Here are some simple facts. Diane Nemerov was born in 1923 to a wealthy family in New York City. Her father was the vice president and fashion director of Russeks—one of New York’s most popular furrier shops which later became a department store specializing in women’s clothing. Her grandfather was Russek himself. As a child her family traveled frequently to Europe and summered in Maine and Cape Cod. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, they lived in a fourteen room apartment in the San Remo, one of New York’s finest apartment buildings. They had a staff that included two maids, a chauffeur, a cook, and a governess for each of the two children (Diane and her brother). She attended private progressive schools and when she decided to study art, was tutored by well-known New York painters.

A few more simple facts. At fourteen she fell in love with a young man only a few years older than herself—Allan Arbus, who was employed in the advertising department of Russeks. In 1941, when she turned eighteen, they married against her family’s wishes. He wanted to be an actor (and would eventually succeed, being best known for the recurring role of Dr. Sidney Freedman on the television series MASH). She only wanted to be Mrs. Allan Arbus. He bought her a camera (a twin reflex Graflex), which he used while on holiday to photograph her making fashion poses. On the basis of those photographs, her father hired them to shoot advertisements for the store.

And still more facts. Allan joined the Army at the beginning of World War II and was assigned to a photographic unit of the Signal Corps. He was eventually posted overseas to the Indian subcontinent. After he left, Arbus discovered she was pregnant. Using a 5×7 view camera given to her by her father, she shot a series of photographs depicting her growing pregnancy—her first semi-serious entry into photography. At the end of the war, Arbus and her husband began a successful fashion and commercial photography business.

That’s the end of the simple facts. The hard fact is there was very little about the life and work of Diane Arbus that was simple. She was born to wealth and privilege. She was clever and by most accounts, could be entirely charming when she chose. She married the man of her dreams, and they were engaged in work that allowed them to be creative and meet interesting people. Over the years they had two beautiful, intelligent children. They had, by almost any measure, everything you’d want in a good life.

So how the hell did she wind up dead at age 48? Alone, fully dressed in a bathtub, with her wrists slit and barbituates in her system…how?

The physical distance from 115 West 73rd Street, where Arbus was born, and 463 West St, where she died of exsanguination and barbituate poisoning, is only a couple of miles. The emotional distance, however, is vast.

She was shy as a girl, and timid, uncomfortable with praise, believing she didn’t truly deserve it. Years later her brother told an interviewer, “We were protected and privileged as children, but we were watched over incessantly. It made us fearful.” For all that, she could be willful, stubborn and rebellious. She also suffered from periodic quiet bouts of melancholy.

“One of the things I felt I suffered from as a kid,” Arbus said, “was I never felt adversity. I was confirmed in a sense of unreality which I could only feel as unreality…. I could learn things but they never seemed to be my own experience.” That air of unreality which began as a child, continued through most of the early years of her marriage—and perhaps through her entire life.

The photographic collaboration of Allan and Diane Arbus was uncommonly close and strangely co-dependent. Arbus would create the concepts for the fashion shoots and her husband, whose photographic training in the military made him a meticulous craftsman, would handle the technical aspects (lighting and processing, for example). They both worked behind the camera, often huddling together beneath the dark cloth, whispering to each other and studying the ground glass. After a few shots, they’d adjourn to a corner and confer about the process. An editor at Condé Nast described them as “like little kids acting out a storybook marriage. The whole thing didn’t seem quite for real.”

Arbus would accept praise and encouragement from her husband that she couldn’t accept from others. It’s quite clear he recognized she was more creative than he was, and by all accounts he was genuinely pleased about that. During a year (1951-52) they spent abroad in France, Spain and Italy, they each practiced their own photography. They’d both studied the photography of Cartier-Bresson and Allan made a serious, conscious attempt to shoot more freely and intuitively—which, of course, doomed those attempts to failure. Arbus, on the other hand, shot without much consideration for technique; she was more interested in what was being photographed than with photographing it. Sometimes she carried her camera around without any film in it, merrily snapping away at things that caught her imagination.

After their return from Europe, Arbus became increasingly dissatisfied with the commercial and fashion photography that supported her and her husband. Although the photos were technically solid and financially rewarding, they were uninspired. An editor at Condé Nast described their work as “pictures that sold fashion, but you didn’t get excited by them.” Arbus became intrigued by the work of more documentary photographers—especially people like Robert Frank, who in the mid-1950s had recently completed his two-year Guggenheim-funded sojourn around the United States and was starting to show the ragged, savage photographs to his friends.

