Robert Frank is, and always will be, best known for The Americans, a work that’s shaped modern photography. But despite its startling originality, that book didn’t just spring up out of nowhere; it was molded by the circumstances of Frank’s life—by his childhood, by the culture in which he was raised, by his professional training, and by his early career as a photographer. Although The Americans was undoubtedly the highlight of his career, it wasn’t the culmination of it. There is more to Robert Frank than those two years in the middle 1950s. Much more.

He was born in Zurich, Switzerland in 1924 to a wealthy, business-oriented Jewish family. His was a relatively privileged childhood, at least in terms of the trappings of luxury. Financial stability, however, couldn’t relieve the anxieties of being a Jew in Europe during the Second World War. Switzerland’s neutrality theoretically protected the Frank family, but Swiss Jews remained understandably concerned that the German Army might not respect Switzerland’s nonaligned status and invade nonetheless. Those concerns were exacerbated by Swiss anti-semitism, which was further amplified by Hitler’s speeches being broadcast on Swiss radio. To make matters worse, although Frank’s mother was a Swiss citizen, his father—and therefore the Frank children, Robert and Manfred—were German citizens. When Hitler issued an edict rescinding the citizenship of all German Jews, Frank (along with his father and brother) were rendered stateless, making their continued residence in Switzerland all the more perilous.

In addition to all those sources of angst, Frank also experienced the usual emotional traumas of being a teenager. He rebelled against what he saw as his family’s all-absorbing interest in money and materialism. When it came time for him to consider a career, Frank rejected the family business and entered an unpaid apprenticeship program in photography—unpaid because only Swiss citizens were eligible for paid apprenticeships. The program was classically Swiss—very regimented and very pragmatic, concentrating on the fundamental elements of photographic craftsmanship (mixing chemicals, darkroom techniques, memorizing exposure tables, etc.). He was also trained in the philosophy of New Photography (or Neues Sehen) movement—a stylistic and theoretical approach that espoused clarity, sharp focus, ‘truthfulness’ of the subject matter, and placed a heavy emphasis on producing specific tonal qualities in the print.

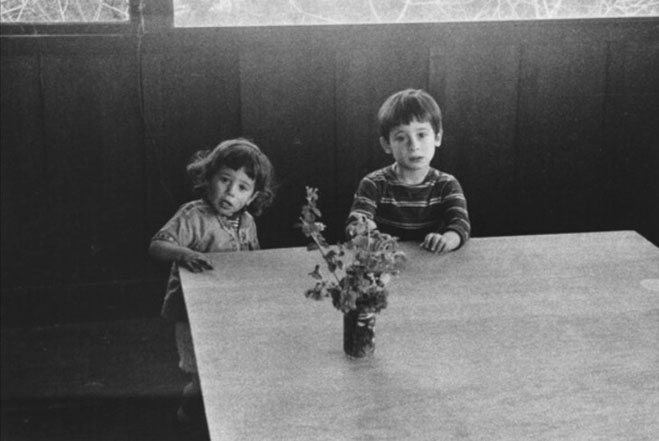

The end of the Second World War coincided fairly closely with the completion of Frank’s apprenticeship. In 1947 Frank, at age 22, set out for New York City. On the strength of his apprenticeship portfolio, he obtained a position as a studio photographer for Harper’s Bazaar photographing shoes and accessories for fashion spreads. He was distressed by American business practices and the ‘time is money’ attitude of the magazine’s editors, attitudes that mirrored those of his family in Switzerland. The following year Harper’s Bazaar closed their in-house studio. Frank, unemployed, began to travel widely (presumably on his family’s money). Between 1948 and 1953 he toured South America and Europe. Between trips, he appears to have balanced his time between Zurich and New York City. Some of the time he traveled with his family (he married in 1950; his first child, Pablo, was born the following year and his daughter, Andrea, in 1953), some of the time he traveled alone.

