Helen Levitt has a reputation among art historians and critics. She’s been called “a photographer’s photographer,” “one of the great living poets of urban life,” and “New York’s visual poet laureate.” She’s also been called, sadly but accurately, “the most celebrated and least known photographer of her time.”

Levitt certainly deserves to be better known. She was a street photographer before street photography even had a name. She was photographing graffiti long before graffiti became a popular art form. She worked with Walker Evans on his famous “Subway” series, and although her contribution was more supportive than anything else, it has still been largely ignored. She exhibited color photographs at MoMA two years before William Eggleston’s ‘groundbreaking’ color exhibit there. She has made her mark on photographic history, yet she remains unknown to most outside the insular world of art photographers. It must be said, however, that Levitt bears much of the responsibility for her lack of public recognition.

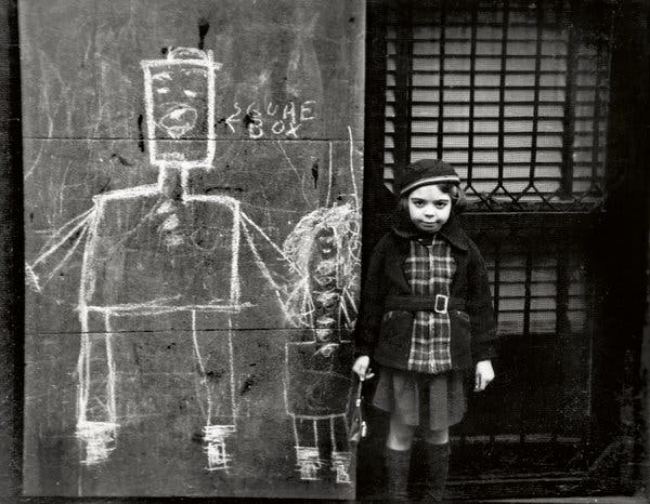

Levitt was born in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn in 1913 to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. Bored with high school, she quit and took a part-time job with a commercial portrait photographer in the Bronx. She also found part-time work teaching art to children in Spanish Harlem. As she walked to work each day, Levitt began to pay more attention to the chalk sketches children made on the streets and stoops and staircases. She decided the sketches ought to be documented, so she bought a camera and began to photograph the street art. Soon thereafter she began to photograph the children who made the art, and then children in Spanish Harlem in general, and later the adults who raised the children.

“I decided I should take pictures of working class people and contribute to the movements. Whatever movements there were—socialism, communism, whatever was happening.”

It must be remembered that a great deal of photography during the 1930s, both in the U.S. and in Europe, was focused on documenting social injustice. Levitt joined New York City’s Film and Photo League, a club for photographers with a social conscience. The club drew many well-known photographers as visitors: Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson.

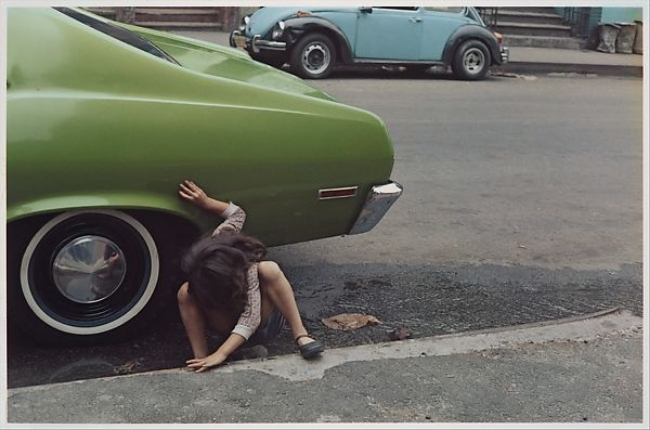

Cartier-Bresson’s visit taught Levitt an important lesson: documentary photography didn’t have to be about social justice. “I realized photography could be an art, and that made me ambitious,” she said. She also learned a great deal from Walker Evans, who would become a friend. He taught her to use a winkelsucher, a right-angle viewfinder. The winkelsucher allows the photographer to shoot sideways so the subject is less aware the camera is focused on him. Levitt’s personal style grew out of the lesson she learned from Cartier-Bresson and the techniques she learned from Evans, as well as her almost pathological reluctance to leave New York City (aside from occasional brief visits to small farms in upstate New York and one trip to Mexico, Levitt has remained in the city).

