There’s a small chain of islands located north of the Arctic Circle–about midway between Norway and the North Pole–known collectively as Svalbard (“the cold edge”). The islands are pretty much equidistant between Norway, Russia and Greenland, right at the juncture of the Norwegian Sea, the Greenland Sea, the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean. About 60% of Svalbard is covered by glacier. Another 30% is barren rock. Only about a tenth of the island chain is vegetated. There is no arable land. There are no trees. The only bushes that grow in significant numbers are cloudberry and crowberry. The average temperature in the summer is about 43 degrees Fahrenheit; the average in the winter is around 0 degrees. Because it’s located above the Arctic Circle the islands experience both polar day and polar night; for four months during the summer the sun never sets, and for four months in the winter it stays below the horizon.

Svalbard is not a welcoming environment for humans.

And yet humans have been going there for at least 400 years. They went there first for the whales–especially the bowhead whales. They were plentiful and, because they’re a slow swimming species whose bodies float after death, they were an ideal target for European whale hunters. The first settlements on Svalbard were built to house whaling crews and to process the blubber into oil.

When whalers discovered they could maximize their profits by processing the oil closer to their home ports, the whaling stations were abandoned. Aside from scientific expeditions to study the geology and the island chain’s plant/animal life, Svalbard remained largely unpopulated until the early 1900s. That’s when the massive coal deposits were discovered.

There had been international disputes over territorial whaling rights around Svalbard. The islands had no native population, and apparently nobody among the various whaling communities had thought to make a formal claim of sovereignty, which meant Svalbard essentially remained free of international control until around 1920. During the negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles (which formalized the ending World War One) it was decided that Svalbard would be ceded to Norway, although with certain unusual stipulations. Norwegian law would apply, but all citizens and all companies of every nation that signed that particular treaty would be allowed to become residents of Svalbard, and would therefore have the right to engage in any maritime, industrial, scientific or mining activity that didn’t violate Norwegian law.

Initially, only one nation took real advantage of the treaty: the Soviet Union. The Soviets established the community of Barentsburg on Spitsbergen (the main Svalbard island), and purchased an existing coal mining community (Pyramiden, named for nearby a pyramid-shaped mountain) from the Swedish government. These two communities became model villages for communism. Statues of Lenin were erected, ‘modern’ schools were constructed for the children of the workers, along with Soviet-style dining halls and housing facilities. In the 1970s the Soviets built a museum, a cultural center, a library, and a sports center with a massive indoor swimming pool. More than three thousand Soviet citizens lived and worked in Barentsburg. As they went about their daily business, they were greeted by a sign written in classic Soviet style: A miner’s hardworking hand yields heat and light for everyone.

Hardworking hands are an inexhaustible resource, but coal isn’t. Nor did Soviet-style communism prove to be a long-term self-sustaining system. As the Soviet Union collapsed, so did their communities on Svalbard. Pyramiden was essentially abandoned (although some 15-20 people continue to live there). While Barentsburg remains a working coal-mining community, fewer than 500 people continue to live there.

And this is where Norwegian photographer Christian Houge comes in.

Houge was born in Oslo, Norway in 1972. He obtained an International Baccalaureate degree from St. Clare’s, Oxford (the I.B. is apparently a sort of college preparatory program for international students). After graduating, Houge returned to Oslo and worked as a photographic assistant for a couple of years before becoming a freelance advertising photographer.

Over the last decade or so, Houge has also been making a name for himself as an art photographer with widely diverse interests. He has completed a project on the temples of Angkor in Cambodia, he has created a series exploring the nature of evolution, he has investigated the nature of dream and reality as expressed through certain Japanese subcultures, he has examined the relationship between Ophelia (the character from Hamlet) and water. And he has turned his large format panoramic camera on various aspects of Svalbard.

