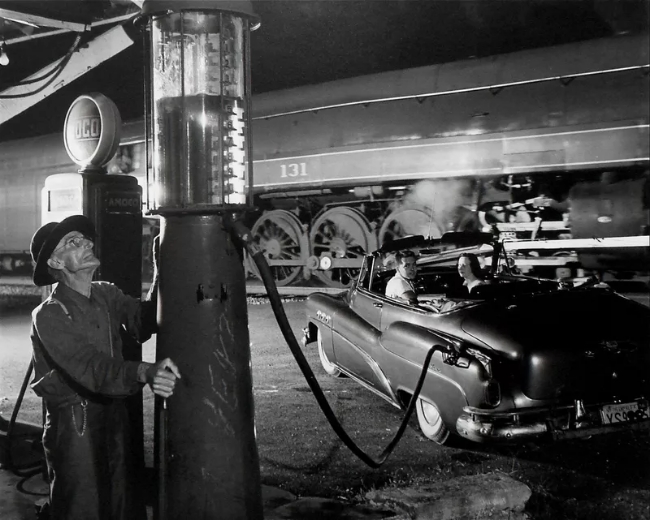

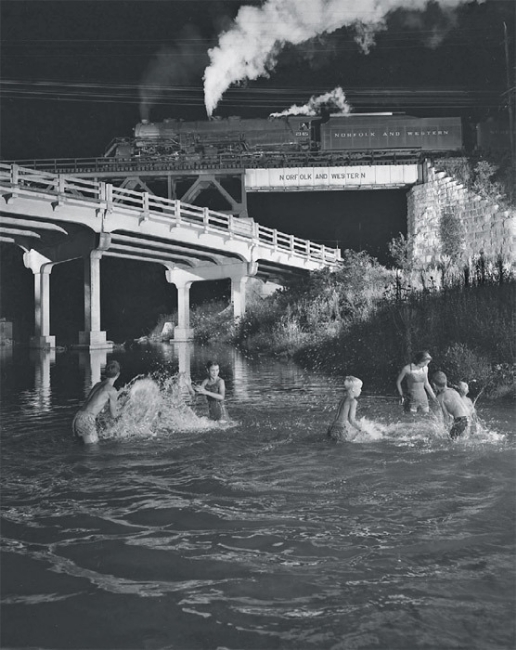

You’ve probably, at some point in your life seen one of the photographs on this page. They’ve become an facet of Americana, wistful representations of a bygone era in which steam locomotives transported goods and people across the huge expanse of the North American continent. The train photographs of O. Winston Link have taken their place beside the paintings of Norman Rockwell as cultural artifacts of a simpler time and place.

They are, in fact, much more than that.

He was born in 1914, the year the Great War began, and was given the unfortunate name of Ogle Winston Link. He grew up in Brookyn; attended the Manual Arts High School and later the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, where he earned a degree in civil engineering. Although the term hadn’t been coined yet, Winston Link was an engineering geek. He’d always been interested mechanical things; that included cameras as well as trains. He began taking photographs in high school with a borrowed Kodak medium format camera. He built his own enlarger for the darkroom (which he also built himself). He and his friends periodically took the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan, then the ferry across the Hudson to New Jersey, where they would spend the day wandering with their cameras through the railyards of the Jersey Central or B&O railways.

Link received his civil engineering degree in 1937, during the final years of the Great Depression, a time when engineering jobs were scarce. However, based on his experience as photo editor of the university newspaper and his skill at public speaking, he was offered a job as a staff photographer for a large public relations firm. His job was to shoot photographs for the firm’s clients–photos that would be offered to local newspapers for free. The photos therefore had to be interesting enough that the newspaper would find a reason to print them.

Link learned how to make carefully posed photographs look candid. He learned valuable ‘social engineering’ skills that allowed him to convince the heads of corporations–a notoriously conservative group–to let him try new things. He learned how to use flash lighting to illuminate those things he wanted to illuminate and to disguise or hide the things he didn’t want seen. Those skills would serve him well over the course of his career.

The Second World War interrupted his public relations career. Link was found to be unfit for military service, the result of partial hearing loss from a childhood bout with epidemic parotitis (the mumps). Instead he went to work for the Airborne Instrument Laboratory, where he photographed the work being done to create a device that would allow low-flying aircraft to detect submarine activity.

Coincidentally, the lab was located next to the tracks operated by the Long Island Railroad. Link’s interest in trains was renewed.

At the of the war, Link opened his own commercial photography studio–first in Brooklyn, later in Manhattan. He quickly developed a reputation for being the best at photographing complicated factory and industrial interiors. This was primarily because of his skill at lighting. Link built his own lighting systems, complex affairs involving dozens of linked flash units.

