DISTURBING IMAGE == DISTURBING IMAGE — DISTURBING IMAGE

Cindy Sherman’s photography comprises an aesthetic of questions. What’s going on here? What is she saying—or trying to say? What does all this mean? And then, of course, there’s the question that underlies all the other questions: just who the hell IS Cindy Sherman?

She is, surprisingly, a 56 year old woman (or soon will be—she was born in January of 1954) who is moderately inarticulate, relatively modest, and apparently more than a wee bit anxious about the potential for violence in the world. She was the youngest of five children born to a reading teacher and her engineer husband. She grew up in Huntington, Long Island. Her parents weren’t terribly interested in the arts and Sherman apparently surprised them by announcing she was going to study art in college.

She attended the State University College at Buffalo, where her focus was on painting—kore specifically, realist painting. She took an introductory photography course as a freshman, but failed it. Since it was a required course for her major, she was forced to repeat it—but this time with a different teacher, one who introduced her to conceptual photography. Sherman soon became frustrated with painting as a medium. “I was meticulously copying other art,” she’s said, “then I realized I could just use a camera and put my time into an idea instead.”

After graduating from college in 1976, Sherman moved to New York City and rented a small loft apartment on Fulton Street in Brooklyn. In those days, it wasn’t an entirely safe neighborhood. She was reluctant to leave her apartment at night

“When I first moved to New York I was shocked at how I was treated when I walked down the street. So I changed my persona for the street. In order to feel comfortable in this city you have to have a street persona and another persona when you get inside.”

Driven in part by her anxiety over her safety, Sherman began to shoot photographs of herself at home.

This is where things begin to get interesting. Although Sherman was the model in the photographs, she was not their subject. These are not self-portraits. A portrait—whether it’s of somebody else or a self-portrait—is by definition an attempt to portray a specific individual, usually an actual person. Sherman, in contrast, was photographing generic types of characters commonly found in movies and television.

In order to understand the early images Sherman created—and to understand her work in general—it’s necessary to remember she belongs to that first generation of children raised on broadcast television. Where earlier generations had been raised on books and learned to think in terms of text and words, Sherman was raised on imagery. Those childhood visual tropes were filtered through the postmodern theories and ideas that were prominent at the time she was a university student—feminism, notions about mass culture, the acceptance of subjectivity (as opposed to objectivity) as a valid approach to understanding the world, the recognition of popular entertainment as a subject worthy of exploration and analysis.

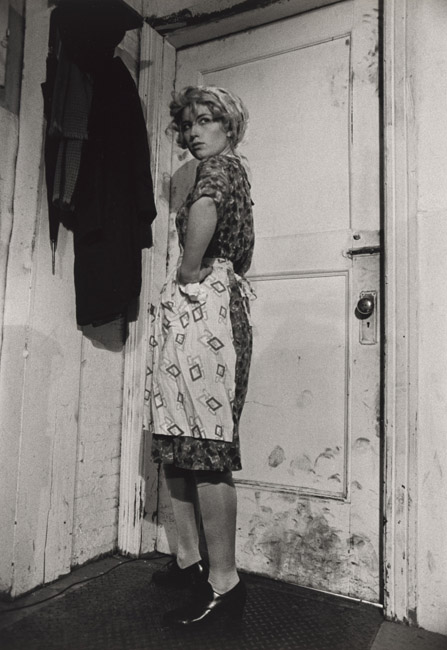

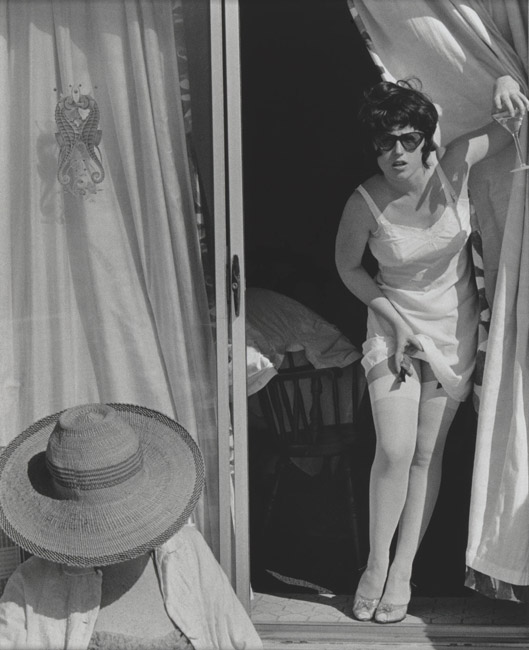

Those ideas eventually coalesced into a series of photographs Sherman called Untitled Film Stills. That name—Untitled—underscores the deliberately generic nature of the images. No titles, no attempt to create or impose a narrative, not even the suggestion of individuality; there’s nothing but an undifferentiated moment lifted out of and isolated from all the other moments of a black and white movie of the 1950s or early 60s. The photographs are removed from the concept of sequence and deprived of context; they’re purposely moment-oriented. They tell us nothing about what happened before that moment or what may come after; the photographs exist entirely in a vague and ambiguous now. Yet they offer some very slight, evocative suggestion that the characters in this series have a life outside that moment and that frame.

