Henryk Ross was born in Warsaw in 1910. Up to a point, he lived a relatively normal life. He went to school, graduated, took a job, got married. He was lucky in many ways; he worked at a job he enjoyed (a sports and general news photographer) in a city he loved. Under normal circumstances, he’d probably have made a decent living, had kids, grown old, retired and told his grandchildren funny stories about being a news photographer.

But by 1939 there wasn’t anything remotely normal about being a Jew in Poland. Nazi Germany invaded and conquered the nation in a matter of weeks. By the end of 1939, a number of anti-Jewish ordinances had been enacted; Jews were stripped of their homes and possessions, forced to wear yellow stars as a means of identifying themselves, and forcibly relocated into ‘temporary’ resettlement camps.

One of the largest of these was the ghetto in the city of Lódź. By May of 1940 more than 160,000 Jews were living in the Lódź ghetto, an area of just four square kilometers—only half of which was developed and habitable. The ghetto was a closed community, surrounded by walls and barbed wire fences and German guards. Inside the walls the community was governed by a Jewish Council appointed by the Nazis. The duty of the council was to maintain order and to insure the inhabitants of the ghetto were industrious in manufacturing goods for consumption in Germany. The Jewish Council maintained its own policing unit clothed in uniforms designed and produced by their own people.

Henryk Ross was one of the lucky few. He had a skill the Nazis could put to use—photography. They wanted a photographic record of daily life within the ghetto, documentary material they could distribute to the world through agencies such as the Red Cross to demonstrate to the world that the people they’d interned without trial were being treated humanely. In other words, they wanted somebody to help them hoodwink the world.

Ross accepted the assignment. Refusing to accept it, of course, would have been extremely unwise. He was given a camera and film, and set to work for the ghetto’s Department of Statistics. For the most part, he photographed those Jews who’d agreed to assist the Nazis in running the ghetto: the administrators, the policing agents, members of the Jewish Council—the ‘elite’ who ran the day-to-day operations of the ghetto. The Nazi public relations machine wanted to document contented families, happy workers, religious ceremonies, weddings, and well-fed children gamboling at family gatherings and picnics.

Ross gave them that. Looking at these photographs, it must be remembered that Henryk Ross not only photographed the Lódź elite, he was one of the elite. His work spared him from the worst of the conditions suffered by the majority of people living in the ghetto. Like many others who collaborated with the authorities, Ross secretly labored to undermine the very people for whom he worked. In addition to shooting the photographs the Nazi party officials wanted, Ross also shot photographs he thought were important. He photographed the men and women who were being slowly worked to death, he photographed the under-fed and starving, he photographed the disobedient and noncompliant who were executed. He shot those images at great risk to his own life. Even so, it cannot be denied that Ross and his wife benefited materially as a result of his work.

Overcrowding within the ghetto, obviously, was a serious issue. Even though thousands died due to disease and starvation, the population of the Lódź continued to swell as Jews from other areas arrived. In December of 1941, the Jewish Council of Lódź was ordered to select 40,000 people to be relocated. Other similar “relocation” orders soon followed. Within a few months, it became obvious to the people living in the ghetto that people weren’t being relocated; they were either being moved to death camps or murdered outright. Despite that knowledge, the Jewish Council continued to obey each order to select members of their community to be “relocated.”

By the summer of 1944, with Germany certain to lose the war, high ranking members of the Nazi Party decided it was time to liquidate the remaining population of the Lódź ghetto. Ross, who had been spared from the relocation process because of his work, saw the end coming.

“Just before the closure of the ghetto in 1944, I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy—namely the total elimination of the Jews from Lódź by the Nazi executioners. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom. I hid them … in the presence of several of my friends, so that if we died and one of us survived, the photographs would remain for the sake of history.”

Ross buried up to six thousand negatives. He and his wife were among the last Jews remaining in the ghetto, tasked with ‘cleaning up’ anything left behind by ‘relocated’ Jews that might be useful or valuable. They knew they were to be killed when the task was finished. However, in January of 1945 the Soviet Army arrived and liberated the ghetto. Ross and his wife were among the 877 Jews known to survive.

A couple of months after the liberation, Ross dug up the negatives he’d buried. Water had infiltrated the containers in which they’d been buried, and many of the negatives were damaged or destroyed. He saved what he could and brought them with him when he and his wife emigrated to Israel. There he put them aside until 1961, when Adolf Eichmann (one of the chief architects of the Holocaust) was captured and put on trial. Ross offered the prosecution photographic evidence of the crimes committed in Lódź. His evidence and testimony helped convict Eichmann.

Despite that, Ross didn’t really organize or catalog his negatives until 1987, four years before his death. He was apparently reluctant to display the images because so many of them show seemingly happy, well-fed Jews engaged in ordinary activities. Ross was concerned such images might complicate the tale of the ghetto by suggesting the extent of Nazi cruelty wasn’t as extreme as it truly was.

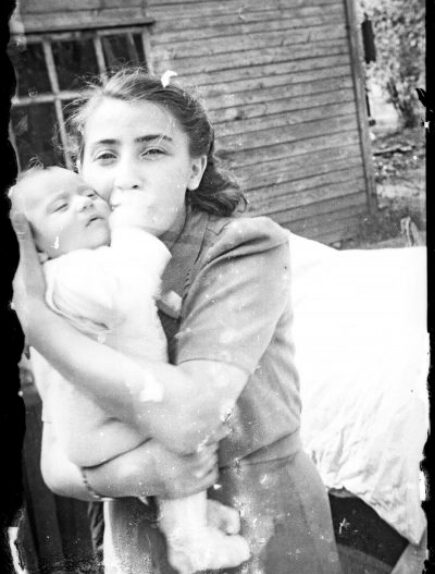

In fact, it’s impossible to look at these photographs objectively. It’s almost a certainty that every single person depicted in them was killed before the end of the war. The mother kissing her child, the young man carrying the Torah scrolls, the cheery chubby boy dressed in a miniature “ghetto police” uniform—all dead, collaborators and resisters, parents and children, privileged elite and ordinary person, all dead.

For four years—1940 to the end of 1944—Henryk Ross documented events that are almost beyond comprehension. In those four years, more than 200,000 Jews were interned in the ghetto of Lódź. Of those, only around 10,000 survived, even after being transported to labor or death camps. How can a person photograph a faux sort of ‘normality’ in circumstances that are as far from normal as humanly possible, and still retain a sense of what ‘normal’ means? How can a person bear up under the guilt of collaborating with his oppressors, even if that collaboration was mitigated by his efforts to record that oppression? How can we look at these photographs and not ask ourselves how we might behave under the same circumstances?

Looking at these photographs, we must remind ourselves that each one—each individual image—is evidence of a unique life. Each of these people existed. For many of them these photographs are the only extant record of that fact. There are no family memories of many of these people, because no family members were left alive. There are no graves to be visited, and nobody to visit them if the graves existed.

In that sense, these are not just photographs; these are epitaphs.