One of the problems inherent in looking at the work of a photographer–or any artist or artisan or craftsperson–is trying to decide what information is important and what isn’t.

How much does it matter that Elliot Erwitt was born Elio Romano Erwitz in Paris eighty years ago this week? Does it matter that he was the only child of Russian émigrés who’d fled the 1917 Revolution a decade earlier? Or that shortly after his birth, the family moved to Milan, or that his parents separated when he was four years old under what he described as “rather acrimonious circumstances“? Is it important to know that the rise of fascism in Italy during the 1930s forced his family to temporarily re-unite and flee back to France?

Surely it matters that they immigrated to the United States, literally catching the last ship out of France before the French government officially declared war against Nazi Germany. On his arrival in New York City in 1939 his name was noted as Elliot Erwitt. He was eleven years old and spoke no English, though he was fluent in Russian, French and Italian. His parents separated again, with Erwitt living primarily with his father. Two years later, his father abruptly decided to move to California, taking young Elliot with him. They traveled across country by car, selling cheap wristwatches along the way to support themselves. They settled in Hollywood.

Maybe all that information matters. It probably does. But this certainly does: Erwitt earned extra money after school by working in a commercial darkroom, processing and printing photographs of movie stars. This is when he became interested in photography and bought himself an inexpensive Argus camera.

There was more family drama. After a couple of years in California, Erwitt’s father fled to New Orleans to escape alimony payments. He took his 15 year old son with him, but essentially abandoned the boy a year later. How much does that matter? Who can say?

What we can say is that in 1949, at the age of 21, Erwitt returned to New York City, determined to be a professional photographer. He landed a job with a small commercial photography agency and had the good fortune to meet Robert Capa, the famous photographer who helped found Magnum. Capa, perhaps because he identified with the young displaced European immigrant, helped Erwitt get a few photo gigs, including an assignment for the Mellon Foundation.

Just as it appeared his career was going to take off, the Korean War erupted. Erwitt was drafted. Before he left for military basic training, Capa promised him a position with Magnum when he returned. Erwitt was lucky enough to be stationed in France as a photographic assistant instead of an infantryman in Korea. That gave him a lot of experience as a professional photographer. After his two year term of military service ended, Erwitt returned to New York and began work for the Magnum agency.

He soon found himself accepting a wide variety of international assignments, ranging from celebrity portraits to standard photojournalism to photographs for tourism bureaus to fashion shoots. He photographed everybody from President Richard Nixon to Che Guevara to Pope Paul VI to writer Yuko Mishima.

The life of a traveling photographer isn’t often conducive to stable relationships. Erwitt got married and divorced a few times. Is that important information? Maybe. Alimony to multiple ex-wives kept him accepting new assignments.

Perhaps one of the things Erwitt learned in his early life was this: don’t call attention to yourself. He practices that in his work. He prefers to work alone, without much fuss, with minimal equipment. He’s such a self-effacing photographer that he was once ejected from the site of a photo-shoot by one of Annie Leibovitz’s many assistants. He treats photography as a skilled craft, not an art. He’s said the craft of photography is simple.

“I think all photographic assignments are logical problems that have logical solutions. Technique is a myth than can be exploded by reading the literature that’s available…on the Kodak film box.”

That’s the general course of Erwitt’s career–his history. How important is that information? It gives us some idea of what happened to him, when it happened, and where he was when it happened. But it gives us only minimal insight into what shaped his photography, and it tells us nothing at all about why he’s considered one of the masters of photography.

But here, this is important information. On assignment, Erwitt has always carried at least two cameras–one or more for the assignment, and one (usually a Leica) for his personal photography–what he calls his ‘snaps.’ It’s not the number of cameras that’s important; it’s the fact that he draws a bright line distinction between what he does for his job and what he does for personal expression. He shoots photographs as his job; he shoots ‘snaps’ for his personal pleasure, or his personal interest, or his personal curiosity.

