When he was eleven years old Andrew Miksys went with his parents to a bingo parlor, where a special session for children was being held. He won US$300.

“Overnight, bingo entered my life as this magical game that brought me treasure and the envy of all my friends,” he says. Bingo was, in effect, the family business; his father published a weekly flyer called Bingo Today. I assume as an eleven year old boy, Miksys paid as much attention to his father’s occupation as other young boys. Almost none, in other words. But hitting a big bingo his first night out apparently got him hooked—not so much on the game itself, but on bingo culture and the people who played it regularly.

Miksys, born in 1969, went to work for his father when he was in high school. He delivered Bingo Today to the various bingo venues in and around the Seattle area. All those institutional rooms, the rows of cheap tables, the elderly and the poor and the infirm and the lonely—all of whom sat in front of an array of bingo cards and good luck charms, listening to the litany of numbers being called out, marking their cards, waiting with anticipation for the chance to shout out “Bingo!”

Miksys took a BA in Liberal Arts from Hampshire College in Amherst, MA and an MFA in Photography from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Bingo halls were the obvious place for Miksys to start his career as a fine arts photographer.

These early bingo hall portraits show a delicate balance between honesty and empathy. Miksys doesn’t attempt to romanticize his subjects, but neither does he succumb to the temptation (which so many photographers give into) to make them seem grim or gritty in an attempt to show ‘reality.’ Despite the desperately unflattering lighting conditions of such places, Miksys manages to create a color palate that’s delicate without being faded or softened. It gives the photographs a slightly subdued, pale look—as if they’d been subjected to repeated laundering.

These are very humane portraits. Their defining characteristic isn’t passion, but affection. Miksys clearly likes these people—not necessarily as individuals, but as a group. He doesn’t treat bingo-players as a socio-economically deprived, semi-estranged subculture, but as people who share an activity. He seems to treat his subjects as if they were distant family members, people he’s prepared to like.

Miksys’ father was born in Lithuania, the southernmost of the Baltic states. Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Army near the beginning of World War Two, then occupied by the advancing German Army, and then re-occupied by the Soviets at the end of the war. The family fled in 1944 during the second Soviet invasion, eventually ending up in Seattle, Washington. In 1995, a few years after Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Union, Miksys’ father decided to return to his native land and visit relatives. Miksys accompanied him.

“I realized that it would be an interesting place to photograph. Lithuania was still a bit frozen in time. A lot of the villages hadn’t changed much in hundreds of years, and there were remnants of the Soviet Union everywhere.”

Three years later, armed with his cameras and a Fulbright grant, Miksys returned to Lithuania and soon found himself involved in shooting several loosely related projects. One of those projects involved candid photographs of bus passengers.

Of all of Miksys’ work (or at least of the work I’ve seen), the bus series is clearly the most mood-oriented. They can’t really be called ‘portraits’ and they can’t really be called ‘street photographs,” but they do much of what portraiture and street photography are supposed to do—they reveal something personal and intimate taking place in a public setting. Yet despite the public nature of the photos, they seem to be overtly about isolation—about being separate from others even while you’re amongst them. They are ambiguous and vague images, hushed, deeply melancholic and yet absolutely lovely. And as always with Miksys, people are at the heart of the image.

“I just wandered all through Lithuania,” Miksys said of his Fulbright year. While in Vilnius he shot some photographs of a family, and in the process discovered they were Romani—a group of people he’d known as gypsies. “For me it was super-interesting that they were real. You know, you see gypsies in movies, literature, but to meet real Romanic people is interesting.” A chance meeting turned into another long-term project, one which eventually produced a book entitled Baxt (a Roma term meaning ‘fate’ or ‘destiny’ or ‘luck’ depending on the context).

It’s a revealing title for a book of photographs about people belonging to an ancient, tradition-bound culture living in what had recently been a Soviet Socialist Republic. Roma people have been living in Lithuania for about 500 years without ever quite belonging to Lithuanian society. The Romani people are widely dispersed throughout the world, though mostly concentrated in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Anatolian region. Like the Jews, the Roma have a long history of persecution. (Coincidentally, just two months ago the government of France began a crackdown on Roma camps—demolishing more than 50 camps and expelling more than a thousand Romani from the country. That program of forced deportation is still taking place as this is written.)

Miksys somehow managed to overcome the Roma community’s suspicious attitude toward outsiders. They apparently sensed that he was genuinely interested in them, and they responded to that interest in much the same way as his Bingo players. “I think it helped that I gave people copies of the photographs I took of them,” Miksys says. “In almost any Roma home you’ll find family photos everywhere, and I think they appreciated this gesture. Now I’m often asked to photograph weddings and funerals in the Romani community.”

