Debbie Fleming Caffery was born in 1948 in New Iberia, Louisiana on Bayou Teche. She is a product of the intersection of multiple cultures; a woman with an Irish name born in an American town founded by Spanish immigrants in a territory dominated by French settlers who were evicted from Canada and who relied on African slaves for labor while incorporating aspects of African culture into their society. Somehow that peculiar mix of religions, languages, cultures and social norms eventually coalesced into a single and singular community. This is the original lens through which Caffery viewed the world.

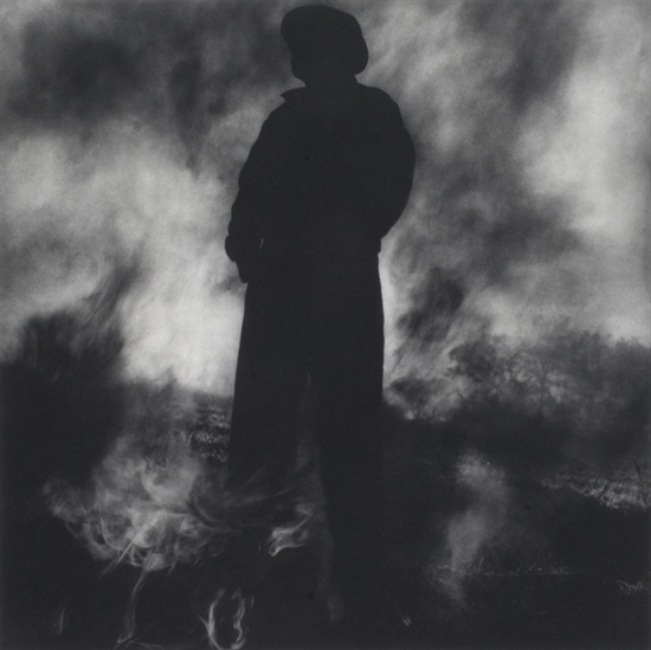

Bayou Teche is cane country. Caffery grew up watching the sugarcane being harvested and processed. In 1973 she began to document it–the cane workers in the fields and in the mills, and especially the harvests. When harvested by hand (as the cane fields of Louisiana were until the mid-to-late 1980s) the field is first set on fire. That burns off the dry, dead leaves (and also kills the spiders and drives off the snakes that live in the cane fields) without harming the stalks and roots. The workers then go in with cane knives – machete-like cutting tools. Because the cane has to be cut just above the ground, the workers must be bent almost double as they hack at the stalks. It’s brutal, back-breaking work–the labor for which slaves were imported. When Caffery shot her photographs the cane harvest was still being performed in much the same way it had been for centuries, and the work was done mostly by the descendents of those same slaves.

Caffery’s images of the cane harvesting are deliberately dramatic. The use of light and shadow transform the figures and the scenery into near-abstractions. The photographs incorporate elements of both documentary photography and fine art; they seem to be balanced halfway between the act of recording the moment and the act of creating art. The pictures seem almost to hint at some primitive relationship between the man, the fire, the earth, and the cane.

She continued to photograph the harvest for years. By the late 1980s most of the cane fields of Louisiana had switched to mechanized harvesting, putting an end to the residual plantation culture, and at the same time putting tens of thousands of unskilled, undereducated laborers out of work.

The style Caffery developed shooting the cane harvests has remained with her through much of her subsequent projects, including what is perhaps her most personal series of portraits: Polly. In 1984, when driving through the nearby town of Breaux Bridge, she noticed a woman emerging from an old ramshackle cabin, a building she’d driven by many times and had assumed was uninhabited.

This was one of those moments that change things. Most people would have continued driving. Caffery stopped and introduced herself. This sort of behavior is less unusual in the American South (at least it used to be less unusual), especially in small rural communities, where people tend to be more willing to speak to strangers. By stopping, Caffery took the first step in what was to be a six-year friendship between the photographer and Polly Joseph.

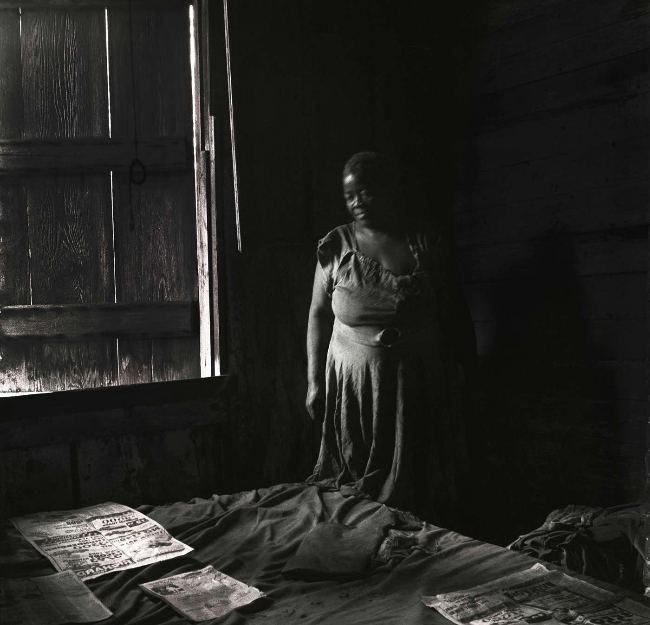

The photographs were generally shot in and around Polly’s cabin. Most of their time together, however, was spent in conversation–just two women talking. “I went there so often and I thought about her so much,” Caffery said. “I would dream about her. I would rather have gone to her house than any place during those years.” Even though the photographs are shot in the same theatrical chiaroscuro style, and with that same balance between documentation and art, they show a tenderness and warmth that’s missing from the sugarcane images.

