There is a long history of social documentary photography in the United States. Before there was Milt Rogovin, before John Vachon, even before Lewis Hine, there was Jacob Riis.

Riis was born in Ribe, Denmark in 1849, the third of fifteen children. Although his father had been a teacher and the editor of the Ribe newspaper, young Jacob became a carpenter. At age 16, two critical events happened in his life. First, he fell in love with Elisabeth Gjørtz, the daughter of a relatively wealthy Ribe family. Elisabeth’s parents did not approve of Riis, and when he asked her to marry him, she declined. That prompted the second critical event. Riis decided to move to Copenhagen, find work, earn a fortune, and make himself worthy of Elisabeth Gjørtz. Five years later, in 1870, Riis, having failed to make his fortune or become worthy of Miss Gjørtz, took a steamer to New York City. He had the equivalent of US$40 and a gold locket with a strand of Miss Gjørtz’s hair.

He was one of some twenty-five million immigrants who immigrated to the U.S. in the years surrounding the American Civil War. Most of those immigrants settled (at least temporarily) in one of the major East Coast cities: Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore. They turned the poorest parts of those cities into ethnic enclaves. The cities, not surprisingly, were overwhelmed and many of those immigrants found themselves living in dire poverty.

Like so many other immigrants, Riis arrived in New York City with almost no money. He spent the next three years living hand-to-mouth, working occasional odd jobs, sleeping in the lodging houses operated the police department. Despite the fact that they were associated with the NYPD, these lodging houses were infamous for the level of crime and violence. They were still, however, safer than sleeping on the streets.

Riis occasionally considered suicide. At one of his lowest points he encountered a small stray dog. The dog reminded him of his childhood pet, Othello. Riis adopted the dog, which gave him a reason to live. Some time later, while sleeping in a police lodging house, Riis awoke to discover somebody had stolen the small gold locket he wore around his neck–the locket containing the strand of Miss Gjørtz’s hair, and the last relic of his life in Denmark. When he complained to the police officer in charge, the officer summarily tossed him out of the lodging house and beat him. When Riis’ dog barked and bared his teeth, the officer used his nightstick to club the dog to death. A short time later, he learned Miss Gjørtz had become engaged to a cavalry officer.

Riis spent the next year doing odd jobs to stay alive. In 1874, he learned the New York News Association was looking for a trainee. He applied for the position, was hired, and before long became a reporter with one of the many New York City newspapers, the New York Evening Sun. He was given the newspaper’s least prestigious and least rewarding job: police reporter. Because he was familiar with the streets, Riis was a natural for the job. He was willing to go to the crime-ridden parts of town other police reporters were reluctant to visit.

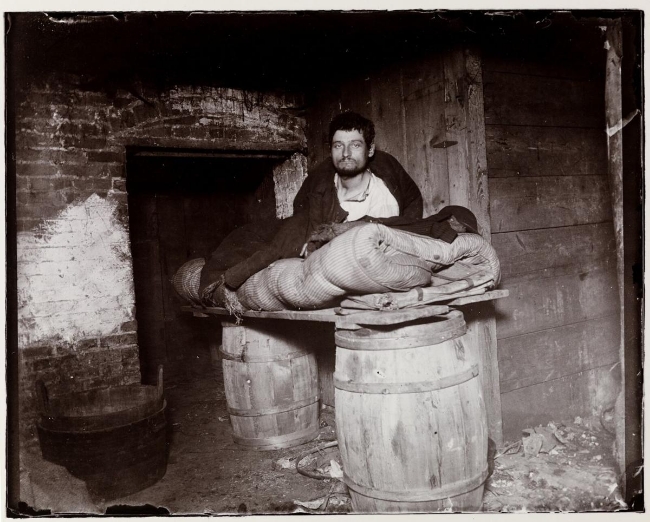

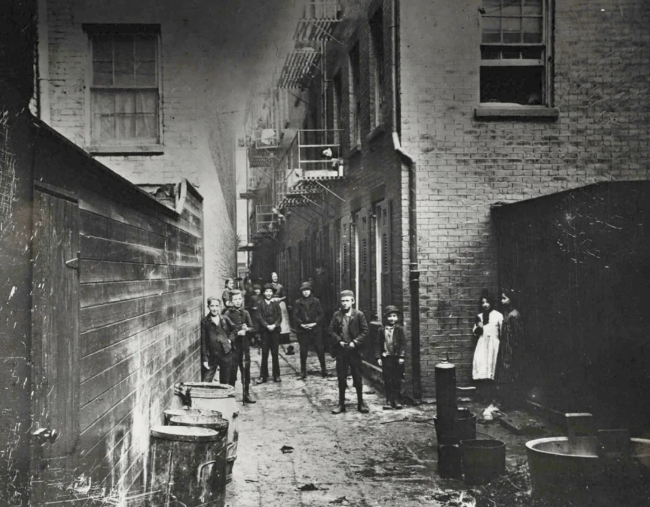

The heart–or, more appropriately, the dark soul–of New York City’s crime-ridden slum life in the mid-to-late 1870s was located between Mulberry Bend and the Five Points area. The levels of population density, disease, infant and child mortality, unemployment, prostitution, violent crime, drug abuse and general destitution in this area were staggering. Brothels, opium dens, gambling houses, dog-fighting venues were common. In the 1890s, after the area had been ‘cleaned up’ enough to allow a census, it was discovered that only 24 of the more than 600 tenement houses was considered safe for habitation.

