Great cities radiate life—and life, of course, is always changing, always in flux, always moving forward. Yet great cities are also grounded very firmly in history, in the lives of people long gone. Great cities append the promises of the future to the guarantees of the past.

That’s one of the reasons great cities attract great photographers. The collective energy generated by that many people of that many different ethnicities and races and religions going about that many different tasks with that many different motives is a magnet for photographers. Down at the bone, great cities spark passion in the people who live in them. Certainly, those people who seek to document a city are among the most passionate of photographers.

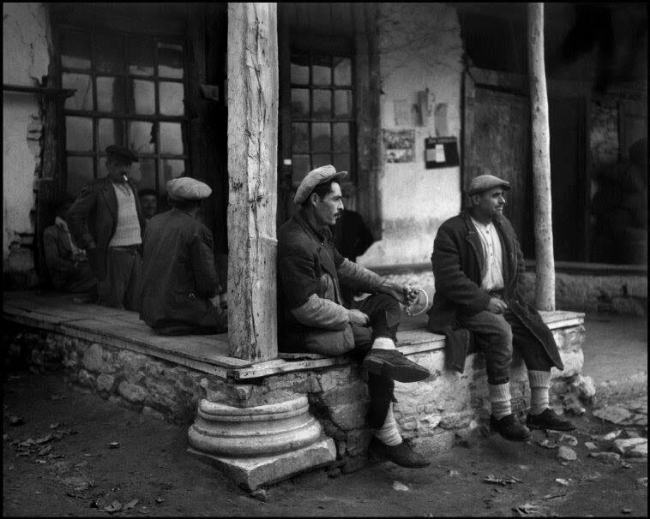

For half a century, Istanbul has had such a photographer in Ara Güler. In articles about him, he’s often referred to as the ‘Eye of Istanbul’. It’s an absurdly romantic soubriquet, but it somehow seems completely appropriate when applied to Güler. The Eye of Istanbul—it sounds like the title of a spy novel, and that’s also appropriate. The very best street photographers are rather like spies. They have to know how to watch others without being watched themselves, and they must be intensely aware of what’s going on around them. They need to be as familiar with the quietest side streets as they are with the busiest thoroughfares, and to be at ease in both. They have to understand the individual rhythms of the different neighborhoods and the people who live there.

Güler is a native of Istanbul, and he has a native’s love and disdain for the city. He was born in 1928 in Beyoğlu, an historic neighborhood which lies across the Golden Horn from Sultanahmet, the old city. He continues to live there. As a child, he was fascinated by the cinema and his boyhood dream was to become a movie director. At some point in his late teens, however, his father gave him a 35mm camera and still photography became his passion.

In 1948, at the age of 20, Güler was hired as a photographer by one of Istanbul’s smaller newspapers. He took every assignment offered to him, no matter how dull or inconvenient or dangerous. When the newspaper complained that he shot five rolls of film for every roll the other photographers shot, Güler paid for the extra film himself. He just wanted to shoot photographs.

His skill quickly became evident, and he was soon offered a position with a better newspaper, and then with a national magazine, and eventually he began to work for international newspapers and magazines—Paris Match, Stern, Time-Life, Newsweek. By the early 1960s he was invited to joined Magnum, the prestigious photo agency (he has since left the agency). Güler spent the next year traveling the world, photographing presidents and prime ministers and movie stars and scientists, photographing famines and wars. His photographs have been displayed in galleries in the U.S. and Europe, his work has been published in books. Ara Güler established himself as Turkey’s most successful and well-known photographer.

And through it all, he consistently returned to Istanbul, to his home, to his old neighborhood. He continued to photograph his city and the people who lived and worked there. All the photographs in this salon were shot in or around Istanbul.

Istanbul is old. In the U.S. we think of our East Coast cities as old. They’re not. New York City, for example, was a thinly-populated forest when London was a major city. In the U.S., we think of London as old. It’s not. When London was little more than a collection of huts gathered around a wide spot on the river, Istanbul had already been a major metropolitan center for hundreds of years. Istanbul is old.

