I wonder, sometimes, if there is something about a childhood spent away from ‘home’ that instills in one a desire to travel. Sebastian Schutyser, for example, was born in the city of Bruges in 1968—but he spent his childhood in Zaïre (what was once called the Belgian Congo and is now the Democratic Republic of Congo). He returned ‘home’ to Belgium to attend the University of Ghent, from which he graduated with a degree in political science. Not long thereafter Schutsyer enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (also in Ghent), where he studied photography.

While I’m sure Schutyser shot lots of photographs in and around Bruges and Ghent, I’ve never seen any of them. Nor am I likely to. His work is centered elsewhere. It seems (to me, at any rate) his work features a fascination for the oddities of place—the sorts of things that would draw the interest of a Belgian child growing up in Africa.

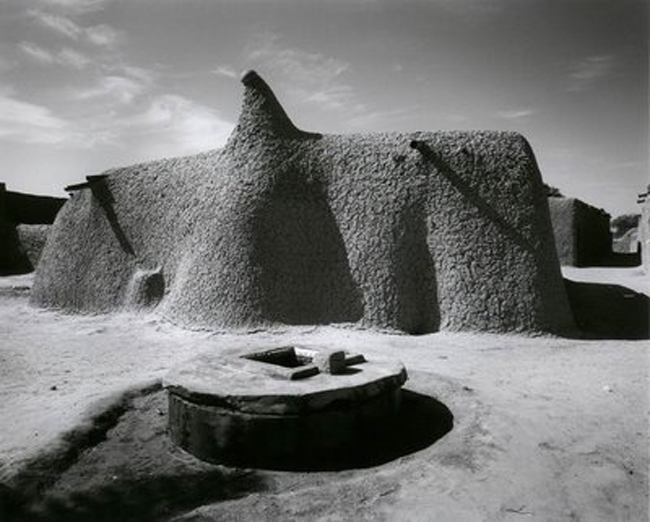

In 1996-97, while still a photography student, Schutyser spent several months traveling through Mali in western Africa. His intention, it appears, was to shoot portraits of the people of Mali. As he traveled, though, he found himself astonished by “the beauty of small adobe mosques in remote villages.” His interest in the vernacular architecture of these small mosques displaced his interest in portraiture. “So I decided to make an extensive photographic survey of the mosques of the Niger Inner Delta.” For the next several months he traveled the region, photographing over a hundred of the mosques.

By the end of that expedition Schutyser had created something more than a mere pictorial inventory of the adobe mosques of Mali. He’d begun an exploration into the association between human spirituality and the architecture of place. Those mosques weren’t just religious structures; they were an expression of locality. The skills used to build the mosques were local skills handed down from parent to child, the materials used were local materials. Each individual mosque was a reflection of the local community.

In the mosques of Mali, Schutyser seemed to have discovered his metier. His most important works (in my opinion) are images of remote indigenous architectural structures of a distinctly spiritual nature. After the mosques, he turned his attention to dolmen—those megalithic stone structures erected by early civilizations which are the first true works of architecture.

“The universality of the dolmen-concept establishes a direct link with an otherwise alien culture. Still their simple and pure beauty is exotic to me, and so are their natural surroundings. They are close by and far away.”

From neolithic dolmen Schutyser turned his attention to early Christianity. For the last seven years he’s been working on a series he calls Ermita—early Christian hermitages of rural Spain.

Today we tend to associate the term hermit with cranks—antisocial, misanthropic men who live alone, usually in some inaccessible region, where they grumble about civilization and eschew all hair care products. But the hermit is actually part of an ancient spiritual tradition.

The term itself comes from the Greek eremos, which is generally interpreted as meaning ‘solitary’ or ‘uninhabited.’ Eremites referred to people of the desert and the earliest Christian hermits did, in fact, retire to the desert. The notion was supported in part by the story of Jesus’ sojourn in the desert for forty days and nights, but the practice of self-isolation in remote regions in the search of a spiritual goal is almost universal. It’s not surprising that as Christianity spread into Europe that the tradition of the hermit was adapted to new surroundings.