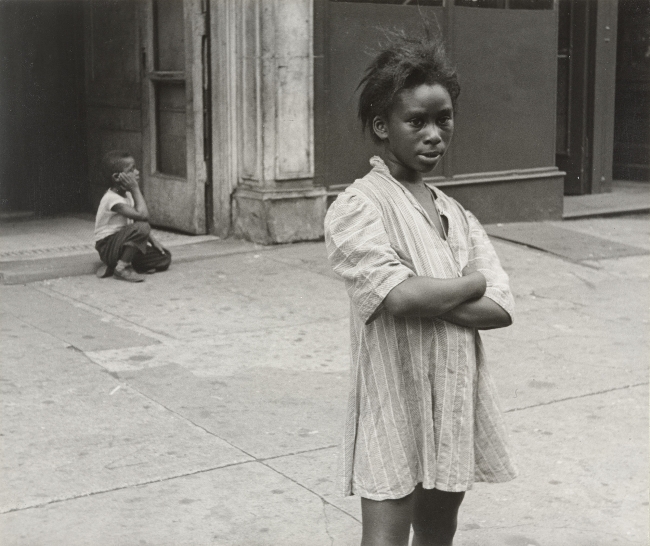

Levitt’s work is almost exclusively urban. Although her photographs are shot outside, we rarely see any elements of nature–little or no sky, no grass, few plants or trees. The vast majority of her work is about people living in lower class neighborhoods of New York City, neighborhoods where much of life had to be lived outside on the tenement stoops, on the sidewalks, on the streets. It’s impossible to look at her body of work and remain unaware of the crushing social effects of poverty, yet her photographs are not political statements. Poverty was simply the environment in which her subjects lived. Levitt’s work is about people and the relationships between people. Even the photographs that don’t actually show people are clearly about the people who are absent from the image.

In 1943 Levitt’s work was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. A couple years later she and writer James Agee began culling photographs for a book to be called A Way of Seeing. The work on the book (and her growing career in still photography) was sidetracked when she and Agee collaborated on a pair of documentary films, one of which (The Quiet One) received an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary. She continued to work in film for the next quarter of a century before returning to still photography. “It was too difficult to try to make film,” she told an interviewer. “You had to get people to work with you, you can’t work alone.”

One of her motivations to return to still photography was the advent of color imagery. “I wanted to try stuff with color,” she said. She got some help in her effort to “try stuff.” In 1959 and 1960, Levitt was awarded Guggenheim Foundation grants to experiment in color street photography. The 1960s proved to be as productive for Levitt as the 30s and 40s had been. The book of black and white photographs she and James Agee set aside in the mid-1940s was finally published, and her color work was said to be exceedingly original. Unfortunately, we’re unlikely to ever see that work. In 1970 Levitt’s apartment on East 13th Street was burglarized; all but a handful of her color transparencies were stolen. Oddly, almost nothing else was taken.

Levitt herself claims not to have any preference in regard to color or black and white film. “Whatever roll of film I have, that’s what I’ll shoot,” she says. Although she appreciates her own photography, she takes a very matter-of-fact approach to it. Levitt allowed one interviewer the opportunity to visit her home–a small 5th floor walk-up. The only photograph to be seen was one clipped from an old magazine: a mother gorilla with her baby. When asked why none of her own work was hung on the walls, Levitt replied “I know what they look like. I don’t want to look at them all the time.” There were, however, a few boxes containing her prints. One box carried the label “nothing good.” Another was marked “Here and There.” Three years later, in 2005, a book of Levitt’s favorite images covering a seventy year span was published. It was entitled Here and There.

For all the emotion in her work, Levitt maintains a rather hard-boiled journalistic approach to the act of shooting. She keeps an unemotional, professional distance between herself and what she photographs. She is only there to record events, not to influence them. Speaking about an image in which a child is crying, clearly in distress, she says “I took it and kept walking.”

In a very real way, Levitt’s approach to photographing children isn’t very much different from that of a wildlife photographer shooting pictures of jackals or leopards or iguanas. The children are creatures whose behavior is only somewhat predictable, whose actions tend to follow certain patterns but whose motivations are often incomprehensible. “I don’t have kids,” Levitt told an interviewer, “and I don’t know people who have them.“

Over time, though, the city changed. Air conditioning became more common, pollution got worse, vehicle traffic increased, and life gradually moved indoors. Fewer people spent time on the stoops or carrying on conversations through open windows. Children stayed inside and watched television rather than playing on the streets. When life in Spanish Harlem left the streets, Levitt left Spanish Harlem. She began shooting in New York’s garment district. “You have to go where something’s going on,” she said.

Despite her pioneering work in color street photography, Levitt has received most of her critical praise for her black-and-white images of children playing. In their book on photography, Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz wrote the following about photographs of children: To be any good, the pictures have to transcend their subject. We never take novels about children seriously unless we can take them as allegories of an adult world. The same strictures apply to street photographs of children.

I’m not sure that applies to the best of Levitt’s work. Her children at play are just children, often playing in ways adults would never countenance or tolerate. Her children in distress are just children trying to cope in a world whose rules and conventions are defined by adults for adults, and enforced by adults. The children in Levitt’s world are precariously balanced between their own independent spirits and the authoritarian oppression of adults. It doesn’t matter if the oppression is conducted by adults in the best interests of the child; what the child understands is how little voice they ultimately have in the matter. Their only recourse is in how they use their imagination.

Levitt’s children use their imaginations theatrically. Much of children’s play, after all, is theater and children always have the lead roles in their own imagination. It’s only natural that they also take center stage in Helen Levitt’s photographs.