Who knows where art comes from?

Surely, it must be influenced—if not actually shaped—by the artist’s life experience. In Japan, there was a generation of artists born before the Second World War, who grew up during that war, and who began to make art in the weird period after the war. It’s difficult to grasp the extent to which that war shaped modern Japanese culture. The complete and utter defeat of their military, the near-total devastation of nation’s major cities through firebombing, the detonation of two nuclear bombs, the abject surrender to a foreign power, the abdication of the Emperor, the subsequent military occupation of the nation by the enemy, the new foreign laws imposed on the populace by that military—all of these circumstances combined to shatter what had been an insulated, tradition-bound, and largely homogeneous society. It wasn’t just Japan’s infrastructure that was destroyed during the war; it wasn’t just their cities and their economy; their understanding of who they were as a nation and as a culture was also damaged.

Toshihiro Hosoe was born in the town of Yonezawa in 1933. His father was a Buddhist priest; in 1940, his father was given duties at the Shirahige Shrine in Tokyo. The family lived there until 1944, when the city became the target of the Allied firebombing campaign. Hosoe and his family were evacuated to the countryside. There, he heard folk tales about the yōkai—strange beings and supernatural creatures. Yuki-onna, the snow woman; the mischievous kitsune, the fox; the tengu, often depicted as bird-like beings who can take on a humanish form (the creatures which later came to fascinate photographer Masahisa Fukase). What child wouldn’t be enthralled—and, perhaps, a bit frightened—by such stories? These folktales stayed with Hosoe, and would return to him later in his life.

The family returned to what was left of Tokyo in September of 1945, only a month after the nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Japan surrendered. Over half of the city had been destroyed in the firebombing, between 130,000 and 300,000 people had been killed, more than a million were left homeless. Tokyo was under military occupation and would remain so for the next six years.

Four years later, 16-year-old Hosoe was an active member in his school’s English language club and in the photographic society. His most common photographic subjects were the American children who lived in military housing—a neighborhood built on the ashes of old Tokyo called Grant Heights. He won a prize in a Fuji photo contest for a portrait of a young American girl. At the suggestion of a cousin, Hosoe abandoned his name Toshihiro and adopted “one more suited to the new era“: Eikoh (perhaps in reference to Dwight ‘Ike’ Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the US military).

After graduating from the Japanese equivalent of high school, Hosoe enrolled in the Tokyo College of Photography. He joined the ‘Demokrato’ artists’ group and had his first exhibition: An American Girl in Tokyo. He eventually began working as a freelance photographer shooting largely for women’s magazines.

As he grew older, his fascination for American culture waned and he began turning his camera on Japanese subjects. By the late 1950s, Hosoe began “thinking deeply about the meaning of being Japanese.”

His 1960 exhibition, Otoko to Onna (Man and Woman), was something of a defining moment for Hosoe. The black-and-white photographs were considered to have a more distinctly Japanese sensibility. Many of the photos featured his friend Tatsumi Hijikata, the originator of the Butoh dance movement—a sort of conceptual ‘anti-Western’ form of dance that often revolves around topics of death, decay, ghosts and taboo modes of sexuality. Hijikata’s first major butoh work was based on Kinjiki, a novel by Yukio Mishima—the popular and controversial writer.

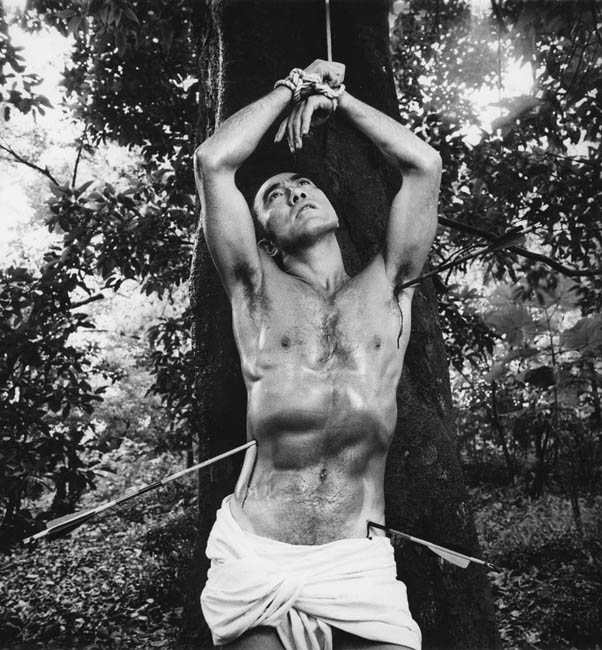

That next year, 1961, when it came time for Mishima to have his portrait taken for the jacket of a book of essays, he asked for Hosoe. When they were introduced, Mishima said, “I loved your photographs of Tatsumi Hijikata. I want you to photograph me like that.” What was originally intended as a simple portrait turned into a project—ten photo sessions of a period of six months. The final images were dark, sensual, dreamlike; Mishima loved them. The exhibition and subsequent book were entitled Barakei, which according to Hosoe, is literally translated as “punishment of roses.” Barakei not only solidified Mishima’s reputation as a controversial figure of the arts), it also established Hosoe as one of Japan’s leading contemporary photographers. A decade later, Mishima committed seppuku, a form of ritual suicide by disembowelment.

