Berenice Abbott was one of the very few people whose work significantly influenced the course of contemporary photography. That in itself makes her worthy of study. But she did more than that. She influenced the course of photography twice.

She did it first by insuring the legacy of one of the world’s great documentary photographers; she helped his work reach a wider audience and sealed his place in photographic history. She did it the second time by creating a legacy of her own; she built a portfolio of diverse but iconic images that we continue to look at and admire today.

That’s not bad for a young woman born in Springfield, Ohio in 1898.

She was the youngest of four children. When she was eighteen months old, her parents divorced and her father was given custody of the older children. Abbott spent most of her unhappy childhood living with her mother in Cleveland. The world changed for her when she moved to Columbus, Ohio to attend Ohio State University, where she intended to study journalism. But it wasn’t her studies that sparked the change in her life; it was her hair.

“The day I graduated from Lincoln High School…I had the barber cut off the long, thick braid which hung down my back…. My bobbed hair startled the campus. A handful of students from New York at once mistook me for a ‘sophisticate.’ We became friends, and a new life began for me.”

Abbott did not become a journalist, of course. Nor did she finish her degree. Instead, she and her new friends left Ohio in 1918—the year the Great War in Europe ended—and moved to New York City. They rented a small apartment on MacDougal Street in the heart of Greenwich Village. There she lived a classic bohemian existence; at various times during the next three years her roommates included artists and writers like Djuna Barnes, Malcolm Cowley and Kenneth Burke. Abbott spent her time studying sculpture, writing, playing small supporting roles in productions at the Provincetown Theater (located just down the street). She became acquainted with people like Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray.

Following the end of the Great War, many of the bohemians of Greenwich Village gradually drifted to Paris. In 1921, Abbott joined the migration. Two years later, learning her old acquaintance Man Ray had a studio in Paris and was looking for an assistant—somebody who “knew nothing of photography” and would therefore be trainable—she applied for the job. And she got it. Abbott spent the next two and a half years—from 1923 to 1925—learning photography. She learned it so well that in 1926 she was able to open her own portrait studio. Her clientele included writers, painters, sculptors, and wealthy patrons of the arts. Sylvia Beach, the owner of the bookstore Shakespeare & Co., said “To be ‘done’ by Man Ray or Berenice Abbott meant you rated as somebody.” Her portrait of James Joyce is perhaps the most frequently reproduced photo of the writer.

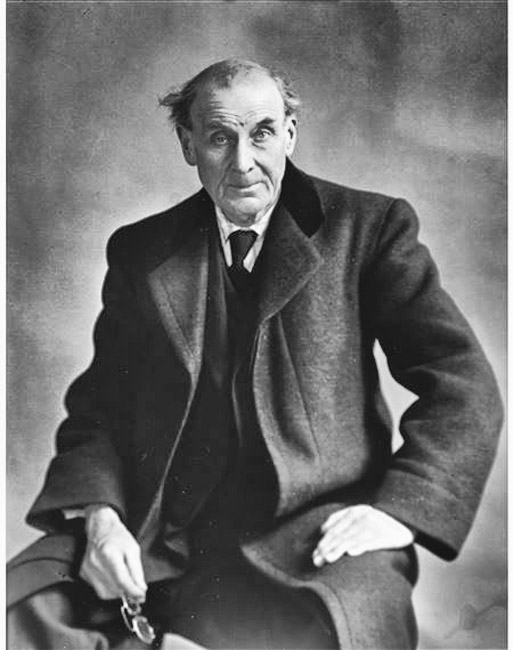

While working as Man Ray’s assistant, Abbott encountered an old man who toted an outdated and heavy camera around the streets of Paris, documenting the city. His name was Eugène Atget, and Abbott quickly became a fervent supporter and advocate of his work. In 1927 she convinced him to to sit for her. A few weeks later when she brought the finished prints to his apartment, she discovered Atget had died.