Untitled Film Stills brought Sherman a great deal of critical attention, some positive and some negative. The clearly contrived scenes made some critics bristle; others thought they were brilliant. Their success led her to extend the series beyond the concept of film stills. She also began shooting in color.

Although she doesn’t consider herself very political, Sherman acknowledges the existence of a feminist sensibility in her work. With few exceptions, she doesn’t try to make an ideological statement through her work. Still, the personal issues she addresses are infused with her understanding of the world. There’s an unintentional but logical progression in the various series of images she creates. The role of women in film and television—so often sexualized victims or saintly homemakers—led to a series she called Centerfolds.

Not surprisingly, Sherman’s centerfold photographs weren’t what one would expect from a centerfold. She wanted to create the perception of “a man opening up a magazine…with an expectation of something lascivious and then feel[ing] like the violator they would expect to be—looking at this woman who is perhaps a victim…. Obviously, I’m trying to make someone feel bad for having certain expectations.”

The progression of her work continued to follow a subtle but internally consistent path. Her study of centerfolds led to a study of fashion (sexualized and objectified women), which led to an examination of fairy tales (gruesome morality tales that required her to use prosthetics to change her appearance), which led (after an interlude into pseudo-historical portraiture) to what Sherman called the Sex Pictures.

The progression of her work reflects more than a progression of ideas and beliefs. It also demonstrates a progression in approach. Sherman’s initial photographs used relatively few props—just clothing. As her photographs became more sophisticated, so did her props. During her Centerfold series, she began to incorporate prosthetic body part culled from the pages of medical educational catalogs. Each new series tended to utilize more prosthetics and less of Sherman herself. By the time she began the Sex Pictures series, the photographs were exclusively of prosthetic body parts.

With her Sex Pictures Sherman posed medical prostheses in sexualized positions, recreating—and strangely modifying—pornography. The images are, for most people, difficult to look at. Even Sherman’s friends found the series distinctly uncomfortable.

“A few people that I would run into on the street would say, ‘Oh, you know I liked the show but I sure couldn’t bring my child in there.’ I could sort of understand, I guess. But on the other hand they are just dolls.”

They are just dolls—or, rather, bits culled from several different medical anatomical mannequins. But they’re exceedingly discomfiting dismembered dolls, posed in graphically and weirdly contorted sexual positions. They’re dolls that can embarrass us. The Sex Pictures series combines the gruesome qualities of fairy tales with the victim-oriented centerfold images and adds a grotesque and blatantly sexual quality. The combination is disturbing to say the least. They’re even a tad disturbing to Sherman herself:

“I have this juvenile fascination with things that are repulsive. It intrigues me why certain things are repulsive. To think about why something repulses me makes me that much more interested in it.”

It’s not surprising that many people find the Sex Pictures images offensive. In a way, Sherman deliberately made them offensive. The series was created, in part, as a response to the controversy surrounding the attempts of conservative legislators to punish the National Endowment of the Arts for providing some support to photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano. In classic Cindy Sherman style, though, the photographs act on several levels simultaneously. They are a comment on the intersection of art and taste, they are a comment on pornography and the way porn objectifies the men and women who pose for it, they are a comment on social discomfort with overt sexuality, and they are a comment on the relationship between sex and violence. Yet the emphasis is still on creating a striking image that seems simultaneously familiar and strange.

That’s what Sherman does so exceedingly well. She has the capacity to create an image we’ve never seen before, but at the same time it’s an image that feels like we’ve seen it a thousand times. She forces us to see that familiar image from an entirely new perspective, reinforcing its strangeness. We’ve all had the experience of repeating a common word over and over until it becomes nothing but an odd sound that’s lost all meaning. Sherman does that with photographs. She takes what we think we know, shows us we don’t really know it at all, then leaves us wondering what it is we do know.

As I said at the beginning, Cindy Sherman’s photography comprises an aesthetic of questions.