Some people are confused by her name. Let’s clear that up quickly. Michal Chelbin is a woman. She was born in the Israeli city of Haifa in 1974, became interested photography at age 15 and attended a high school for the arts. After high school she served two years in the military—a mandatory service obligation for all Israeli citizens. She was assigned as a photographer to Dover Tzahal, the Israeli Defense Force unit responsible for information policy and media relations. There she gained experience in field photography and discovered she had no passion for pure documentary work.

After her military service, Chelbin worked briefly as a news photographer. She says she “hated every minute of it. I couldn’t photograph people in their grief, crying in hospitals or in courtrooms.” She soon left the field (“I was always late and eventually got fired“) and enrolled in a four year photography program at the WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization) Academy of Design. “It gave me the framework to start working on my own personal projects,” Chelbin has said. She’s been doing that ever since.

Chelbin’s artistic career appears to inhabit the border area between fiction and reality. She seeks out people (or groups of people) who, because of their occupation or lifestyle, exist largely outside of the mainstream. Gymnasts, dancers, circus performers, professional contortionists—people about whom a certain sort of mythos has evolved. She states her subjects “have a legendary quality in them, a mix between odd and ordinary.”

One distinguishing feature shared by all these various groups is the use of costume. When engaged in whatever activity that has drawn Chelbin’s attention—the dancing, the circus act—her subjects are always dressed for the stage. The importance of this will be made clear later.

Chelbin’s first major project revolved around large, traditional circuses in Israel and Europe, but in 2003 she turned her attention to small performance troupes and individual entertainers she found living in and traveling around Russia and the Ukraine. These circus acrobats, contortionists, and dancers became the core of a project that would eventually become entitled Strangely Familiar—the project from which the photographs shown in this salon were drawn.

Chelbin spent six years seeking out and photographing performers in small circuses and traveling troupes, primarily in Ukraine, Russia, and Israel. “When I started to work on my personal projects in Israel,” Chelbin told an interviewer, “the majority of people I photographed were immigrants who came to Israel from the former Soviet Union.” She says she liked their faces, and was intrigued by the ‘dark northern fairy tale’ aura of the region, so unlike her native Israel. It was only natural, then, that she would seek out that part of the world when her new project began.

Her process is very time-intensive. Chelbin spends weeks getting to know her subjects and their families, earning their trust. The time investment is necessary, partly because suspicion of outsiders is a common trait among such traveling troupes. That trust was especially important considering many of her subjects are children or teens.

There is a strangeness to child performers. In order to consistently perform well, they need to have an adult sort of discipline and focus. Many of Chelbin’s subjects perform acts that require extreme technical skills and intense physicality, acts that punish the body. It’s not uncommon to see their small bodies dotted with bruises and scrapes. All children, of course, routinely pick up scrapes and bruises, but those are generally earned through play—not through practicing a profession.

