes.” Very few copies were printed; it was distributed to her artist friends. Nobody had ever seen anything quite like it.

After completing the book–and, in fact, before many of the recipients of the book received their copies–Francesca Woodman jumped out the window of her New York loft and killed herself. She was a few months away from her twenty-third birthday.

Following her suicide, two things happened–one very predictable, one less so. Predictably, Woodman’s work began to receive attention, mostly from the academic art world. Her photographs were analyzed and examined through a variety of academic lenses. Here are a couple of examples:

“Her romantic, surreal, and often disturbing black and white photographs reference the history of modernist photography as well as presciently gesture towards more recent art about objectification and the female gaze.”

“Unlike most of the images we are faced with on a daily basis, where the body is treated like a commodity to be used and consumed, or an icon to adore at safe distance, Francesca Woodman employs her body to initiate a dialog with herself. She places her body in familiar settings, though at the limits of our experience, presenting it as a symbol of receptivity, a meeting place between herself and the rest of the world.”

Surprisingly, however, it apparently became almost taboo to consider her work in relation to her death. Although every article about Woodman refers to her suicide, the critics carefully avoid any suggestion that her work is anything but intellectual. There is rarely any suggestion that her photography might have actually been an indication of her emotional state.

Yet it’s difficult to look at Woodman’s work and not consider the gradual loss of the integrity of the self. The discontinuity between the softness of the body and the assertively gritty settings of most of her photographs isn’t accidental. The abandonment of the face isn’t accidental. The aura of tortured spirit isn’t accidental. The split between the deeply personal and the absence of intimacy isn’t accidental. Woodman’s photography might not have been an accurate barometer of her inner life, but there can be no doubt that in most of her work she understood what she was doing and she was doing it deliberately.

Woodman left behind an archive of more than ten thousand negatives, which are maintained by her parents. Fewer than 150 of her images have been published or exhibited in public. She has become something of a cult figure, influential to some students of photography in schools that place a heavy emphasis on theories of art.

There are sound reasons for that. Woodman’s work does address issues of body image and objectification, of women seizing control of the way they’re represented in art, of the exploration of the visible landscapes of the body and the invisible landscape of the mind. But I wonder if Francesca Woodman the person–the young woman who is both the subject and the object of the work–gets lost in all that.

The sad fact is, all we know of Francesca Woodman is the work she produced between the ages of 13 and 23. Who among us would want to be judged solely on what we produced in our formative years? Who knows what sort of work she’d have done had she not leapt out of that window? Perhaps she’d have moved outside the confined spaces present in most of her work. Perhaps her work would have become somewhat less grim and austere, less determinedly earnest. Perhaps she’d have reclaimed her own face.

That’s nothing but wishful thinking, of course. Francesca Woodman did jump out that window; her work is forever trapped by time.