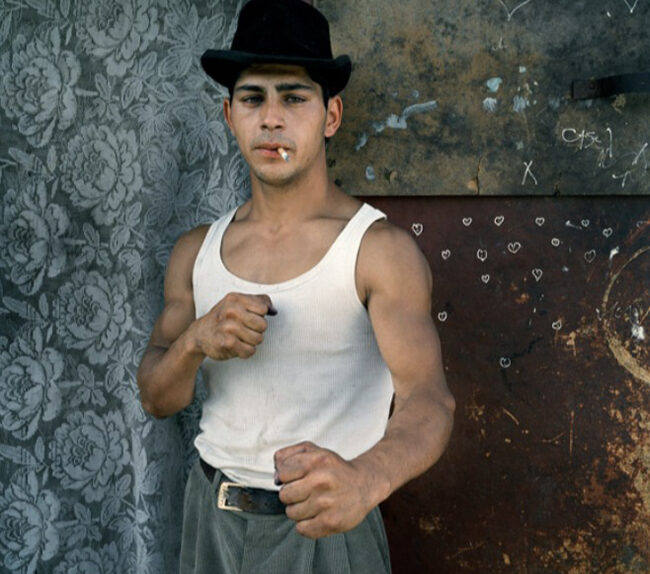

The photograph above provide a good example of Miksys’ approach to photography. Although he prefers to shoot portraits, he also photographs places. Not landscapes, necessarily, or architectural images—but places where people live and gather. Places that are shaped by and for human interaction.

“I had set my camera up to photograph the doorway of the house with the lace curtain and little heart drawings on the door, when Spartak stepped in front of my camera wanting to be photographed. I really liked the contrast between his tough guy poses and the flowered curtain and hearts. I ended up shooting several rolls of film.”

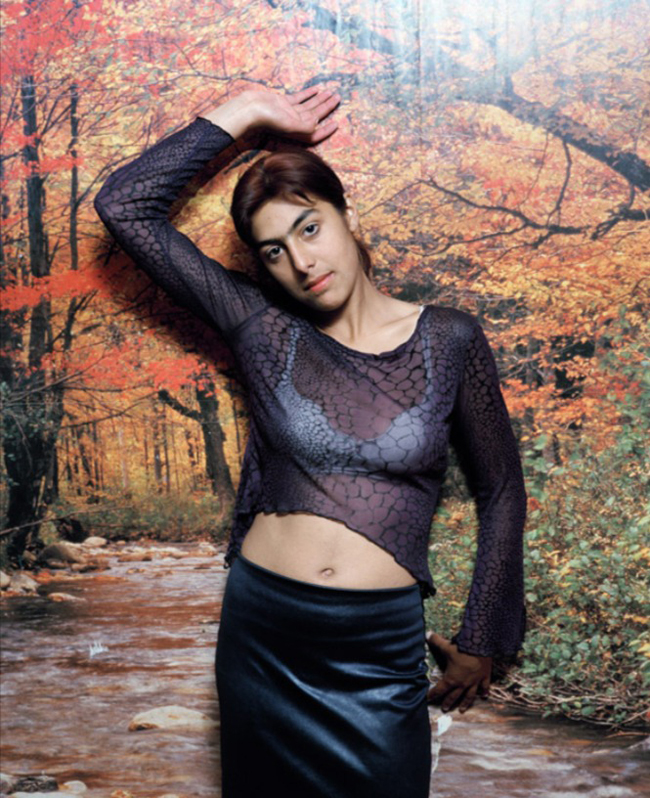

That toughness exhibited by Spartak (who is named for the gladiator Spartacus who led a slave revolt against Rome in 73 BC) appears frequently in Miksys’ portraits of young Romani men. The wary but defiant gaze, the clenched fists, the attitude—according to Miksys, they show up spontaneously when the young men agree to (or, in some cases, insist on) having their photograph taken. The young Roma woman he photographs also tend to reveal a form of defiance, though it comes across more in the form of a bold, sensual insolence. In each case, there is a general lack of concern—maybe even some contempt—for the conventions of dominant society.

Perhaps that attitude is borne out of a culture that is transient at heart, a society that is grounded in impermanence—a nurtured awareness that either by choice or the dictate of local authority they may at any time be packing up and leaving. Andrei Codrescu, who wrote the introduction to Baxt, notes that “the Roma were among the first Soviet citizens who were able to smuggle Western goods during socialism.” And yet, those luxury items never claimed much of a hold on them, possibly because they were merely another commodity for exchange, possibly because of a cultural heritage that stressed material goods might have to be abandoned when it’s time to move on.

In the end, Miksys’ photographs aren’t entirely about culture—not bingo culture, not Roma culture, not Lithuanian culture. They’re about people—people who, for the most part, are marginalized in some way, it’s true—but the emphasis is always on the people, not their marginalization. The settings may be cheaply-paneled bingo halls in New Orleans or barren Soviet-era cinderblock disco clubs in Lithuania (dating back to the era when the term ‘Cement’ was always capitalized because it was one of the ‘sacred materials of Stalinism’), but those settings never define the person standing in front of them. Even so, those settings are as much an aspect of the portrait subject as the clenched fists and cagey stare, as the curlers and the pack of cigarettes.

“When people get in front of the camera, they often assume some pose that represents the way they want to be seen in the world. I’m not photographing in the most glamorous places and I think many people I photograph see my camera as a way to transcend their environment.”

This is one of those instances in which I think the photographer doesn’t entirely understand his own work. I don’t believe the people in Miksys’ portraits are trying to ‘transcend their environment.’ I suspect they give their immediate environment about as much attention as a goldfish gives to the aquarium. It’s just the place where they happen to be.

Rather, I think Miksys photographs people in such a way that it elevates the environment in which they’re photographed. I believe that’s part of the peculiar genius of Andew Miksys.