Christian hermits in Spain are believed to have existed as early as the 6th century. By the 9th century, the practice was well established and, to some extent, supported by the Church. Some hermits lived in complete solitary isolation; others lived in small groups (typically twelve or thirteen—the number of the apostles of Jesus) which sought a closer relationship to the Deity by devoting themselves to silence, to penance through the mortification of the flesh, and to a life of prayer.

Structurally, the stone hermitages in which these hermits resided had nothing in common with the adobe mosques Schutyser photographed in Mali. But architecturally they shared some conceptual similarities. In each case, the structures are idiosyncratic while remaining rooted in the local culture. In each case, the buildings were representative of the people who built (or, in some cases, rebuilt) them. And in each case, the purpose of the structure shaped the design.

The earliest hermitages were products of the Visigothic kingdoms of Spain and their construction reflected that. Highly compartmentalized spaces, rectangular shapes, arches without keystones. Some were constructed under the auspices of the Church, some were built by the hermit(s) who lived in them. After the invasion of the Moors in the early 8th century, the architecture shifted to include Mozarabic influences (the Mozarabic peoples were those Christians who lived peacefully under the Islamic rule and adopted many of the elements of Islamic art and culture). During the period of the Reconquista, when Christian kingdoms fought to eliminate Islamic rule in Spain, the hermitages became less humble and architecturally were more a reflection of a conquering Church.

If one is sensitive to architectural style, it’s possible to see the political and religious transition of power in the details of construction and renovation of the hermitages. And yet despite the socio-cultural influences of the various religious-political power structures, these buildings managed to remain largely true to their original purpose—and that purpose is stamped architecturally on all of the hermitages.

Schutyser’s photographs again that these structures aren’t just piles of stone and mortar, just as the mosques of Mali were more than just adobe. He describes his photographs as “an attempt to reveal the genius loci,” which is a perfectly appropriate way to look at them. In classical Roman paganism, the genius loci referred to a guardian spirit—a magical entity who protected a specific location. We still use that phrase today, though we’re generally talking about the genius loci as a distinctive and unique atmosphere of a place.

There’s no doubt, looking at these photographs, that Schutyser has either found or created a unique sense of place. These are all strangely emotional images; they have the power of the land in them. In some sense, it’s not at all difficult to imagine the sorts of men who chose to live in these hermitages—and yet at the same time, it’s impossible to imagine what their lives must have been like. Long periods of isolation, voluntary or not, has a profound effect on the emotional and psychological well-being. In an era in which people feel isolated if the battery of their cell phone has died, the notion of spending years without anything but incidental contact with the world is staggering.

Schutyser chose to photograph the hermitages with a pinhole camera. It is “a poor man’s camera for the poor man’s church,” he says. And certainly the camera choice is key to the success of these images. They give each photograph the sort of clarity that comes from staring at an object of a long time, while also softening and blurring the world around the edges—an almost hallucinatory feel that one might get from long periods of isolation.

There is something contradictory at work here. Each hermitage seems solidly to belong exactly where it is, as if it’s rooted to the landscape. They seem both alien and organic at the same time. The almost complete absence of windows gives the buildings a sepulchral quality that’s often at odds with the open nature of the landscape. To live for a long time in such a building in such an environment would truly be a test of faith. And perhaps a test of sanity.

All photographs exist in the past, of course. But these feel like direct visions into a distant past, a time when the simplicity of daily life was bounded by the mysteries of the spiritual world. In these buildings men struggled with demons. We can be sure some of them lost that struggle; we can hope that most gained some sort of victory. But the fact that these structures exist is evidence, I think, that the struggle was sincere and even those of us who are unbelievers can respect the people who built and lived in them. And we can be glad there is a photographer willing to devote his time and effort to give us a glimpse into the past.

Nobody—possibly not even Sebastian Schutyser himself—can say whether his childhood spent away from his native home shaped his desire to visit remote places and photograph structures meant to be permanent spiritual holdings. But I like to think that’s the case. I like to think as a child he learned to see local architecture as a key to understanding the local people. Because in the end, it’s always all about the people.