Atget had labored at his task in poverty and obscurity. Concerned his work might be lost or ignored, Abbott managed to borrow money and raise the funds necessary to purchase 1400 of Atget’s glass plates, as well as nearly 8000 prints. “Atget’s photographs,” Abbott said, “somehow spelled photography for me. Their impact was immediate and tremendous. There was a sudden flash of recognition—the shock of realism unadorned.”

Abbot spent two years sorting through Atget’s prints and plates, and tirelessly promoting his work. In 1929 she returned to New York City hoping to find a publisher for his elegaic photographs of Paris. To her surprise, the city she returned to was not the city she’d left. Her arrival in New York on a quest to promote the passionate vision of another photographer led to a passionate vision of her own.

During the years Abbott spend in Europe, New York City had undergone a radical reconstruction. Zoning laws enacted shortly before she left for Europe had encouraged a second ‘skyscraper boom.’ Rather than restricting the height of buildings, the new laws required a structural design that would allow sunlight to reach the streets below.

“The new things that had cropped up in eight years, the sights of the city, the human gesture here sent me mad with joy, and I decided to come back to America for good.”

She began photographing the city—its architecture and its people—using a hand-held camera. She referred to these initial photos as ‘notes’ for future reference. A year later she acquired an 8×10 view camera, which not only gave her a significantly larger negative, but also imposed a more formal approach to the work. She began to tell friends she hoped “to do in Manhattan what Atget did in Paris.”

And she did. Like Atget, Abbott photographed the inconsequential aspects of the city as well as the more grand and awe-inspiring views. She photographed the storefronts, the barber shops, the bakeries, and the mass transit systems. She photographed the buildings under construction, the old tenements with their queer constellations of clotheslines, she photographed the bridges, the fish markets, and the schmatta men with their carts filled with rags.

It was Abbott’s misfortune to return to New York City, flushed with her success in Paris and confident of her ability to support herself through photography, just in time for the stock market to crash. She attempted to find funding for her Atget-inspired project from a variety of organizations, ranging from the Guggenheim Foundation to the Museum of the City of New York. She was universally rejected. She was forced to seek out commercial work and, in 1933, she began teaching the first photography course offered at the New School for Social Research. This drastically reduced the time she could devote to documenting the city, but she kept at it.

That dedication paid off in 1935, when Abbott’s application for support was accepted by the Federal Arts Project, part of the Works Progress Administration. The arts project of the WPA was created to demonstrate to the American public (and, more importantly, conservative members of Congress) that government funding of public works—schools, parks, highways, and even art—benefited the citizenry in both direct and indirect ways. Abbott’s assignment from the FAP was to photograph the changes in New York City—the very project she was already engaged in.

Inevitably, of course, artistic temperament came into conflict with governmental bureaucracy. Bureaucrats sought a detailed and predetermined plan of approach against which they could measure goals and achievements; Abbott argued that much of photography depended on intangibles such as light and the random behavior of people on the street and so wasn’t always amenable to schedules. Despite these squabbles, the work itself was impressive. In 1937 more than a hundred of her photographs were exhibited at the Museum of the City of New York (which had rejected her application for funding a few years earlier) under the title Changing New York. The show was a success, and Abbott found herself being interviewed and photographed by major newspapers and national magazines like Life (which featured four full page photos of her work).

In 1939 the World’s Fair was held in New York City. The fair was located on the site of a former garbage dump in Flushing, Queens—a site that had been reclaimed as part of the WPA program. The promotional material for the fair included Abbott’s photographs for Changing New York, which was released in book form. The publication of the book sparked another exhibition and another round of interviews and celebratory articles. Critics hailed the work.

Even as her work (which was funded by the federal government and used by the federal government to promote itself at the World’s Fair) was being celebrated, conservatives in Congress continued to fight to cut art projects from the budget. And they succeeded. That same year, reductions in funding resulted in Abbott’s position with the Federal Art Project being cut. Her project came to an end.