In 1955 Link accepted an assignment from Westinghouse to photograph a factory in Staunton, Virginia where window air-conditioners were assembled. The assignment brought him near the Norfolk & Western Railroad, one of the last railroads in the U.S. using steam locomotives (most other railroads had converted to diesel-powered engines).

Link was seized with the idea of photographing the last of the steam locomotives. He contacted the owner of the railroad and convinced him to grant permission for Link to have access to the railroad’s tracks, railyards, shops and workers. He worked on the project for the next five years, photographing the trains and the railroad workers and the communities through which the trains traveled. He did it all at his own expense, traveling from New York to Virginia and West Virginia more than twenty times.

The steam locomotive was a marvel of industrial-age technology. It was an incredibly complex and labor-intensive mode of transportation. It is, in effect, a giant boiler attached to wheels, a massive steel tube in which water is superheated to the point where it is ready to explode. The energy created by the steam is channeled through a series of valves and cylinders to sets of pistons which then turn the wheels; enough energy to move several thousand tons of engine and cargo-laden railroad cars at high speed. This was the technology by which the continent of North America was ‘conquered.’

It was also outdated. Even in the mid-1950s, Link saw the steam locomotive through a lens of romanticism. The photographs he made are deeply romantic photos; idealized, sentimental, and folksy even while celebrating a form of technology.

But as I noted earlier, they are very much more than that. Winston Link’s train photographs are also amazing for their innovative technique. Night photography wasn’t entirely uncommon in the 1950s, but self-illuminated night photography was rather rare. Once again, Link had to build his own illumination systems, serially linking more than 60 different flash units–and it should be noted these units used flash bulbs–with up to three large format cameras.

Consider the degree of difficulty involved. Link would have a general idea when the train would pass by a certain location (trains, after all, keep to a tight schedule), but he only had one chance to catch the train in the right spot. When a flash bulb is lighted, the bulb is rendered useless; each flash bulb must be replaced by hand before the flash unit can work again. On top of that, because he had to link the flash units serially, if one bulb failed to illuminate, all the subsequent bulbs would fail. The lighting units had to be carefully placed to illuminate only the parts of the composition Link wanted to illuminate. Because of the time involved in setting up the shots, test shots weren’t practical. And to make matters still more complicated, all the people in the photo had to be positioned and posed in advance, waiting on the arrival of the train. And, of course, much of this work had to be done in the dark. The result of all that effort would be one shot, a mere 60th of a second which couldn’t be repeated until another steam locomotive passed the same spot at a later time.

Link took his last photograph of the steam locomotives in 1960. In the five years he worked on the project, he made more than 2400 exposures (most of which were shot in daylight hours). Except for a few publications in railroad magazines, the photographs were universally ignored. Link had also made sound recordings of the steam engines, and those recordings found an audience among rail fanciers. In the late 1950s he issued a set of six gramophone records of steam engines.

It wasn’t until twenty-three years after he shot his last steam engine photograph that people began to pay attention to the photographs. In 1983, the year he retired from business, Link’s train photos were included in a traveling exhibition. They became a massive hit and his prints and posters began to sell widely.

Sadly, Winston Link’s late success brought unexpected consequences. In 1984, at the age of 70, Link married his second wife, Conchita Mendoza, twenty years his junior. It is alleged that after a few years of marriage, Mendoza kept Link a virtual prisoner, locked in the cellar where his darkroom was located. She required him to make and sign prints, which she then sold. She notified all the art dealers and galleries that Link was suffering from Alzheimer’s and that all exhibits, correspondence and financial dealing should be done through her.

A gallery owner luckily discovered what was going on and sparked an investigation in which it was determined that Mendoza had stolen more than a quarter of a million dollars from Link’s bank accounts (more than $60 thousand of which was given to a lover), as well as stealing his prints and negatives. Although she denied the thefts, she was convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to six and half years in prison.

Winston Link, after receiving a welcome divorce from Mendoza, returned to public life. Although his negatives were missing, he participated in the planning of an O. Winston Link museum to be located in the historic Norfolk & Western Passenger station in Roanoke, Virginia. In January of 2001 Link suffered a heart attack. He apparently decided to drive himself to the hospital. On the way, however, his condition worsened; he pulled his car off the road and died. Coincidentally, he was parked outside the train station.

Link’s ex-wife, Conchita Mendoza, was released from prison in November of 2002. In early 2003 she was discovered selling signed prints by Winston Link on E-Bay. She was again arrested and in the subsequent investigation, a storage facility in her name was discovered in Gettysburg, PA. It contained thousands of Link’s prints, as well as his missing negatives and transparencies.