In 1956, things changed—and changed radically.

Arbus decided to withdraw from commercial photography (her husband continued the business). She enrolled in workshops with Lisette Model and Alexey Brodovitch, neither of whom cared that she was part of a moderately successful fashion photography team. They treated her like any other student. “If you see something you’ve seen before,” Brodovitch often said, “don’t click the shutter.” She was fascinated by Model’s large images (16×20 was considered large at the time) of beggars and drunks and people whose lives were outside the norm. “When I point the camera at something,” Model told her students, “I am asking a question, and the photograph is sometimes an answer.” Arbus also began to study the work of earlier photographers to see what they photographed, how they photographed it, and why they photographed it. She was apparently especially taken by the work of Weegee, the tabloid photographer.

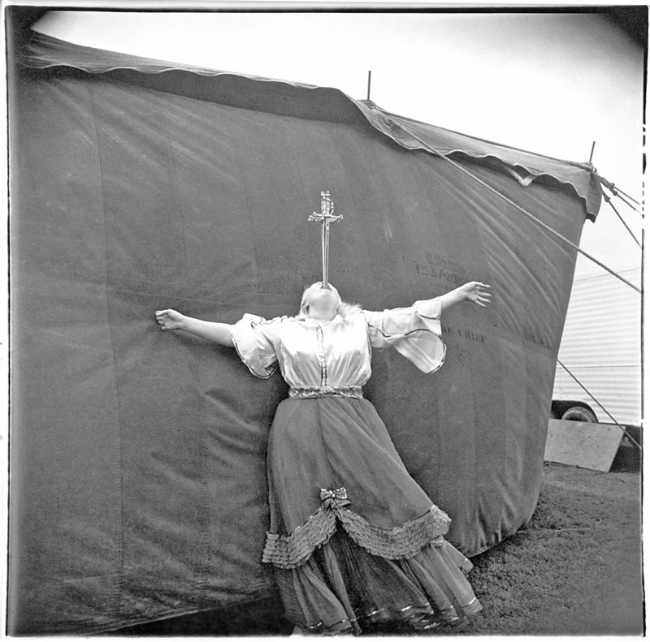

She put aside the view camera and her medium format equipment (in the early 1960s she reverted back to medium format) and bought a 35mm Leica like that of Robert Frank. Arbus became smitten with the grain of film, which of course was anathema to commercial photography. A friend took her to see Todd Browning’s 1932 movie Freaks, which featured “midgets, pinheads and dwarfs” and she returned to watch it over and over. She began to spend time at Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus on 42nd Street (home to Sealo the Seal Boy, and Alberto Alberta—half man and half woman, and Congo the Jungle Creep, and a fire-eater and a man with three legs), often taking along friends and other photographers (including Joel Meyerowitz).

In other words, Arbus began to step away from the safety and security of her wealthy Manhattan circle and delve into the world of the strange and the sordid, the outré and perverse, the willfully weird, the crazy, the disabled, the very very different. In an amazingly short period of time—a matter of a few months—she completely shifted her approach and began to take the sorts of photographs, and to photograph the sorts of people, that would make her famous.

She was 35 years old, the mother of two, and on the road to subverting the practice of photography.

It wasn’t easy for her. She was a small woman—five foot six, around a hundred pounds. She was still painfully shy, and reluctant—afraid, in fact—to introduce herself to the people she wanted to photograph. But she did it. Her daughter later wrote: “She liked being afraid because there was in it the possibility of something terrific.” A certain level of fear and uneasiness also helped keep away the depression; it kept her engaged in reality. There was also a sense of liberation that came from overcoming her fear and shyness, a liberation that was only possible because she was carrying a camera.

“Photography was a license to go wherever I wanted and to do what I wanted to do.”

And then, of course, there were the photographs, which were often shocking. As a child, like most children, she’d been taught not to look at people who fell outside the mainstream—people with disabilities or medical conditions, people who were mentally unbalanced, people who were disfigured, people who were visibly and often deliberately different. The camera gave Arbus permission to look. Not just look; she could stare. And she did. “Diane was fascinated by weirdos,” according to James Randi (the Amazing Randi, a well-known stage magician and escape artists who introduced her to some of the stranger people he knew). “Not just by their weirdness, but by their commitment to weirdness.”