Of course, he shot photographs everywhere he went. His work during this period concentrated mainly on the social, cultural and political facets of the lands he visited—topics he would focus on for The Americans. Frank began to gain something of a reputation. His work appeared in photography magazines, he had small exhibitions in Zurich and New York (including in a show at the Museum of Modern Art), he published a few small editions of photography books. In the photography community, Frank was often presented as an example of a student of the New Photography school whose work had shifted toward a more expressive and less formal style. In the early 1950s one critic wrote that Frank united “the unarranged, the discreet, and the completely un-theatrical” with “an unmistakable human touch.”

The deliberate quality of the exposure and composition in these early photographs demonstrate Frank’s formal training, but his willingness and ability to incorporate randomness reveals his versatility. These images suggest some of the stylistic techniques that would come to mark his most famous work—the wide angle lens, the hurried but conscious attention to composition, the use of fast film to shoot under low light conditions, the willingness to get close to the subject while remaining emotionally clinical and distant, and the awareness of class and race as subject matter.

That last factor—the attentiveness to class and race—is critically important. Even then Frank was consciously using class and race as elements of composition. Think about that for a moment. Those social circumstances weren’t just subject matter, but were intentional aspects of composition as important as—and maybe more important than—traditional elements like lighting or the geometry of form and line. Implicit in that is the evidence that Frank knew he was making art, even if the art appeared in the guise of photojournalism. In fact, as early as 1951 Frank told an interviewer,

“When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.”

On his initial visit to the U.S. in 1947 Frank was unabashedly enthusiastic and optimistic about America. When he returned to New York in 1953, he’d lost much of that zeal and hopefulness. In fact, he wrote to his parents that “This is the last time I go back to New York.” Despite his growing pessimism, Frank made two critically important decisions. First, he applied for U.S. citizenship. Second, he applied to the Guggenheim Foundation for a grant to travel and photograph the country he intended to adopt. The result, of course, was The Americans, which has forever inextricably linked Robert Frank with American culture (which we discussed in the previous salon).

Frank returned to New York City after completing his two-year trek. In the summer of 1958, while awaiting publication of the book, he began a series of photographs shot from the windows of city buses. There is something endearing about these images, perhaps because they are so determinedly passive. Having spent two years actively searching for America, Frank was allowing mass transit and the happenstance of pedestrian life to determine his subject matter.

The bus series was all about movement and the transience of time. Combine that with his insistence on the sequential ordering of images in The Americans and it’s not surprising, that Frank would become interested in cinema. In 1959—shortly after publication of the English edition of The Americans—Frank set aside his Leica cameras. For the next fifteen years, Frank’s dominant mode of expression was cinema.

He made a number of films, two of which have become cult classics: Pull My Daisy, written and narrated by Kerouac and Beat poet Alan Ginsburg, and Cocksucker Blues, a documentary of the 1972 American tour by the Rolling Stones. Cocksucker Blues has been called one of the best films about the “loneliness and despair of life on the road.” The film was so honest in its portrayal of drug use and sexual behavior that the Rolling Stones, fearing they’d never be allowed to tour the U.S. again, sued Frank to prevent its release. The court ruling is singularly odd; the judge ordered that the film could only be show five times per year and then only in the presence of Frank.

In 1971 Frank bought an old fisherman’s shack in Mabou, Nova Scotia on Cape Breton Island. He began to divide his time between there and his loft in New York City. He took up his Leicas and bought a cheap Polaroid, and returned to still photography. The photographs he began to shoot in Mabou were, at first, relatively simple in composition, but they were significantly more introspective and personal than anything he’d done before. His earlier work was all about the external world; his new work was deeply internal. It was less about others and more about himself. It’s as if Frank began for the first time to use photography as a mode of personal expression. The photographs retain the air of melancholy that marked his more famous work, but the melancholy grew out of the style of the work—out of the photographer, it could be said—rather than from the subject matter.

Some of that grew out of his personal life. Frank’s son Pablo was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the early 1970s, and eventually he required hospitalization. In 1974 Frank’s daughter Andrea died in an airplane crash in Guatemala. These personal tragedies clearly began to shape Frank’s work. It became more raw and almost painfully personal.

