Jan Saudek and his twin brother Karel were born in 1935 in the city of Prague in what was then called the Republic of Czechoslovakia. Four years later, Adolf Hitler’s army entered the city. Along with nearly 150,000 other Jews, most of Saudek’s family were sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, where many of them died–some from disease, some from malnutrition or starvation, some after being transferred to the death camp in Auschwitz.

The two young Saudek brothers were interned in a special camp where Nazi doctors, under the supervision of Josef Mengele, studied and experimented on twins. More than 1500 sets of twins were interned in the camp; fewer than 200 individual children survived. Both Jan and Karel Saudek managed to live through the experience.

After the war, Czechoslovakia became a satellite state of the Soviet Union. In 1950, when he was 15 years old, Saudek was enrolled in a technical school to study graphic arts and printing. In the second year of his two year program, Saudek took a class in photography. That lit the spark that would shape the course of the rest of his life. He bought a Kodak Baby Brownie camera (which was eventually replaced by a better Flexaret 6×6, which was basically a Czech-manufactured knock-off of a Rolleiflex) and began shooting photos.

He spent the next twenty years working for the State Printing Works, employed in the service of a government determined to repress or control the personal expression of its citizenry. But his interest in photography and art made Saudek something of a subversive.

His desire to express himself creatively grew exponentially in 1963, when he was able to see a copy of The Family of Man, the book of photographs edited by Edward Steichen. The book, which contains more than 500 photographs by 273 photographers in 68 countries, inspired Saudek to become a serious art photographer, despite the creative restrictions placed on artists by his government.

Saudek became involved in an underground community of artists–writers, musicians, painters, photographers and others who were determined to find ways to express themselves. In early 1968, during a period that became known as ‘Prague Spring,’ these free-thinkers began to demand greater freedom of expression from their government. The government relaxed some of the restrictions, a move that alarmed the Soviet Union. It responded by sending some 200,000 troops into Czechoslovakia. Although artistic speech was again officially suppressed, artists were more determined than ever to find ways to be creative.

Saudek, despite his involvement in the Prague arts community, somehow managed to get a visa for a brief visit the United States in 1969, the year after Prague Spring. He was able to show his work to Hugh Edwards, the very influential Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. Edwards was much taken by the creative authority of Saudek’s work, especially considering the political climate in which he was forced to work.

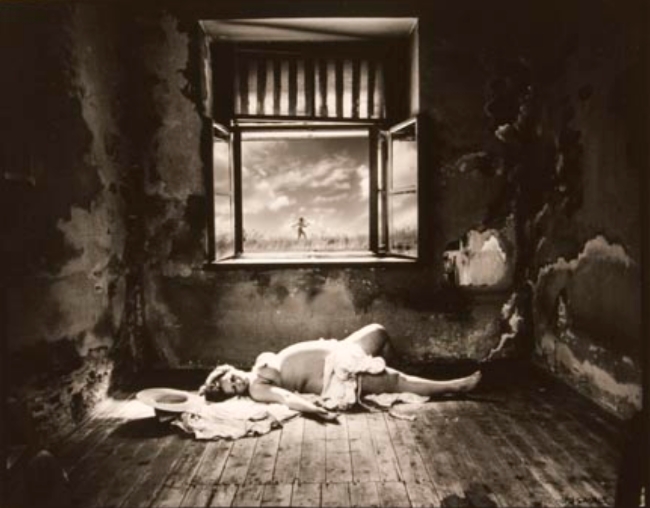

Not long after he returned from the U.S. Saudek’s wife, fed up with his frequent infidelities, kicked him out of their house and later divorced him. Saudek found himself impoverished, living in grungy cellar, under suspicion of subversive expression by the Czech Secret Police. He owned little except for his clothes, the old bicycle on which he rode back and forth to his job as a printer, and his Flexaret. For the next seven years, those miserable conditions led to Saudek’s most creative period. The mottled cellar wall which served as a background for so many of his photographs has become an iconic and immediately recognizable aspect of his work.