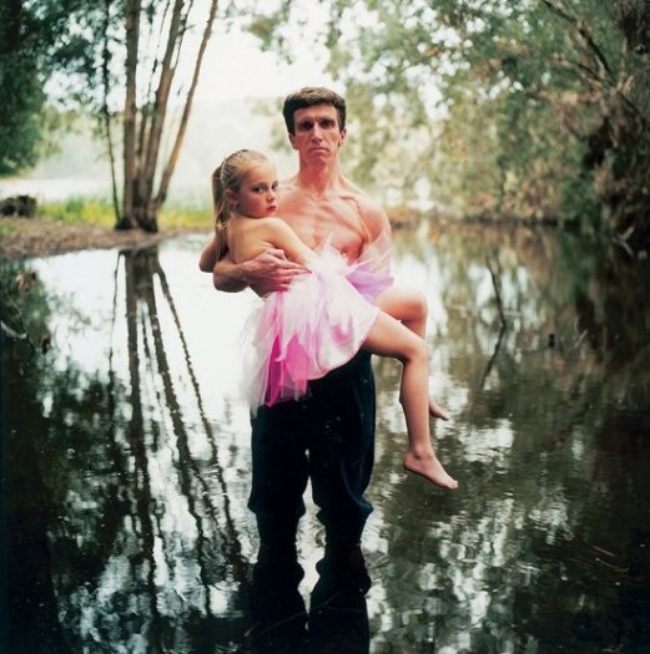

Although Chelbin photographs adult performers as well as younger ones, it’s always the portraits of children that draw the most attention. “As performers I think they mature very quickly,” Chelbin said. That contradiction—the maturity on the faces of her adolescent subjects—is compelling. Chelbin is drawn to that contradiction, and reinforces it in several ways. Since her subjects are taught to smile during their performance, she directs them not to smile. Since they generally perform on stage, she photographs them in casual, non-performance settings. Although she removed the subjects from the stage, she has them pose in their performance costumes.

The resulting images are models of incongruity. Unsmiling children with preternaturally mature sober faces clad in bright, glamorous costumes with theatrical make-up, all directly facing the camera. There is something almost disturbing about those faces, a sort of ‘children of the corn’ inscrutability that can make the viewer uncomfortable. On top of that is the strange confluence of performance and non-performance. These photographs are clearly posed; we are intended to look at them, an intention that’s underscored by the fact that the subjects are wearing their performance costume. Yet despite that, there is still a lingering sense of voyeurism. It makes one wonder if it’s possible to be a voyeur when the viewing is intended.

The voyeuristic discomfort is especially apparent in Chelbin’s photographs of young girls. She says many of the girls she photographs “are on the verge of sexual consciousness. They are in this difficult age, torn between innocence and experience. While their bodies might be still that of a child, their gaze sometimes imply differently. I try to create an informal scene, in which they directly confront the viewer.”

That confrontation is made all the more challenging when Chelbin includes an adult in the scene. The relationship between the child performers and their parents or guardians is complex, particularly when the adult is also a performer. According to Chelbin, many of the children who appear in her work come from broken families or were living in orphanages before joining a traveling troupe. Despite the colorful costumes and the allure of circus life, it’s clear the lives lived by these children are less than glamorous. What we see as costume, they see as their work clothes.

Technically, Chelbin’s work is relatively simple. She relies on natural light, uses standard film (Kodak or Fuji, 800 ISO for color and 3200 for black and white), relies on a single medium format camera (Hasselblad) with a single lens (I believe it’s a standard 80mm), and avoids digital post-processing.

She carefully stages her photographs, apparently selecting the setting for each photo based on the subject (including the subject’s costume), the available light, and the ambience of the space. Despite the staging, she remains open to serendipity.

“I am a great believer in intuition, in ‘happy accidents’ on the set, and in just going and taking photographs of something that interests you, without thinking about it too much.”

Her subjects sometimes make suggestions which she incorporates into the photo. “Girls usually like the attention of the camera,” she’s said, “and most of them enjoyed being photographed.“

Since the publication of Strangely Familiar Chelbin has moved on to other projects, none of which, unfortunately, have received the level of attention of that body of work. In a way, it’s not surprising. Her work on post-match exhausted wrestlers is intriguing and her images of women in water with goldfish are lovely and mysterious, but they’re not as emotionally moving as her earlier work.

Michal Chelbin may never produce work this absorbing again—not because of a lack of talent or imagination, but simply because it would be difficult to find any subject matter as viscerally compelling as the images we see here. It would, perhaps, be a mistake for her even to try. Although she is a serious photographer, it might be interesting to see her adopt a different sort of project. Chelbin has a whimsical nature that gets little attention. She has spoken of a project that exists only in her imagination: the glasses series. “It’s portraits of people who still wear funny old glasses,” she says. “Every time I see it I’m embarrassed to approach the person, so I think about this portrait in my head and add it to that series that was never taken.”

As much as I admire Strangely Familiar, I’d also like to see Chelbin shoot those photographs of people in old glasses. Taken with compassion—and I can’t imagine Michal Chelbin shooting without compassion—a series like that could be quite moving as well as amusing. She’s the sort of photographer who could make it work.