People who live in northern climates have a different relationship with the landscape. The reality of four very distinct seasons gives the natural world four very different faces, one for each season. Photographer Beth Dow, on the other hand, sees a fifth face. The face of those quiet, interstitial periods between seasons. More specifically, between fall and winter and between winter and spring.

Dow, born and raised in Minnesota, is intimately familiar with that mid-seasonal interlude when autumn subsides into winter and winter flows into spring. Much of her photographic career as a landscape photographer is grounded in those two brief periods of time. Dow has described those transitional weeks as ‘precarious’ because that’s “when everything hangs between life, death, and life again.”

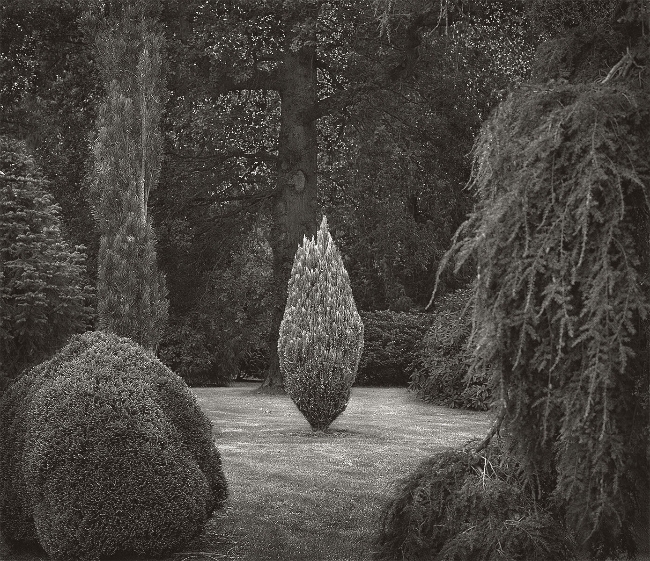

There is something stark and nakedly truthful about the transitions into and out of winter. There are few leaves to camouflage the shapes of trees, few bright colors to distract the eye, fewer soft shapes to lull the senses. Everything is almost exactly as it is, revealed as honestly and simply as is possible through the second-hand vision of the camera lens and the third-hand revelation of the photographic print.

Dow openly acknowledges that what her audience sees in the final print isn’t an accurate representation of what she saw at the time she shot the photograph. Indeed, the print doesn’t even correspond exactly with what she saw through the viewfinder. Dow shoots with both a 35mm SLR and a medium format camera, then crops the final images square (or near square).

The natural landscape is expansive, of course. Dow’s landscapes, like that of all landscape photography, is necessarily restricted and narrowed, including only those elements she finds most compelling. And therein lies the source of artistic tension: Dow deliberately opts to photograph her landscapes during the most straightforward and visually simple time of year, deliberately using formats that will include extraneous and distracting details, then just as deliberately removes those details–all with the motivation of producing an emotionally honest visual experience.

And I think she succeeds.

The manipulation of Dow’s images continues in the darkroom. Her photographs are printed at her direction by Keith Taylor (a photographer and printmaker who has also printed work for noted photographers such as Alec Soth; he is also, conveniently, her husband). She routinely burns and dodges the image to direct the viewer’s eye to specific aspects of the landscape. One result of that is a tight image; everything in the frame–every shadow, every limb, every shape–is there because she wants it there.

“My images are not depictive. I use the land before me as a jumping off point, implying light or shadow where perhaps there was none, as a way to create my own path through the garden.”

The concept of the garden figures heavily into Dow’s aesthetic. Humans have been engaged in decorative gardening for at least 3500 years. All gardens are an attempt to impose a sort of order on the natural world, and the natural world resists all attempts at gardening. By shooting her photographs in those in-between seasons–a time when gardens are balanced between the control of the gardener and ungovernable nature–Dow inserts another degree of visual tension into her work.

“[M]ost people love gardens for their beauty. I’m seduced by something else entirely, and my favorite landscapes are overgrown, shaggy, and a bit off their game. Gardens attempt to control and dominate nature, but nature resists – it bolts, leans, withers, and isn’t as malleable as we pretend.”

In her series entitled In the Garden Dow appears to rely heavily on the artistic landscape traditions of 19th and early 20th century photographers (such as Eugène Atget). Like Atget, her landscapes tend to be unpopulated. She rarely includes people in her compositions. Yet the presence of people is palpable.

The people in Dow’s work are present in the ways they shape the landscape. They’ve trimmed, they’ve pruned and sheared, they’ve shifted ground from one place to another, they’ve planted and replanted, they’ve burned. They’ve added benches, removed unwanted saplings, inserted new plants, reshaped the existing plants, laid down flagstones, dug up natural stones. They have deliberately molded the landscape to suit their own aesthetic tastes.

They’ve also influenced the landscape unwittingly, through carelessness or neglect.

Dow considers herself a different sort of gardener. “[B]y positioning the lens, cropping my prints, and using dodging and burning to guide he viewer’s eye through a picture, I feel that I too am a gardener in a sense.” Her relationship with her image is similar to that of the gardener’s relationship to the garden. The act of creation is pleasing in and of itself, but the greatest pleasure comes when the work is appreciated by others.

Fine art landscape photography is a rare skill. The landscape is there all the time, available to anybody with a camera. To take what is visible to all and refine it, to distill it into an artful and compelling image requires more than mere imagination; it also requires a sort of reductive inventiveness due to the limitations of the lens. It takes the ability to see less than what’s there, and make that ‘less’ complete in itself.

I have said before (and been duly chided for it) that I’m not much of a fan of landscape photography. Although I find it visually appealing, I rarely find it intellectually stimulating. There are exceptions, however, and Beth Dow is one.