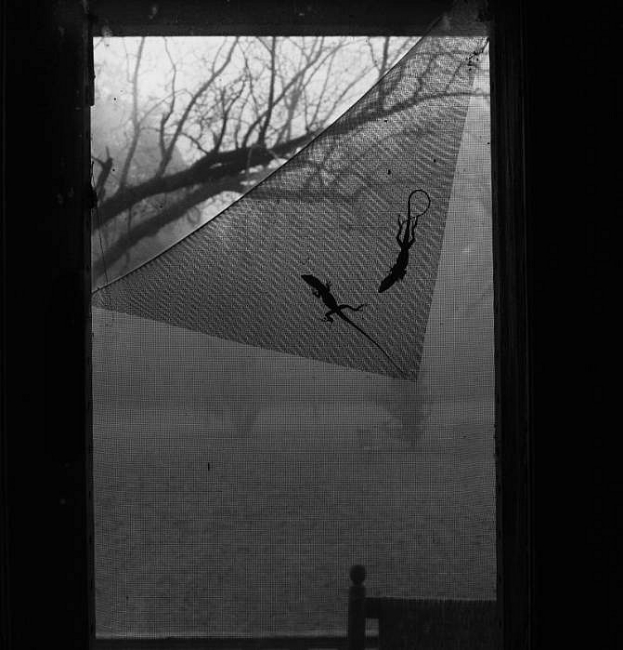

Even when Polly doesn’t appear in the photograph, her solid presence is felt. She was deeply attached to her home, to her community, to her place in the world, and Caffery is somehow able to communicate that. The Polly series reveals a deeply appealing and intense feeling of rootedness in both place and culture. The Polly photographs could be used to support the thesis of Robert Polidori, who claims the rooms in which people live carry strata of meaning and significance that reveal aspects of the people who inhabit them. For example, when we see a pair of baby shoes on Polly’s windowsill and a toy soldier beside them, with the light finding its way through her tattered curtains, we intuit a sense of ongoing personal history.

Eventually, Caffery’s portrait series of Polly Joseph became a touring exhibit and a book. They helped cement the photographer’s career.

Just as her style has remained largely the same, so has her process. Each of Caffery’s projects requires a serious investment of time. They demand a level of commitment.

“The attraction I feel to a subject, whether it be person, animal, situation or place, develops into a relationship that feels like being in love. I spend years on most of my projects; without the major ingredient of time, these intense relationships would be nonexistent.”

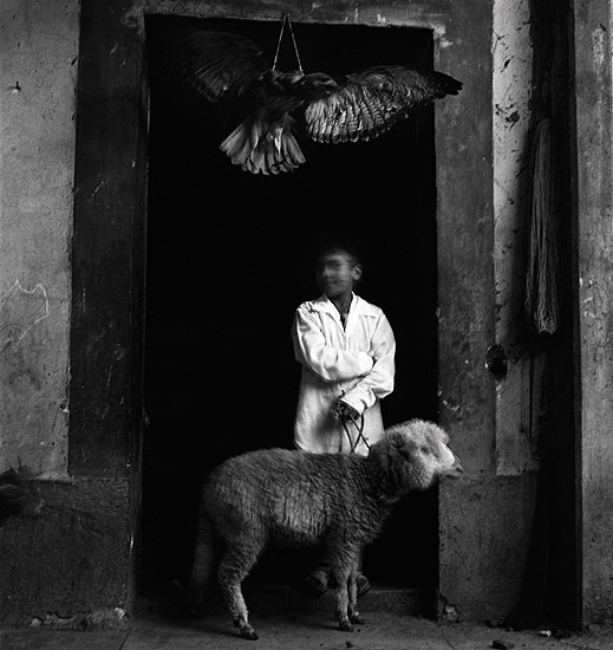

In keeping with her practice of spending long periods of time on a project, Caffery traveled regularly to a small village in Mexico. There she stayed in a small building on the grounds of a Catholic church. Nearby was a small cantina that doubled as a brothel. Although it seems her original purpose was to document village life as it passed through the community’s spiritual center, she felt increasingly drawn to the more earthy passions fostered at the cantina.

“I felt immersed in [the community’s] currents of darkness and light, sin and forgiveness, death and life that flowed in and out of the church grounds.”

Darkness and light, passion and commitment, a powerful sense of community and strong sense of place–whether those primal elements always seem to find their way into Caffery’s work or whether her work revolves around those elements, it’s difficult to say. They certainly contributed to her photographs taken in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Caffery was hired by People Magazine to photograph the evacuees from New Orleans. For a Louisiana photographer whose work so profoundly revolves around notions of community and ties to the land, to see fellow Louisianans uprooted, to see them lose their homes and the things they kept in their homes, to see them treated as refugees and criminals was deeply disturbing. Although there may not be a connection, not long thereafter Caffery moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The curator of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston described Caffery’s work as possessing “documentary roots without documentary intentions.” I’m not sure I can agree with that. I’m more inclined to think her work has documentary intentions that develop beyond the boundaries of documentation. Clearly, she intends to show the world as it reveals itself to her eyes. She may not intend to accurately report the lives of cane workers or Polly Joseph, but she surely intends to communicate how she sees their lives. If her vision and reality aren’t entirely congruent, so be it.

“I am extremely attracted to shades of mystery and shadow, I wait, observe, and listen long enough so that a combination of my emotions and those of my subjects and their environment occur.”

In many ways, the waiting is as central to her work as is her choice of black and white film. The waiting, after all, is another aspect of commitment. Caffery’s work may be in shades of black and white, but it’s informed by a multiplicity of disparate elements combining in unexpected ways. How could it be otherwise, considering who she is and where she comes from?