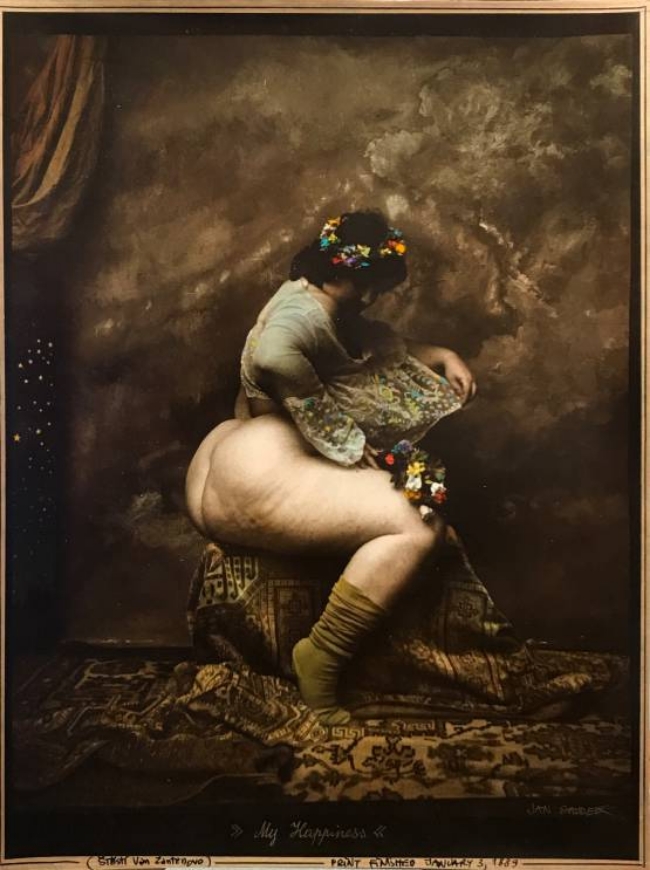

Beginning in the late 1970s, Saudek began to hand-tint many of his black-and-white photographs so that they evoked the tone of 19th century erotic postcards. This resemblance was further enhanced by his use of large women as subjects, either nude or clad in skimpy lingerie…a common theme found in such postcards. As Saudek’s reputation grew among the Prague artistic community (and, slowly, to the Western art world), the eroticism of his work increased. So, for that matter, did his reputation as the ‘bad boy’ of the Czech art world. Saudek eventually became as well-known for his lurid, womanizing lifestyle as for his photography.

During the 1970s and 80s, many of Czechoslovakia’s artists were threatened, silenced, intimidated, imprisoned, or sent into exile. The artistic community survived in part through samizdat, the practice of disseminating artistic works…writing, music, photography, painting…through self publication and underground distribution.

By 1984, Saudek had become famous enough that the government permitted him to quit his job in the State Printing Works and granted him a permit to work as an artist. They nevertheless continued to monitor him and his work. In 1987, the Secret Police seized all his negatives. Although they later returned them, the move was clearly intended as a warning to Saudek as well as other artists. Saudek, predictably, essentially ignored the warning.

In 1989 everything changed. Czechoslovakia peacefully shifted from a Communist satellite state to an independent democracy. In 1993, the nation separated into the Czech Republic and the nation of Slovakia. Saudek’s work began to gain popular and critical attention in both Europe and North America. His images even began to be used as cover art for pop and alternative rock groups like Soul Asylum and Beautiful South. His style of photography influenced the video for REM’s Losing My Religion.

The shift in the political climate was reflected in Saudek’s work. He left his cellar and began shooting photographs outside again. He even returned to the site of his most famous photograph, Hey Joe, the banks of the Vlatva River. Where his early photograph was black and white, and full of the rebellious sort of spirit seen in the 1953 American movie The Wild One, his later image is soft and romantic, featuring a nude curly-haired blonde walking peacefully toward a flock of swans. The later photograph lacks the power and the desperate yearning of the earlier image, but it reveals the trend of Saudek’s work.

In 2007, photographer Adolf Zika released a documentary film about Saudek, appropriately titled Jan Saudek – Trapped by his Passions, No Hope for Rescue. Said Zika, “Jan will always want more. He has enjoyed his passions, but of course there is always a price. You can’t indulge as much as Jan has and not pay the price.”

The question, of course, is this: what price? What price has Saudek paid for his art? What price has he paid for his success? The collapse of the Soviet Union and the repressive Czech government has given Jan Saudek both a level of fame and tremendous commercial success. Where his work was once suppressed, it is now widely available. Where it was once rebellious and subversive, it is now commercial and increasingly bland. Where his early work was filled with dark grotesqueries and mercurial tension, it is now predictable and pretty.

At one point in Zika’s documentary, Saudek is seen musing over the question of whether “it’s all worth it.” One certainly can’t begrudge Saudek his success. He worked for it and suffered for it, and if his motives were a bit (or more than a bit) selfish and arrogant, that doesn’t make him much different from many other artists. At the same time, though, one has to wonder if creative freedom and commercial success has hurt him as an artist. Assuming his early work was better (and that, of course, is a matter of opinion), did Saudek need to be working against a repressive regime in order to be his most creative? Did he need the tension of suppression in order to release his creativity? Did he need a certain level of misery in order for his imagination to escape?

There’s no answer to those questions, of course. But unanswerability seems to be the nature of most important questions.