To Arbus, these people (whom she called ‘freaks’) seemed to represent a sort of victory over fear—both hers and theirs. “Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience,” she told a New Yorker staff writer. “Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.”

It’s important to understand the social context in which Arbus began making these images, to consider what the U.S. was like in the mid-to-late 1950s. It was only a decade after the horrors of the Second World War (a war whose photographs made it somewhat more acceptable to shock the public). This was the era of the Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, the true beginning of American corporate culture which emphasized the value the Normal and the comfort to be found in being Ordinary. And here was this nice Jewish girl actively seeking out the truly abnormal and the anomalous and photographing them because they were abnormal and anomalous.

In 1959, Arbus separated from her husband, though they remained close friends and he continued to support her financially (even after their divorce a few years later). Although many photographers and art directors loved her work, she had a difficult time selling her photographs to magazines. The images might have been intriguing and brilliant, but they weren’t necessarily something readers (or, more importantly, advertisers) wanted to see. Then in 1960-61, Esquire planned an issue devoted to New York City. The editors loved her work so much they considered having Arbus provide all the photographs for the issue. She worked for months on the gig, photographing everything from the New York City morgue to Rolls Royces parked outside the Plaza Hotel, from Boy Scout meetings to a slaughterhouse. In the end, although everybody was amazed at the scope of her work and her ability to go anywhere and photograph anything at any time of day or night, the magazine only published six of the photographs.

Still, everybody recognized Arbus was the real thing. They might not have liked her work, they may have questioned her talent, but nobody could claim she wasn’t committed to the work. She was driven—by passion, by curiosity, by fear, by the thrill of facing down her fear, by loneliness, by a need to fill an emotional emptiness, by the necessity to stave of depression, by creative energy. She was given a couple of Guggenheim grants, she continued to receive magazine assignments (though her photos weren’t always printed), she was asked to teach at Parsons School of Design.

Eventually she received some tangible recognition; her work was included in The New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The response to her photos at that 1967 show solidified her reputation as a photographer. Her work—a series of 30 photographs of nudists, midgets, transvestites and carnies—was set off in a room separate from that of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, the other featured photographers. It was set apart because it was so controversial. According to Yuben Yee, the photography librarian at MoMA, people were known to spit on Arbus’s photos. It happened often enough he was forced to arrive early during the exhibition to clean them off.

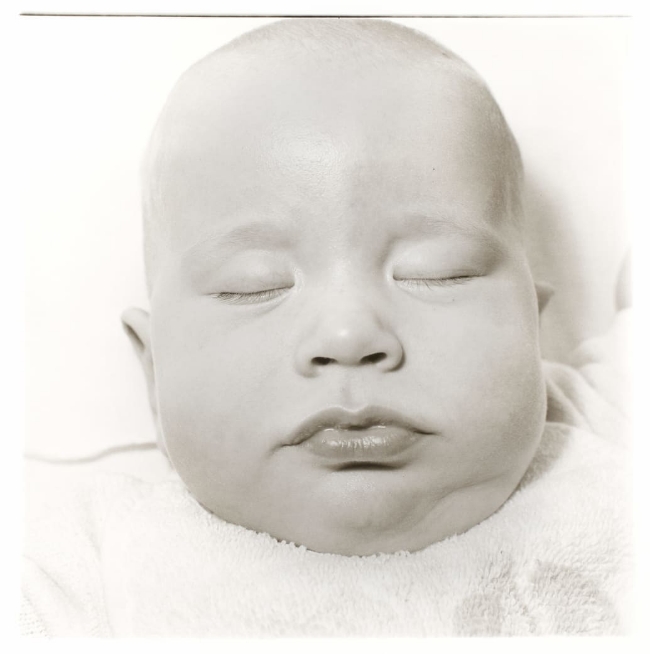

Some of her subjects were pleased by the attention Arbus gave them, and enjoyed the interest her photographs brought to them. Others weren’t enthused. Arbus shot a portrait of Gloria Vanderbilt’s son for Harper’s Bazaar that she found so horrifying (she described it as looking like a Roman death mask) she refused to allow the magazine to publish it (the baby, by the way, grew up to be Anderson Cooper, the CNN journalist). The parents of the identical twins depicted in one of Arbus’s most famous portraits attempted to stop its further publication, claiming the photo was a distortion and would cause the girls serious harm. Arbus’s treatment of feminist Germaine Greer was so outlandish that three decades after being photographed by her, Greer was still angry and offended by it.

