NUDE IMAGE NUDE IMAGE NUDE IMAGE

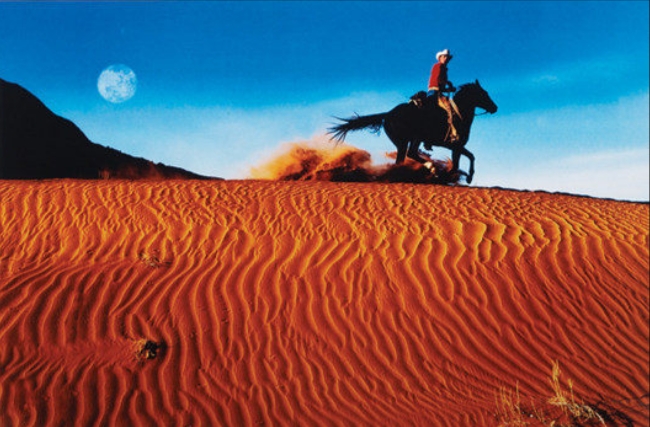

Richard Prince was the first photographer whose work sold for more than a million dollars. It happened in 2005 in New York City at Christie’s auction house. The photograph (pictured below) was one of a very limited series of images, all of which shared the same title: Untitled (Cowboy).

This photograph may remind you of the Marlboro Man, a classic cigarette advertising campaign from the 1970s. There’s a good reason for that. The photograph Prince sold for a million dollars in 2005 is, in fact, the Marlboro Man. Not just a similar model riding a similar horse in a similar outfit in a similar setting. It’s the very same photograph shot by commercial photographer Sam Abell.

About thirty years after Abell shot the original photo, Prince photographed Abell’s photo without the text, put his name on it, and sold it for a world record price. Three years later, in 2008, he broke the world record again–with another photo from Abell’s Cowboy series; this time for US$3.4 million.

None of that money went to Sam Abell.

You may be wondering, “Who the hell is Richard Prince? And how is he able to get by with this?” Good questions.

Prince was born in 1949 in the U.S. controlled Panama Canal Zone but grew up in Braintree, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. He knew at an early age that he wanted to be an artist. Although he apparently studied painting in college, he doesn’t seem to have been very committed to the medium. After graduating from college, Prince moved to New York City and took a job with Time-Life magazine–not as an artist, but in the tear-sheets department.

A tear-sheet is a page cut from a magazine and used as proof of publication. Prince’s job was to cut out the articles and/or images in each publication to be sent to the writers and photographers published in that issue. “At the end of the day,” Prince told an interviewer, “all I was left with was the advertising images.”

He became fascinated with the unreality of advertising and began to incorporate cut-out ad images into collage-paintings. It wasn’t a new technique; Picasso had used it as early as 1912. By 1977 Prince had stopped bothering with paint and glue and began to “appropriate” images by the simple process of re-photographing them. His first major project was the Untitled (Cowboy) series, which came to define his career.

How is this art? If Prince is merely re-photographing another person’s image, how can he be considered an artist? According to Prince and his supporters, the appropriation of another person’s work can ‘additionalize’ the reality of the original image. It can create “a reality that has the chance of looking real, but a reality that doesn’t have any chance of being real.”

Prince would suggest his Cowboy series isn’t about cowboys; it’s about popular culture. It’s a commentary on the way images are used to create a false appearance of reality. The original Marlboro Man photographs, after all, weren’t documentary; they didn’t show real cowboys doing real cowhand work. Those photographs were deliberately designed to draw a specific buyer market and increase the sales of Marlboro cigarettes. The original advertisements are models of irony; they appear to promote a healthy outdoor life while actually selling a carcinogenic product. They are romantic images showing hyper-masculine models in romantic poses while roaming a romantic hyper-American landscape that doesn’t really exist in the way its presented. Sam Abell’s photographs are, in a very real way, fakes. Prince asserts that by appropriating those fakes–by making fake fakes, in other words–he is drawing attention to the fraudulent nature of the imagery that constructs popular culture.

Prince claims that by intervening in the process begun by Sam Abell, the original Marlboro Man photographer, he is creating new art. By removing the image from its original context, Prince says he is adding new layers of meaning to the work. What was originally merely a commercial endeavor becomes transformed into art.

When asked why he should make millions off photographs taken by somebody else, Prince is justified in asking how much money Phillip Morris (the manufacturer of Marlboro cigarettes) made from the photographs. Art, he insists (correctly, in my opinion) is valued differently from commercial images. An image created to sell a product is valued differently than an image created to exist as art.

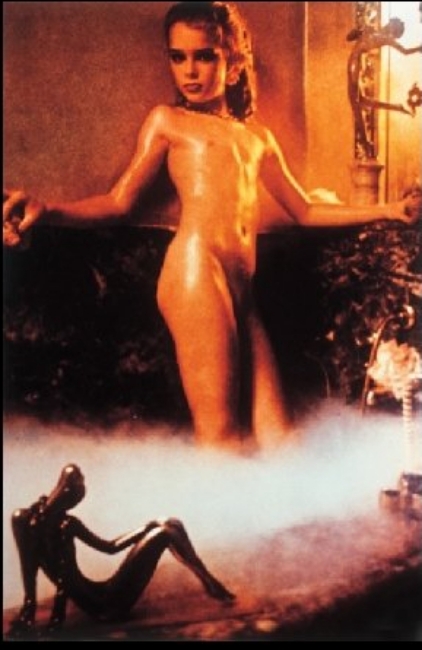

The outrage and indignation sparked by Prince’s Cowboy series may have started the debate, but it reached its peak in 1983 with a project called Spiritual America and the nude photograph of child actor Brooke Shields.