It was originally called Byzantium, named for King Byzas of the city-state Megara, nearly seven centuries before the beginning of the Common Era. Later it became Constantinople, after the Emperor Constantine, and eventually took the name Istanbul (from a Greek term meaning ‘in the city’). It’s served as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, of the Latin Empire, and of the Ottoman Empire. The city isn’t quite in the Western World and it’s not quite in the East; it sort of straddles the two. That, of course, is one of the reasons Istanbul has been so important historically. It’s one of the reasons the city is unique in the world. It’s one of the reasons Güler loves it so, and why he has tirelessly documented it.

“I understand the smell of Istanbul,” he told an interviewer. “Istanbul became my subject because I was born here, grew up here and I know this place intimately.” Like almost everybody who loves a particular city, Güler is concerned that those aspects which make the city unique are rapidly being lost. “The real population of Istanbul is one million,” he’s said. “Today, thirteen million people live here. We have been overrun by villagers from Anatolia who don’t understand the poetry or the romance of Istanbul.”

Güler (who, by the way, is of Armenian descent) is perfectly aware that it’s the people of Istanbul who make the city what it is, just as much as—or more than—the physical infrastructure. His photographs of the working people of Istanbul often show Aya Sofia in the distant background. That’s no accident. Aya Sofia, the great cathedral built in early 6th century by the Emperor Justinian (which became a mosque 900 years later, and is now a museum), isn’t just a beautiful background; it’s the most recognizable symbol of Istanbul. Güler is deliberately connecting the symbol and the people who pass in front of it. That unspoken connection, in my opinion, make these Güler’s most powerful photographs.

There is a striking incongruity in those photographs. The people we see walking across the bridges, toiling in the boats, serving and drinking tea—these aren’t the people for whom Aya Sofia was built nearly fifteen hundred years ago. It was built by the powerful for the powerful and influential. The people in Güler’s photos are the sorts of people who did the building, the people who paid the taxes to pay for the construction, the people who kept the structure clean and in good repair. The distance—political, economic, social—between the people in the photographs and the cathedral-mosque-museum in the background is immense (as well as unacknowledged). Yet Aya Sofia remains the most evident symbol of their city, and very likely the people in Güler’s photos are proud of it.

Aya Sofia is also a symbol of Istanbul’s past glories. As noted earlier, Güler believes what makes his city unique is gradually being lost. That sense that something important is disappearing forever is also what moved Atget to photograph Paris, it moved Sudek to photograph Prague, it moved Curtis to photograph the native peoples of the American West and moves Christenberry to photograph the American South. The permanence of Aya Sofia in the background suggests the transience of the people in the foreground. These people will die and be forgotten, new people will arrive (and, in their own time, die and be forgotten), but Istanbul and Aya Sofia will remain.

There is a certain irony in the fact that Güler’s work for Western magazines and newspapers have helped in some small way to hasten the very thing that Güler fears. By bringing modern Western popular culture to the attention of the common people of Istanbul, those media are gradually re-shaping the culture of Istanbul in both positive and negative ways.

Güler quite clearly identifies with the people he photographs. He considers them to be his people, the people he grew up with, and his affection for them is evident. But it’s the nature of street photography to objectify the people inside the frame, to treat them as ‘the other.’ Once the photographer trains the lens on them—whoever they happen to be—they necessarily become ‘the other.’ No matter how much he respects them, no matter how much affection he feels for them, no matter how sympathetically he photographs them, Güler, as a successful photojournalist, is not one of them. On some level, he acknowledges that.

Güler generally refers to himself as a simple press photographer. On occasion, he’ll admit to being a “visual historian.” He doesn’t consider himself to be an artist, nor does he believe photography is an art. Photography, he says, “is more important than art.” Art, he argues, isn’t real. What takes place in front of the camera of a press photographer is. “Hamlet dies on the stage every night. Why? Because theatre is fictitious. Photography is the truth. If Hamlet dies I can only photograph him at the moment of death.”

Güler has also said “My job is to travel and record what I see.” That’s a wee bit disingenuous. He records what he wants others to see. What he wants us to see isn’t Istanbul as it is; he wants us to see the city and the culture he grew up with, the city he fell in love with. It was a great city, worthy of his passion. And it still is.

It’s a safe bet that right now in some neighborhood in Istanbul, there’s a boy with a cheap digital camera or cell phone falling in love with the city just as it is.