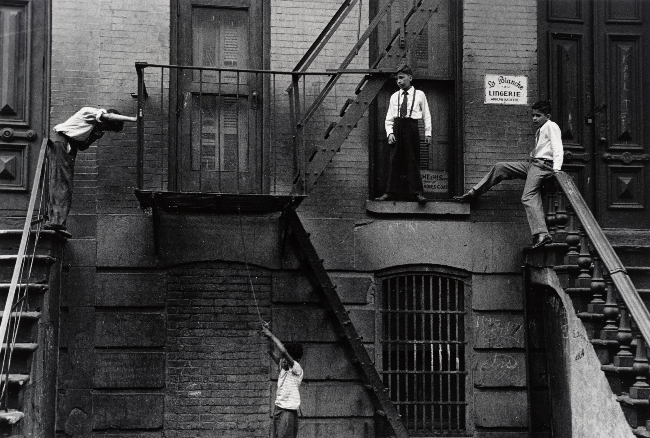

I can’t say the photograph below was the first photo I saw by DeCarava, but it’s certainly the first of his photographs that I remember. More accurately, it’s the first of his photos that I’ve never forgotten.

DeCarava had this to say about that photo:

“Even though it jars some of my sensibilities and reminds me of things that I would rather not be reminded of, it is still a good picture. In fact, it is good just because of those things and in spite of those things.”

I didn’t know the photograph was by DeCarava when I first saw it. In fact, I’d never even heard of Roy DeCarava. But there was something so raw about the photograph, something so dark and passionate, something both beautiful and grotesque about those two contorted figures, that I’ve never forgotten the image. It wasn’t until I began researching DeCarava that I discovered he was the photographer.

DeCarava has said he finds that photograph “very hard to live with.” He shot it in 1951, during the intermission of a show at a Harlem club. The two men are dancing…

“…in the manner of an older generation of black vaudeville performers…their figures remind me so much of the real life experience of blacks in their need to put themselves in an awkward position before The Man…to demean themselves in order to survive, to get along.”

DeCarava was born in Harlem in 1919, an only child raised by a single mother (his parents separated soon after his birth). As a child he worked a variety of odd jobs—shoeshine boy, ice carrier, newspaper boy—to help his mother. In 1938, after graduating from high school, DeCarava won a scholarship to the Cooper Union Institute, one of the most selective colleges in the U.S. There he studied painting for two years. Because of the prejudice and discrimination he encountered there, DeCarava left Cooper Union and began studying painting and illustration at the Harlem Art Center.

In 1943 he did a brief stint in the Army as a topographical draftsman, but was granted an early medical discharge. He returned to Harlem and found work as a commercial illustrator and printmaker. He continued to sketch and paint. In 1946 he decided to buy a 35mm camera, partly to capture ideas for his painting and partly to document the artwork itself. As might be expected, the purchase changed his entire approach to art.

By 1949 photography had become DeCarava’s primary artistic form of expression. He had his first major exhibit the following year: 160 prints. That’s right—one hundred sixty. Three of them were purchased by Steiglitz for New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

In 1952, DeCarava was the first African-American to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. US$3200, a sizable sum of money in those days. The average income in the U.S. was only $3500 and you could buy a gallon of gas for 20 cents and a new car to put it in for less than $2000. That money allowed him to devote an entire year to photographing his community. In his application for the Guggenheim grant DeCarava wrote:

“I want to photograph Harlem through the Negro People. Morning, noon, night, at work, going to work, coming home from work, at play, in the streets, talking, laughing, in the home, in the playgrounds, in the schools, bars, stores, libraries, beauty parlors, churches…I want to show the strength, the wisdom, the dignity of the Negro people. Not the famous and the well known, but the unknown and the unnamed, thus revealing the roots from which spring the greatness of all human beings.”

And he did. He surely did. He photographed it all, for an entire year. And at the end of that year, he discovered that nobody cared. Publishers rejected the work.

It wasn’t until 1955 that DeCarava’s work found its way into print. The publication of The Sweet Flypaper of Life was made possible in part by the help of poet-playwright Langston Hughes, who wrote the text accompanying the photographs. The book, which was described as “achingly beautiful,” brought DeCarava the attention he deserved.