After nearly a decade of photographing New York City, Abbott turned her attention in an entirely unexpected direction. She decided to photograph science. She spent the next two decades quietly designing techniques and inventing ways to photograph scientific concepts such as kinetic energy or gravitation. Abbott secured half a dozen patents for the inventions she created during this period, including some like the autopole—a telescopic lighting support to which lights can be attached at any level—that are still in use today.

Abbott received no financial support for her scientific work, and she garnered little or no public recognition for it. She did it simply because she found it fascinating and developed a passion for it. Very few people saw her scientific photography until 1958, when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology asked her to shoot photographs as illustrations for a textbook.

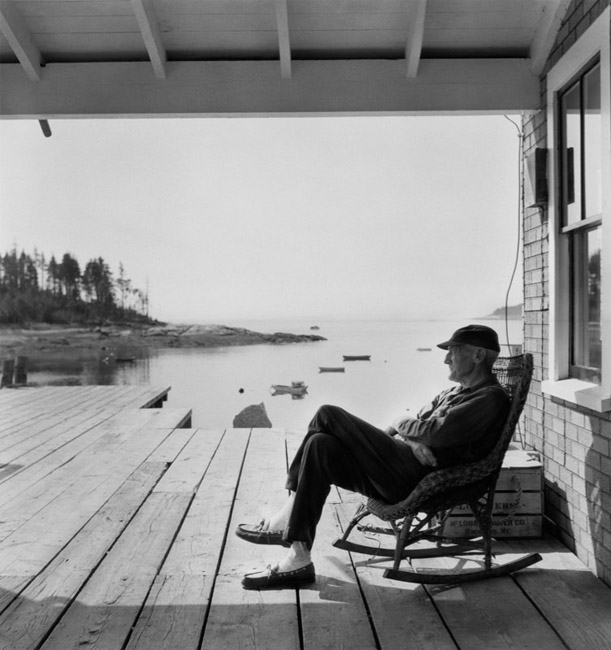

Abbott didn’t completely abandon New York City as a photographic subject, but it seems clear she’d lost her passion for the project. She remained in her Greenwich Village loft until 1965, when her companion of thirty years—the art critic Elizabeth McCausland—died. Not long thereafter Abbott developed a lung condition that was exacerbated by the pollution of city life. She purchased a house in central Maine and moved there permanently in 1968. She remained there until her death in 1991.

Influence in a craft or art like photography is impossible to measure. But there’s no doubt that Berenice Abbott helped mold contemporary photography. She recognized Atget’s peculiar genius and, at great personal expense, insured his work received the attention it deserved. From Atget she learned that passion for a project is more important than recognition, or even remuneration. Her passion for New York City coupled with Atget’s example inspired her to create a series of photographs that have become a model for documentary photography.

Her combination of objectivity and realism imbued by passion resulted in compelling images. During her tenure with the Federal Art Project, when frustrated bureaucrats asked her to distinguish between her ‘documentary’ photos and her ‘art’ photos, she wrote:

“[My] photographs are to be documentary, as well as artistic…. This means that they will have elements of formal organization and style; they will use the devices of abstract art if these devices best fit the given subject; they will aim at realism, but not at the cost of sacrificing all esthetic factors. They will tell facts…[b]ut these facts will be set forth as organic parts of the whole picture, as living and functioning details of the entire complex social scene.”

Facts set forth as organic parts of the whole picture—the living, functioning details of the entire complex social scene. That might be one of the most concise definitions of documentary photography. “America, to be interpreted honestly,” Abbott said, “must be approached with love void of sentimentality, and not solely with criticism and irony.”

Down at the bone, all photography is about editing—choosing what goes in and what is kept out, what to include in the frame and what to exclude. Abbott chose to include passion and exclude sentimentality; she chose to include “the living, functioning details.”

Berenice Abbott chose wisely.