She was born in 1935–perhaps in Romania, perhaps in Paris; there is some uncertainty. Her parents are said to have been in the circus–perhaps as performers, perhaps in some other capacity; there is some uncertainty. She spent her childhood years in Constanta, Romania or perhaps traveling; again, there is some uncertainty. She was apparently a painter before she took up the camera, though I’ve found no examples of her painting. There is, as always, some uncertainty.

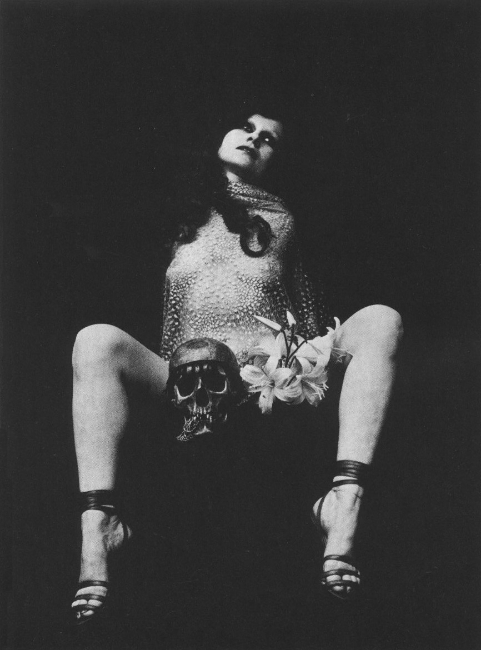

What is known for certain is that in the early 1970s Irina Ionesco appeared unexpectedly in the Parisian art photography community with a collection of strange and erotic black and white photographs. The photographs (some of which were self-portraits) were primarily portraits of women partially-dressed in elaborate costumes, surrounded by unusual or bizarre props. While some of the portraits are fairly straightforward, many include elements that are distinctly fetishistic. In those early photographs, the women are often looking toward the camera in a disinterested way–as if they are unimpressed and unconcerned by the viewer’s attention.

By 1974, only a few years after her arrival on the art scene, her work was on display in the Nikon Gallery in Paris. Her photographs were being featured in a variety of art and fashion magazines, and sold in galleries throughout Europe and Asia. She was hired by Vogue and other magazines to shoot fashion spreads. She went from obscurity to fame (a rather localized sort of fame, to be sure, but fame nonetheless) in an astonishingly short time.

Ionesco had given birth to a daughter, Eva, in 1965. Not surprisingly, she often photographed little Eva. At some point in the early 1970s Ionesco began to photograph her daughter in much the same way she photographed adult women: dressed in lavish costumes, amid props that seem to have some strange symbolic meaning, partially dressed, in erotic poses.

Even in Paris, even in Paris of the mid-1970s, the photographs of young Eva Ionesco sparked controversy. Some critics hailed them as works of unparalleled genius, a commentary on the balance point between organic virginal beauty and manufactured eroticism. Not surprisingly, many people decried them as blatant child pornography. Just about everybody found the photographs profoundly disturbing in one way or another.

Ionesco, it seems, simply gave a Gallic shrug to the fuss and went on about her business, apparently ignoring both the critics who praised her and the critics who upbraided her. She continued to shoot photographs for fashion magazines, for the art galleries, and for herself. She continued to photograph her daughter as well as adult women. She did a photo shoot for Vogue Japan using Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as the theme. Her use of children as models could be interpreted as blithe ignorance of the scope of the controversy over Eva’s portraits or as a deliberate statement that she would shoot the photographs she wanted to shoot, regardless of complaints about her.

“Decadent poetry, symbolist paintings, Hollywood films, Greek tragedies, kitsch sublimated or the sublime consecrated. I like artificial paradises, the magic of false luxury, that which one invents, which one creates through the play of multiple imaginary looking glasses.”

Ionesco began to lose some of her supporters when she allowed her daughter to pose for Playboy in 1975, and then for the Spanish edition of Penthouse in 1976, when Eva was still only 11 years old. Ionesco also allowed Eva to act in a Roman Polanski film, Le Locataire. This was two years before Polanski would plead guilty in the U.S. to a charge of unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor (it should be noted that there is no suggestion that anything untoward happened between Polanski and Eva). However, the Polanski case ignited more controversy for Ionesco. For her part, she continued to allow Eva to act in other films, most of which were respectable. Yet she also permitted her to appear in a sci-fi soft-core porn movie called Spermula. With each questionable decision she made in regard to her daughter’s career, Ionesco lost some of her support.

After that first flush of success, Ionesco’s work became fairly static. That isn’t to suggest she disappeared from the art scene. She continues to sell her photographs in galleries and seems to have no trouble finding fashion work. In 1996, when she was in her early 60s, Ionesco was exhibiting her work (primarily her older work) at galleries in Tokyo and her name was still powerful enough to get her an invitation to shoot portraits of local Yakuza leaders–a rare event.

Ionesco is seemingly completely unfazed by the fact that she was briefly notorious in European art circles. By all accounts she retains a close relationship with her daughter. Eva used the money she earned as a child and teenager to attend the Theater des Amandiers, one of the most exclusive schools for the performing arts in France, and she continues to work in films in Europe.

Although the furor over Ionesco’s photographs of her daughter has abated, the controversy still remains. Are the photographs art, or is it pornography? Does the fact that the photos were made by her mother make the photographs more offensive or less offensive? Are the photographs more controversial because they show Eva in age-inappropriate clothing? At what point does it become appropriate for innocence to wear the trappings of adult sensuality? By dressing her in nylons, does the photograph become erotic or absurd? Or both?

I confess, I was–and still am–hesitant to include Irina Ionesco in the Sunday Salon series. I originally did the research for this two months ago, and I’ve spent the intervening period of time debating whether or not to follow through on it. Obviously, I came to the conclusion to publish it, though I’ve chosen not to include some of the more explicit photographs.

Some people claim it is the job of artists to examine social taboos. I disagree; I’m inclined to think it is the job of artists to make art–and sometimes making art includes an examination of what society finds offensive and/or forbidden. I am less troubled by Ionesco’s portraits of her daughter than I am by her decision to allow her daughter to be photographed by magazines like Penthouse and appear in soft core porn movies. To me, the former is an artistic decision; the latter is an economic decision. At the same time, I have to admit that that economic decision allowed Eva Ionesco to attend a very exclusive and expensive school. At this distance, it is impossible to determine if the experience harmed Eva in any way. Eva has maintained it hasn’t. All we can do is take her at her word.

In the end, it seems to me the questions raised by the work of Irina Ionesco are worthy of discussion. Perhaps that is the primary value of her work.