In 1975 Terrie Shields, in exchange for $450, gave the unfortunately-named photographer Garry Gross permission to photograph her ten year old daughter in the nude. Gross had young Brooke’s face made up like an adult and her body oiled, then posed her in a faux Grecian setting. The resulting photographs were disturbing and created something of a scandal–although they apparently served the purpose of Terrie Shields. A year later Brooke was cast in a Louis Malle film, Pretty Baby, in which she played a child raised in a brothel. The film contained several nude scenes.

In 1981, Terrie Shields sued Gross to gain control over the photographs. The case would take three years to resolve in favor of Gross. In 1983, while the case was still being tried, Prince re-photographed one of the images taken by Gross.

Prince entitled the photo By Richard Prince, A Photograph of Brooke Shields by Garry Gross, but the photo is better known by the title given to the entire project: Spiritual America. The project involved renting a storefront in New York and turning into a gallery (also called Spiritual America) which only showed a single photograph–the one of Brooke Shields. The gallery was not free and wasn’t open to the public. The gallery, according to Prince, “was in fact a sideshow, another frame around the picture, another attraction around the portrait of Brooke Shields.”

The entire elaborate production surrounding Spiritual America was, for Prince, part of the art. The work wasn’t about the original photograph, the photograph was merely the object that initiated the art. Not only was the original photo itself an object, it had turned the ten year old Brooke Shields into an object–an object with a sensuous woman’s face attached to a sexless child’s body. “Brooke as the subject becomes an indirect object, an abstract entity,” Prince said. When he took the picture of the picture he was photographing one object depicting another object, all of which had been sparked by a mother treating her living child as an object. Prince then displayed his recreated object in a way that emphasized its objectness. He not only appropriated the photograph at the center of the project, he even appropriated the title of the project: the original Spiritual America is a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz showing a gelded horse.

Prince’s photo eventually sold for a mere $150,000 and was put on display in the Whitney Museum of Art in New York City. Gross, on the other hand, tried to sell prints of his original photographs on eBay for $75 to $200. However, eBay found the images objectionable and removed them from their site. Why is Prince’s copy considered valuable art whereas Gross’s original photo considered objectionable? Motive and intent, on the part of the photographer and on the part of the viewer.

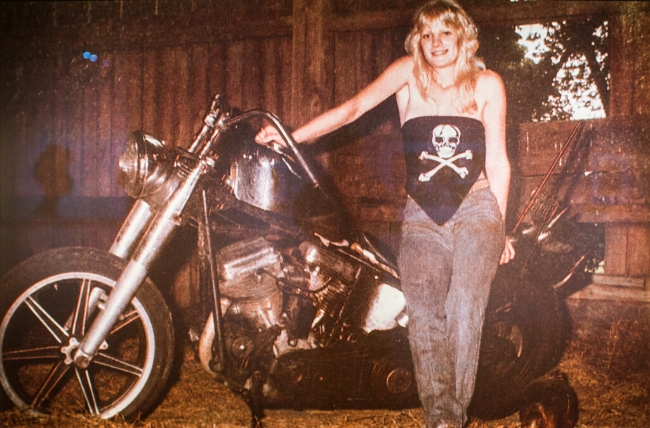

Prince continued to use the same appropriation technique to examine aspects of American popular culture and its influence. One such project involved re-photographing pictures published in the back pages of motorcycle magazines such as EasyRiders. The photographs were taken by amateurs to show off both their motorcycles and their girlfriends.

Prince saw those images as being at least in part about property; the biker-photographers were showing off their prized possessions–one of which happened to be a woman. He was also struck by the fact that the women in the photographs were seemingly complicit in objectifying themselves. The poses struck by the women were awkward and uneasy copies of the poses often seen in magazines like Playboy…poses that are themselves artificial. Again, Prince is playing with that free-floating notion of what is real, what is copied, and how one is able to tell the difference.

And, again, there is that uniquely American aspect to the project. The American biker is the modern version of the myth of the American Cowboy, who is really just another version of the American Frontiersman (like Davy Crockett and Natty Bumppo). The lone man, free from civilization, making his own rules, apart from society but still iconic of that society. By removing the photographs of motorcycles and biker babes from their original context, Prince encourages people to actually look at them–at the people who are attempting to become part of the various myths offered them by popular culture. He hopes to rouse people to ask how those myths–cowboy, sexy model, biker–took root in modern culture and why they remain so powerful.

Prince now works in other media as well as photography, but he retains the same subversive sensibility. In the end, I think, his work is never about the actual thing on display; it’s always about how society–and particularly American society–obsessively consumes myth and fakery, and continuously regurgitates it.

Does that mean his work is art? Does that make him an artist? I don’t know. Now I can’t help asking if our definitions of art and who is an artist are also based on nothing more than myth and ideas that repeated again and again in popular culture.