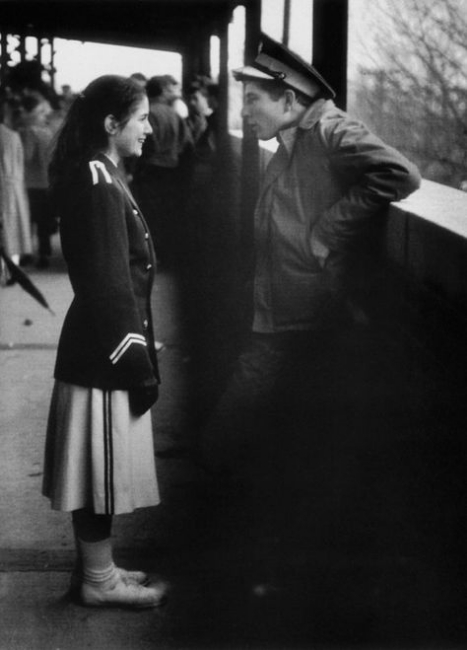

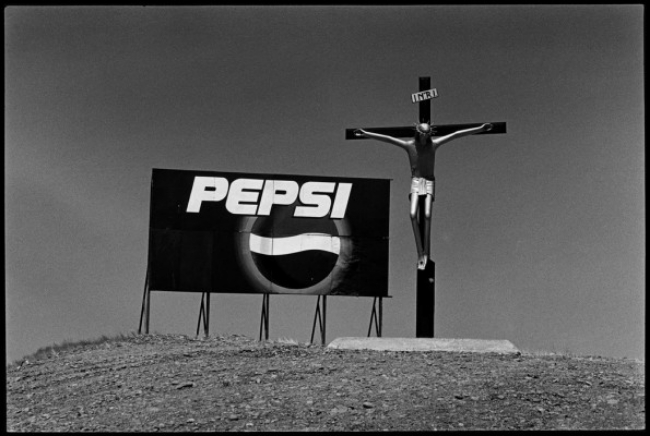

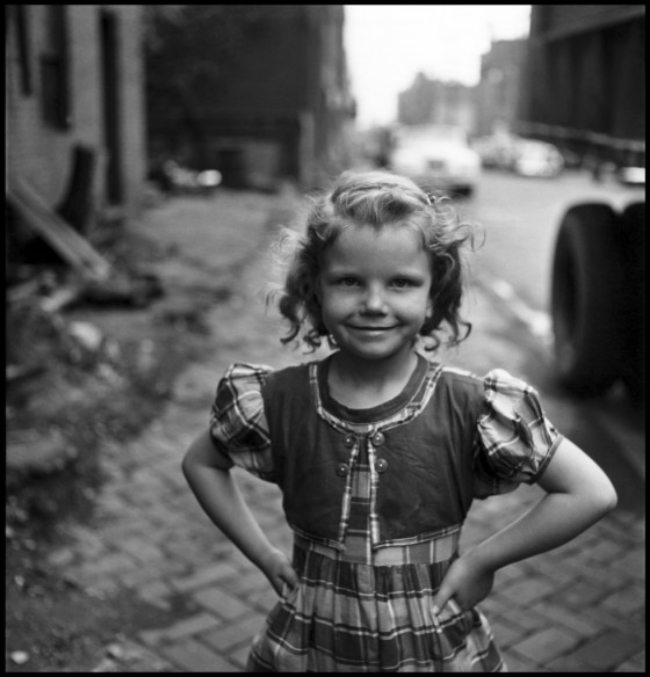

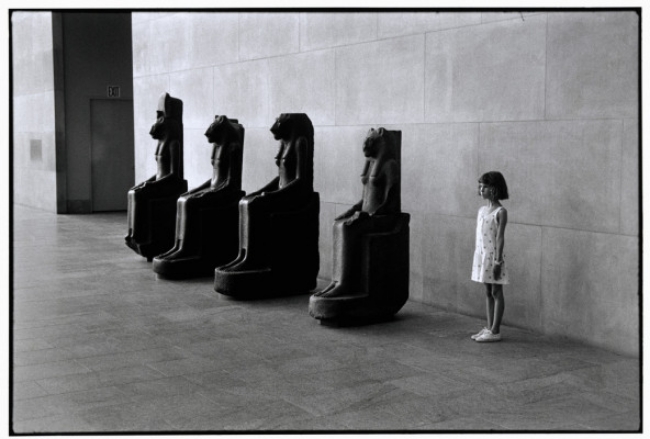

Every photo you’ll see in this salon is one of his ‘snaps’. We’re completely ignoring his professional work. Why? Not because his professional work is uninteresting, but because it doesn’t reveal much of Erwitt as a person (aside from the fact that he’s exceptionally professional). His ‘snaps’ are, I think, a much better indication of Erwitt as Erwitt.

His ‘snaps’ are often charming and witty (he has a special fondness for photographs of dogs), but they can also include powerful socially conscious images. His photographs taken during segregation in the 1950s continue to spark both compassion and outrage.

Erwitt’s ‘snaps’ don’t have reveal a political nor a social agenda, but they’re all marked by compassion. His response to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center is very telling. Like so many photographers, he was in NYC on September 11th. Rather than grab his camera and head for the scene, Erwitt left his camera in his apartment and went immediately to donate blood.

Erwitt has been called the anti-Cartier-Bresson; he’s the master of the indecisive moment, and a purveyor of the non-photograph. “I’ll always be an amateur photographer,” he told an interviewer, referring to his ‘snaps’. Then Erwitt noted that the term ‘amateur’ comes from the Latin term for ‘love.’

Erwitt’s ‘snaps’ reveal him as an artful documentarian. They’re wonderfully expressive and display a generosity of spirit coupled with a pragmatic approach to the scene and an intuitively graceful sense of composition.

Are Erwitt’s ‘snaps’ a reflection of his history? It would be easy to make that argument. His life has been one of dislocation, so it’s not unreasonable to interpret his ‘snaps’ as a search for normalcy; they do show normal moments–whether they’re charming or interesting or distressing normal moments, they’re normal all the same. It would also be easy to interpret his photographs as the world seen through the lens of the constant alien, the person who never really has a home.

I suspect Erwitt would dismiss any attempt to interpret his ‘snaps’ as anything other that artful but casual observations.

“These are just the things you see. You don’t have to look for anything. It’s all there.”

And that may be so. These are just the things you see, IF you have the awareness to see them and the ability to capture it on film. If you’re Elliot Erwitt.

Here’s some more important information about Elliot Erwitt. He’s the only Elliot Erwitt out there.