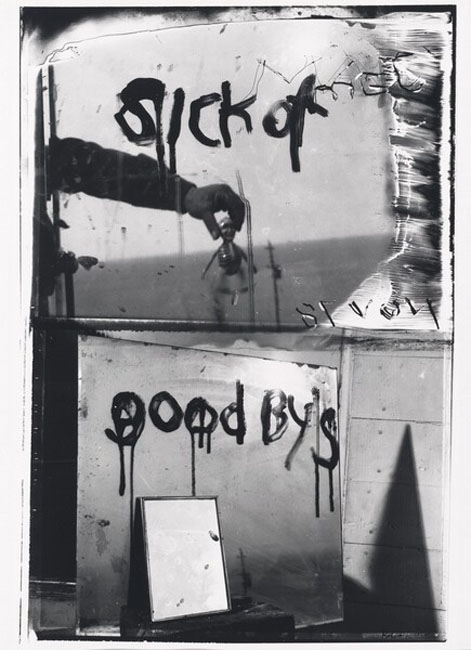

Frank had long felt discontented by the lack of narrative power of a single photograph. In The Americans and the bus series, he’d tried to augment the power of a solitary photo by arranging individual images into a sort of narrative sequence. When that didn’t prove entirely satisfying, he moved into cinema. After the death of his daughter, Frank began to impose a narrative directly onto the image by adding text, sometimes scratching the words onto the print—or even onto the negative itself. He began to create complex multi-image arrangements, situating two or three or six or even nine images into a single frame.

In effect, Frank began to break apart the concept of a traditional photograph. While it may be a stretch to compare the way he shattered his photographs to the shattering of his son’s personality and the shattering of his daughter’s aircraft, it is nonetheless clear that Frank couldn’t express the rawness of his emotions through traditional modes of composition. In a nine-panel image from 1975, for example, four of the panels are blank, four are deliberately damaged images that show what appears to be the hut in Mabou, and one—the only unspoiled panel—shows his smiling daughter; in one of the panels Frank has scrawled the following:

for my daughter Andrea who died in an Airplane crash in TICAL in Guatemala on Dec 23, Last year. She was 21 years and she lived in this house and I think of Andrea every DAY.

Twenty years after the death of his daughter, Frank’s son Pablo died in a psychiatric hospital in Pennsylvania.

On the first page of his 1989 book of photographs, The Lines of My Hand Frank writes:

I have come home and I’m looking through the window. Outside it’s snowing, no waves at all. The beach is white, the fence posts are grey. I am looking back into a world now gone forever. Thinking of a time that will never return. A book of photographs is looking at me. Twenty-five years of looking for the right road. Post cards from everywhere. If there are any answers I have lost them.

From the 1950s on, Robert Frank’s work seems to have always had an element of searching, of looking for something—something that’s maybe just beyond the horizon. Maybe. Whatever it is he’s been seeking, he doesn’t seem to have found it.

The things he’s found over the course of his long career haven’t always been the things he wanted. Fame, for example. Frank has been known to quote Jack Kerouac’s line that being famous is like old newspapers blowing down Bleeker Street. But in truth, Robert Frank isn’t—and never was—truly famous, except among students of photography. In a very real sense, what Frank achieved is both more important and more burdensome than mere fame; he became influential. He re-shaped the course of modern photography. Echoes of The Americans appear everywhere, even in the photography of people who don’t know Robert Frank, people who’ve never heard of the book. The resonance of those half-century-old images continues to be felt in everything from fine art photography to advertising. Those newspapers Kerouac referred to—the ones blowing down Bleeker Street—would probably have pale imitations of Frank’s work somewhere in their pages. Even though Frank himself moved on, he must encounter facsimiles of his early work everywhere he goes—except, perhaps, in his fisherman’s hut in Mabou, on Cape Breton Island, at the very edge of the world.

Whatever Robert Frank has found over the years, I suspect he’d give them all up in exchange for the things he’s lost.