He calls it ‘animal focused street photography.’ To me, that seems the perfect designation. What Giacomo Brunelli does isn’t really wildlife photography, though many of the animals he photographs are undeniably feral. It’s certainly not pet photography, although some of the creatures he photographs are undoubtedly somebody’s animal companion. And it’s not street photography in the traditional sense, though much of what Brunelli does takes place on the streets and it has the gritty, hard-boiled ambience we so often associate with street photography.

Brunelli appropriates the concepts, the approach, the philosophy of all those photographic styles and applies them to everyday animals. The result is something between art and documentation. Or maybe it’s the melding of art and documentation. Or perhaps it’s a refusal to separate art and documentation. Regardless, Brunelli’s photographs are distinctively his and immediately recognizable. That’s a rare thing in photography.

Giacomo Brunelli was born in Perugia, Italy in 1977. He has said that as a boy he played with animals, but I’ve seen no indication that he either owned a pet or felt any particular attraction to animals in general. Although his father was an amateur photographer, Brunelli doesn’t appear to have taken any special interest in photography until he was in college. He majored (and eventually took a degree) in international communications, but like most college students, he also stuck his toe into waters unrelated to his major. He took a course in photography and, using his father’s old camera, began to photograph the animals he saw on the street.

And that was that.

Brunelli still uses his father’s camera—a 35mm Miranda Sensomat bought in 1968. The Sensomat is a workhorse of a camera, fully manual of course, manufactured by a Japanese company in the late 1960s and early 70s. It’s a basic single lens reflex camera, but constructed so well that was often called ‘the poor man’s Nikon F.’ In other words, it’s a tank–a camera you don’t have to worry about dropping or getting dirty.

In a way, that 50-year-old old Miranda is the perfect camera for Brunelli’s work. The photographs have a raw and primitive feel, as if they were made in a less sophisticated, rougher, more hard-boiled time. They have an aura that reminds me of images made by combat photographers during the Second World War.

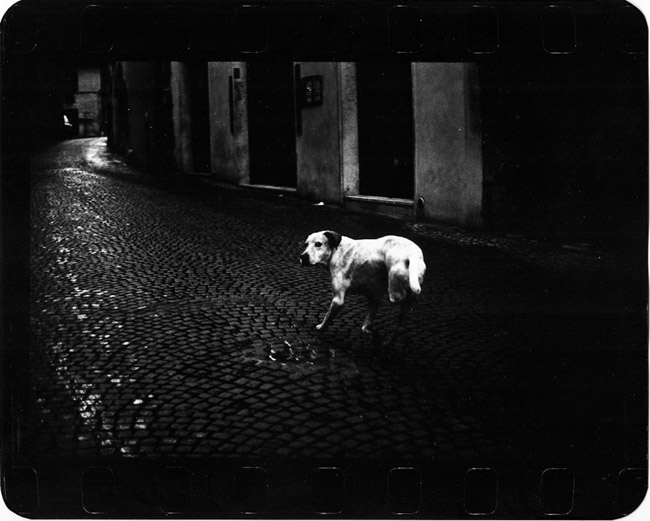

Brunelli’s process is as simple as his camera. He takes walks in the early hours of morning, before most people are up and about, when it’s just him and the animals. He seeks them out in city streets, in cobbled alleyways, in backyards and urban cemeteries; he wanders through nearby fields and barnyards.

“I only take pictures in the natural morning light. Once I see an animal that I want to photograph, I try to ignore it then I run after it which usually gains a response; sometimes I just stare at it and see what happens. Their reactions are different, sometimes they are curious about the camera and sometimes they get scared about the noise of the shutter.”

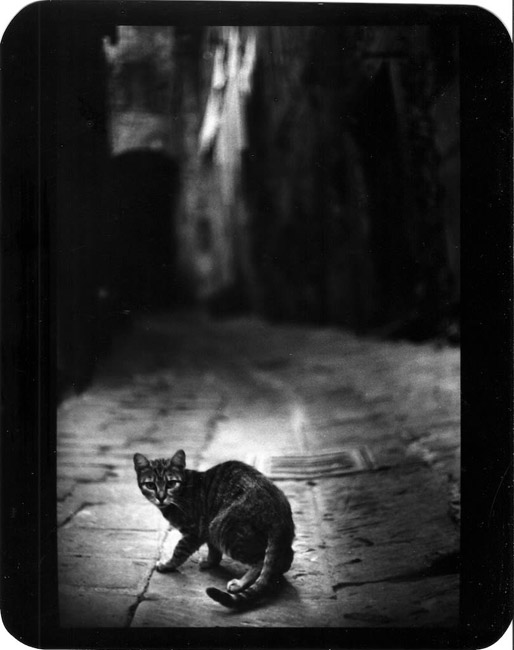

He likes to get low to the ground, on his knees or belly, down at the animal’s level. And he likes to get close, close enough, sometimes, to make the animal uncomfortable. Close enough to trigger a response. Brunelli doesn’t take polite photographs; like street photography his approach is often intrusive, provocative, even confrontational. Because of that, they’re sometimes uncomfortable to look at.

Almost every dog owner has seen a face similar to the one below. In all likelihood, this is an ordinary dog protecting its territory from an apparent intruder who refused to back off—an intruder who held a clicking chunk of metal and glass in the dog’s face. It’s an incredibly evocative image, and it’s hard not to have an emotional response to it. Regardless of how it makes the viewer feel about the photographer, it’s also a stark reminder that pets aren’t people. Even the most pampered pets—the most tame housecat and the most well-bred dog—they have lives that are unknown and unknowable to us.

The power of Brunelli’s photographs comes, I think, from three things. That early morning light, the angle of the photographer’s view, and the processing . The original prints of these photos were all processed in a makeshift darkroom.

Brunelli processes his prints with a sort of swashbuckling disregard for nicety. He’s not afraid of contrast, of creating dark somber images. He dodges and burns with panache, completely unconcerned at how obvious it may be to the viewer. He gets the final image he wants even if he has to grab it by the throat and slap it into submission. As a result, his photographs are imbued with a raw, primitive energy that strikes the viewer at a visceral level. Whether the photo is of a rooster strutting across the barnyard, a dog snarling at a trespasser, a three-legged dog, or a dove flying through an alleyway, Brunelli makes us feel something about the animal.

In a very real way, these photographs are heroic. We are reminded of how small and vulnerable are the animals we see every day, and yet, how resilient and adaptable they are. The street cat in the photo below—it will likely make its solitary way through the world, getting by on scraps and whatever other animals it can prey on. Or it will die, and probably die unnoticed. That snarling dog behind the fence—it might be a beloved pet whose ‘owners’ play with it, feed it a well-balanced diet, take it to the veterinarian regularly. Or it might be kept chained in the back yard in the summer heat and winter cold, fed table scraps, and never feel the touch of a kind hand. We don’t know, and we’re aware that both possibilities are equally likely.

The term ‘hero’ comes from a proto-Indo-European word meaning ‘to watch over, to protect, to save.’ Brunelli reminds us that in the end most animals—perhaps that cat, perhaps that dog—have to be their own heroes. They have to watch over and protect themselves.

I’m not sure you can call Giacomo Brunelli an animal lover. I suspect he is. He is certainly drawn to them. He clearly wants to explore their world. And just as clearly he wants his viewers to think about them, to consider how the world appears to them, to feel something about them. If he makes us uncomfortable, perhaps that’s a good thing.