In a way, those early years are a fractal view of the pattern of DeCarava’s life; hard work which is ignored, followed by hard work which is rewarded, followed by hard work which is ignored. followed by…you get the point.

“I was famous, then I got buried, then I was famous again, then I got buried again and then I was famous again.”

He continued to work as a commercial illustrator until 1958, when he was able to support himself as a freelance photographer. But it wasn’t until 1975, when he was offered a position at Hunter College, that DeCarava was free to put his own work first.

One thing remained consistent throughout DeCarava’s career: he worked hard at his photography. When his work was recognized and appreciated, he kept on shooting. When his work was going unrecognized, he kept on shooting. He refused to compromise on the artistic integrity of his photographs.

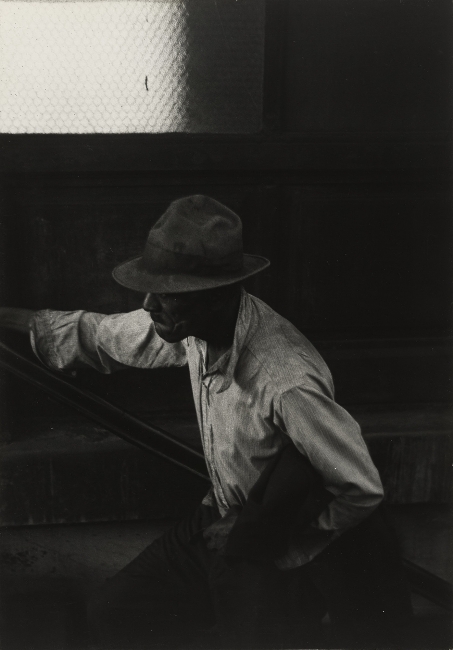

DeCarava’s style is noteworthy for three things: the intimacy of his images, his absolute reliance on ambient light, and his predilection for dark, dark prints. By concentrating his eye on the neighborhoods in which he’s lived, DeCarava brought an indigenous familiarity to the photograph. Whether he was photographing a famous jazz musician or a weary workingman climbing up out of the subway, there is something in the image that suggests an almost familial affection. Despite that gentleness, DeCarava never turns away from the uglier aspects of life in Harlem or Bed-Stuy; he simply incorporates them as part of the reality of the situation.

Because he wants to represent reality in an artful way, DeCarava has always insisted on using natural light. He feels flash photography in real life situations is an intrusion. It disrupts. Besides, he’s apparently been in love with light and shadow since he studied the paintings of Rembrandt in college.

That insistence on natural light often results in negatives that are dark, obscure, a tad blurred. When printed, they produce images that are equally dark and obscure, sometimes to the very edge of legibility. Decarava’s darkness is always full of suggestion, a sense that there is more to be seen, something more to be understood. He dodges and burns, coaxing hints out of the deep shadows and obnubilating unwanted detail in the light. He has been known to print, reprint, and reprint again and again—a long process of trial and error—for up to a year to get an image just right.

DeCarava can sound at times like a very angry man. He may, in fact, be an angry man. But his work doesn’t feel driven by anger. My sense is that it’s not even driven by a need to document the lives of a marginalized or oppressed community. DeCarava’s work seems driven primarily by a desire to make art. If that art reveals something about marginalized, oppressed lives, that’s because that’s just how it is.

DeCarava wasn’t the first African-American photographer to shoot life in Harlem and Bed-Stuy, but he was the first to do so without any political or social agenda. Until he came along, photographers working in African-American communities tended to view the people living there through a sociological or political lens. They treated the neighborhoods and the people living in them as material for creating powerful images that would inspire social change. DeCarava treated his world as a location in which art exists. His photographs don’t show a community in a constant state of siege and trauma; his photos show ordinarily lives of ordinary people transformed into art.

Roy DeCarava lives quietly and anonymously in the Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn. He remains on the faculty of Hunter College. In 2006 he was presented with the National Medal of Arts by President Bush at the White House. DeCarava neglected to mention the honor to his colleagues at the college. His neighbors are unaware of his accomplishments. “I don’t think they even know who I am on this street. I’m just the old man who lives next door.”

He will be 90 years old this week.