By the mid-to-late 1960s Arbus had begun to drift away from photographing what Lisette Model called ‘eccentrics’ and was turning her camera on ‘normal’ people. Being Arbus, of course, she photographed them in ways that made them appear abnormal.

And there it is. There is the reason critics and art theorists love and despise Diane Arbus. They admire her and loathe her in part for who and what she photographed, and in part for how she photographed it. Some praise her courage for going where other people were leery of going and her candor for photographing things others would turn away from—things they may secretly want to look at. Others, however, were (and still are) offended by the way Arbus actively sought out subjects who were ‘different’ in some overt way.

Although she obviously recognized the beauty of everyday moments—as shown in some of her earliest work—she was drawn by things others would find ugly or unseemly. Her interest, it seems, was purely to see what there was to see, to face it without flinching, and to document it. She doesn’t seem to have been drawn to the people she photographed because of compassion (although she clearly came to be attached to many of them). She was drawn by curiosity. Photographer Saul Leiter, who was her neighbor for a time, recalls Arbus once asking if he knew any battered women she could photograph—not because she wanted to make some sort of statement about violence against women, but because she thought they might have interesting faces.

Arbus is also accused of “enfreakment,” of turning otherwise ‘normal’ people into ‘freaks.’ This was clearly a deliberate choice on her part. She did it primarily by exaggerating some aspect of the subject. “You see someone on the street,” she said, “and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw.” She often photographed people at an uncomfortably close range. She also engaged in “enfreakment” by finding the most bizarre members of an otherwise ‘normal’ crowd, or by selecting the most unusual frame from the contact sheet. For example, ten of the eleven frames Arbus shot of the boy pictured below show him smiling and laughing like any other child; the grimace he displays in the frame she printed came from the boy expressing a child’s impatience for her to ‘take the picture, already.’

By the summer of 1971 Arbus was getting older and troubled by it (one of the reasons she was able to get people to let her photograph them was by looking young and being cute); her ex-husband had remarried and moved to California to pursue an acting career; her children were growing up and increasingly independent; she was engaging in lots of casual sex with strangers (including some of the subjects of her photos); and despite her growing reputation as an artist she was still finding it hard to sell her work. Did those things lead her to kill herself? Who knows? She left no note, made no farewell telephone calls, paid no last visits. She simply took an overdose of barbituates, climbed into her bathtub, and sliced open both her wrists.

There was, I think, something almost alien about Diane Arbus. She often spoke about a sense of unreality to her life, and it seems to me she attempted to inject reality into it by compulsively seeking out new and radically strange experiences. Susan Sontag suggests Arbus’s “interest in freaks expresses a desire to violate her own innocence, to undermine her sense of being privileged, to vent her frustration at being safe.” Maybe. But I’m more inclined to believe she tried to reassure herself of her own reality by weighing it against the lives of people who seemed to her to be more alien than she was.

“{T]here are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them.”

I avoided writing this Sunday Salon for a couple of years. There are some photographers whose work immediately makes sense to me. There are some whose work only begins to make sense after I’ve given it close attention, or after I’ve looked at enough images that the point of the work eventually sinks into my brain. And there are some photographers whose work seems to hover just outside my grasp. For me, that includes Diane Arbus.

I find her early work accessible and touching, and her later work (especially the series of photographs of “middle-aged retardates” living in a home in Vineland, New Jersey) is often hauntingly beautiful, although they sometimes strike me as cruel. But the photographs for which she is most famous generally leave me cold. There is a clinical detachment I find off-putting. Perhaps that detachment was necessary for her to get that close—physically and emotionally—to the subject, but I don’t always feel anything for the people. I’m mostly moved—and not always in a positive way—by the fact that this woman chose to take that photograph. So many of those photos reveal more of the photographer than they do of the subject.

Thirty-eight years after her death, those photographs retain some strange power to draw and hold our attention. I don’t necessarily like it—or what it says about her, or what it says about us as a society—but I appreciate the integrity of it.

Diane Arbus lived one hell of a life, in every sense of the term.