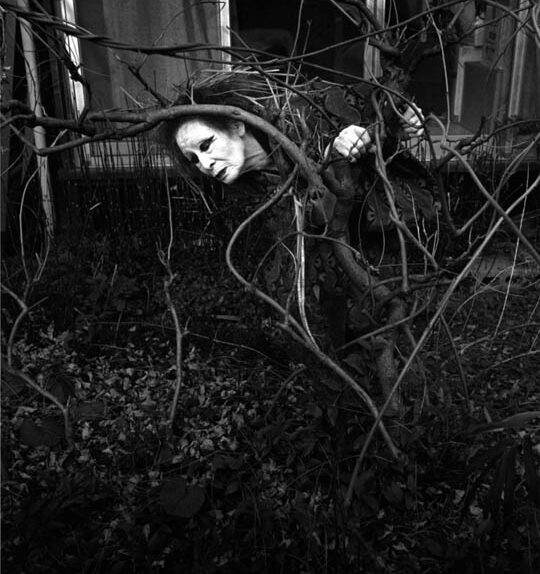

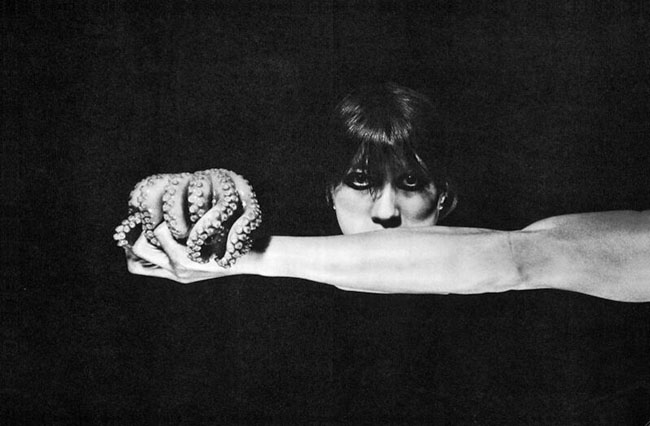

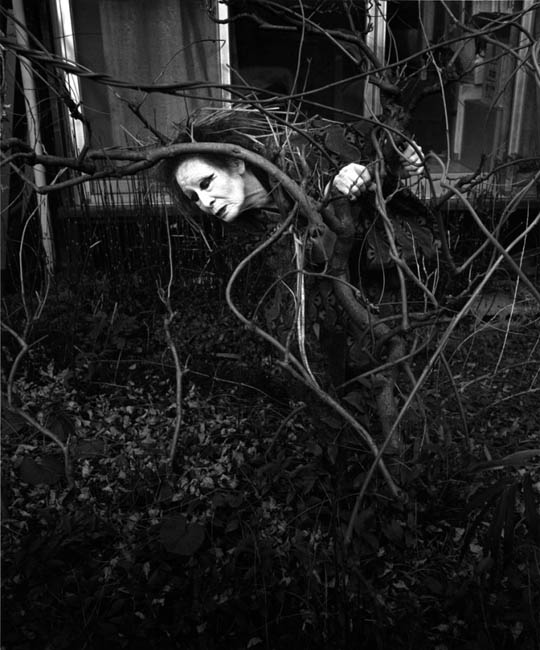

In the wake of the initial success of Barakei, Hosoe began a project using his friend Tatsumi Hijikata, the butoh dancer. The project was based on the yōkai, the supernatural creatures from the folktales he learned while he and his family were avoiding the firebombing of Tokyo. More specifically, the project focused on kamaitachi—sharp-clawed, clever, arbitrarily vicious creatures thought to resemble weasels. The kamaitachi travel on the wind, moving through the countryside, stalking and threatening farmers and their children. The result was a series of disturbing but beautiful images depicting the illusive mythical creatures.

“The camera is generally assumed to be unable to depict that which is not visible to the eye, And yet the photographer who wields it well can depict what lies unseen in his memory.”

Hosoe’s affiliation with butoh led to his longest project, the Butterfly Dream. The title is a reference to parable of the Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi, in which the sage dreams that he is a butterfly and, upon waking, wonders whether he is not in fact a butterfly dreaming he is Zhuangzi. For more than four decades, Hosoe photographed butoh dancer Kazuo Ohno. The dance form takes its name from the Japanese ankoku butō, which translates as ‘dance of darkness’. It was created as a post-war response to the refinement and understatement of traditional Japanese aesthetics. It’s performed in white body makeup, with hyper-controlled motion, grotesque costumes, clawed hands, rolled-up eyes.

Fifteen years after the end of the war, Hosoe began trying to understand what it meant to be Japanese. It took that long for him to even frame the question. His attempt to find an answer has been played out, in part, through his photography. Through his art.

Where does art come from? For Eikoh Hosoe, it seems to come in part from the awareness that there are things you can’t see or understand, things that can, without warning, ride into your life on the wind—things like an atomic bomb or a kamaitachi—and leave you broken and bleeding, but still beautiful.