This became Riis’ beat. He wanted his readers to understand what life was like in this area; he wanted them to become outraged enough to act and change the living conditions. His reporting drew attention–though not as much as he wanted–and before long Riis became the success he’d always wanted to be. He moved from newspaper to newspaper, each of which gave him a raise.

Although his reporting on the living conditions gained notoriety and attention, Riis felt he wasn’t having a significant impact. He considered taking photographs so the readers could see what he saw, but the streets were narrow and there was rarely enough direct light to photograph the activity he wanted to show. Besides, the most interesting aspects of slum life took place after dark. In the 1880s, night photography was virtually non-existent. Then, in 1887, Riis came across a brief mention of the invention of magnesium flash powder in Germany. Riis decided to try it. The result was completely unexpected.

The use of flash powder for artificial lighting in photography was not only still experimental, it was actually dangerous. The magnesium-based flash powder used by Riis is essentially the same technology on which modern stun grenades are based. Because no device had yet been invented for using flash powder as a photographic aid, Riis relied on a cast-iron frying pan. He would set up his camera (a cumbersome large format unit on a wooden tripod), open the shutter, close his eyes, and ignite the flash. Once he set his own clothing ablaze; twice he set the establishments he was photographing on fire. But the photographs that resulted from this process changed New York City.

It was one thing for newspaper subscribers to read Riis’ accounts of life in the slums, illustrated by ink sketches. It was quite another for them to see actual photographs of slum life. Riis wrote an account for Scribner’s Magazine, which was published in the December 1889 issue–just in time for Christmas. The response to that article led Riis to write a book about the relationship between poverty, crime, deviance, and public health. The book was entitled How the Other Half Lives.

The Scribner’s article and the subsequent book caught the attention of the New York Police Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt (who, twelve years later, would become President of the United States). Roosevelt began to accompany Riis on his nighttime sojourns into the slums, where he discovered the level of corruption and violence in the police lodging houses (as well as police officers sleeping instead of making their rounds, not to mention committing crimes of their own). Roosevelt instituted a reform movement, closing down the lodging houses and replacing them with a municipal boarding house system overseen by local charities. Largely as a result of his work, many of the tenements of Mulberry Bend and Five Points were razed, replaced in part by parks and civic buildings.

Roosevelt called Riis “the most useful citizen of New York,” and coined the term “muckraking” to describe his brand of public interest journalism. With his fame in the city growing and his new connection with the most senior police official in the department, Riis considered locating the police officer who had clubbed his dog to death and ruining that man’s career. He later described his decision not to track that officer down as “the biggest fight” of his life.

Riis continued muckraking for the next twenty-five years. He not only continued to write for newspapers, he also wrote several books and maintained an active schedule of speeches which he illustrated with ‘magic lantern’ slides of his photographs. The audience response to the photographs was dramatic, according to one contemporary account. They moaned, shuddered, and even fainted at images showing children sleeping on the hard floors of dark stairwells, young women aged and bent from years of rag-picking, gangs of orphaned or abandoned children roaming the streets and stealing from fruit carts.

Many modern critics, while appreciating the documentary nature of Riis’ work and his reformist zeal, have criticized him for broad racial and ethnic stereotyping. He generally describes the influx of free blacks and emancipated slaves into New York as being cheerful but lazy, but still “immensely the superior of the lowest of the whites, the Italians and the Polish Jews.” Riis was particularly prejudiced against Chinese immigrants, writing:

…all attempts to make an effective Christian of John Chinaman will remain abortive in this generation; of the next I have, if anything, less hope. Ages of senseless idolatry, a mere grub-worship, have left him without the essential qualities for appreciating the gentle teachings of a faith whose motive and unselfish spirit are alike beyond his grasp.

While these attitudes are certainly reprehensible, I’m inclined to be somewhat tolerant of them in Riis’ case. He was, after all, a product of his time and culture. Despite his deep prejudices, he worked tirelessly until his death in 1914 to improve the living conditions of all the poor–even those he felt were somehow inferior.

Jacob Riis was one of the first photojournalists, he was among the first experimenters with flash photography, he was the original muckraker, he inspired social awareness in political circles, and he made the public aware of the plight of children in poverty.

This has nothing to do with his photography, but as Riis’ success grew and he became more financially stable, he received a letter from his family in Denmark telling him Elisabeth Gjørtz’s fiancé–the dashing cavalry officer–had died. Riis wrote to her, renewing his proposal. This time she accepted. In the end, I don’t think there’s any doubt that he proved himself to his childhood sweetheart.