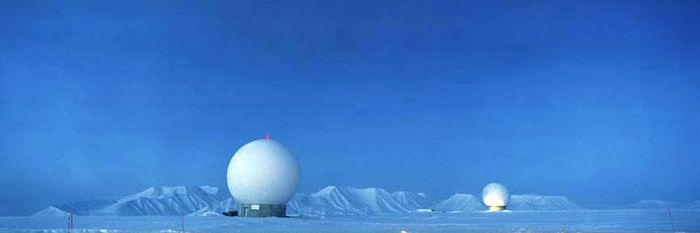

I’d originally intended to concentrate this salon on Houge’s project called Arctic Technology, a series of images depicting ultra-modern high-tech scientific facilities. Svalbard, because of its location and lack of population, has one of the cleanest atmostpheres in the world. It’s an ideal location for research in astronomy, in meteorology, in climate studies. Houge’s photographs of various antennae growing out of pristine snowfields are enormously arresting and beautiful in a science-fiction sort of way. They were the images that first drew me to Houge.

But I found myself drawn in more by his photographs of the very messy and very human failures of Barentsburg and Pyramiden.

Houge learned about Barentsburg and Pyramiden in 1983, during a snowmobile trip on Svalbard. He became intrigued by the melancholy air surrounding the communities. In his photographs of these small communities, one can still detect the 1970s-era Soviet confidence in their ability to impose their will on the environment. A tremendous amount of optimism and pride was invested in these communities. The collapse of that optimism and the crumbling of that pride is palpable in Houge’s photographs.

That’s especially clear in his photographs of the inhabitants of Barentsburg. There is an aura of weary isolation in those photos. They almost serve as a visual representation of Marxist alienation. Marx outlined four ways workers were alienated. First, they are alienated from the products they labor to create–in this case, the coal. Although coal provides heat for the community, the vast majority of it is shipped back to Russia. Workers have no input into what happens to the product, or its value, and they don’t benefit directly from its sale. Second, workers are alienated from the act of production–they serve the machine on which they labor; they are relegated to repeating a sequence of discrete, trivial motions that offer little, if any, intrinsic satisfaction. Third, they are alienated from the other workers–there is always competition for better jobs with better perqs and better pay. And finally, according to Marx, workers are alienated from themselves–by selling their labor, by working for a paycheck rather than for the satisfaction of the work, they have effectively turned themselves into objects whose value is determined primarily by their ability to perform a specific function.

Looking at the faces of the people in Houge’s photographs, you can sense the alienation. The people seem almost lost, as if they are strangers in a place they don’t really belong. Even when inside the buildings, the viewer is reminded that Svalbard is not a welcoming environment for humans.

In his Arctic Technology series Houge’s use of the panoramic perspective creates a sense of immense space, of vast natural vistas in which the massive antennae and man-made technologies seem small. In the Barentsburg photographs, that same panoramic perspective creates a cramped and pinched feeling. There is a sense of claustrophobia, as if a great weight is pressing down on the subject.

On top of that is the overwhelming suggestion of being cold–always cold. Cold and temporally out of place, trapped in time, locked into a faded and tainted Soviet Socialist empire that no longer exists. Look at the welder in the photo below–even his clothing seems pathetic; he looks like a refugee in some arctic dystopia. Mad Max of the North. He’s gazing at his pitted and corroded workspace with a sort of patient melancholy, aware that he’s using out-dated equipment to repair the collapsing structures of a slowly diminishing community devoted to obtaining a foundering fuel source for a nation in decline–and aware that it’s never ever going to get any better. How can you look at him and not have your heart break a little?

The Barentsburg photographs aren’t Houge’s most attractive or appealing work. But I believe they are the most human, and therefore–to me, at any rate–the most compelling. He manages to capture the frailty of human existence and at the same time, the human ability adapt to almost any situation or circumstance.

In the end, I think, these photographs are about audacity. We all like to celebrate audacity when it pays off, when somebody takes a risk and wins. But sometimes audacity ends in failure. If the failure is spectacular, we pay attention. But if the failure is a slow, inexorable sputtering out, we generally ignore it. Christian Houge has shown us an example of such a failure. And he’s found beauty in it.