I’m not going to be entirely fair to photographer Andrew Moore. Moore is a well-respected fine arts photographer whose work centers around the intersection of history and culture as manifested through architecture. He’s spent most of the last decade and a half creating brilliant images in such varied locations as Russia, Cuba, Vietnam, Bosnia and Abu Dhabi. And I’m going to completely ignore that amazing body of work.

Instead, I’m going to concentrate this salon entirely on Moore’s most recent series–images shot in Detroit. Over the last decade or so, Detroit has become something of a magnet for photographers who are drawn to urban decrepitude. There’s an excellent reason for that. In the first half of the 20th century Detroit was an economic powerhouse, one of the most prosperous cities in the United States. It was ‘Motor City,’ the heart of the American motor vehicle industry. That meant good union jobs with high wages for skilled laborers and excellent benefits.

Beginning in the 1960s, however, Detroit’s good fortune began to decline. Since then, the city has been ground zero for just about every social and economic problem imaginable. Rampant crime, racial riots, political corruption, de-industrialization, organized trade in illicit drugs, white flight to the suburbs, unemployment, home and business foreclosures. Wave after wave of cascading disasters have swept over the city.

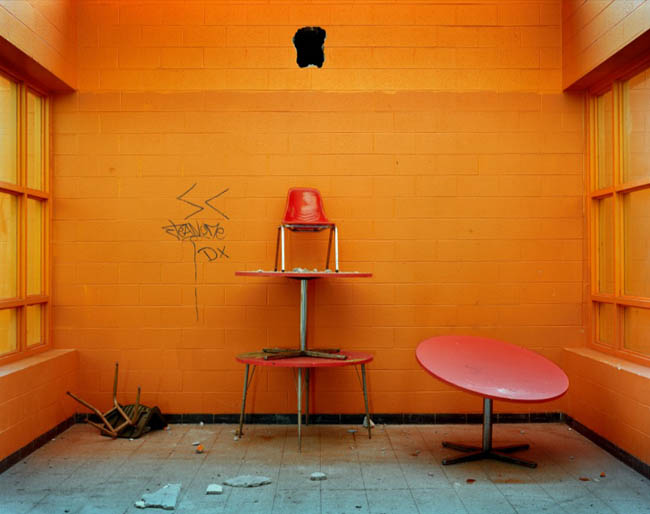

One result of all that was the abandonment of neighborhoods. Not just individual structures; entire neighborhoods became uninhabited. Poor neighborhoods, ethnic neighborhoods, working class neighborhoods, even some well-to-do properties. It’s estimated that something like 30% of the houses and buildings in Detroit proper have been abandoned. That’s approximately 90,000 abandoned properties–more than in any other U.S. city except post-Katrina New Orleans. Blocks of empty buildings, some slowly decaying, some rapidly falling apart, some burnt out, some in various stages of demolition, some just deserted. To give you an idea how devastated parts of Detroit are, the soon-to-be-released remake of the 1980s movie Red Dawn, which takes place in the rubble of an American city destroyed by a Chinese occupying army, was filmed partially in Detroit because it already looked properly war-torn.

Andrew Moore, born in 1957, has been taking photographs since he was twelve years old, and winning awards for his work since 1981. He studied at Princeton under Emmet Gowin and had his first solo exhibition in 1984. Although he’s been photographing New York City off and on since the early 1980s, Moore apparently had little interest in photographing American architecture–not because it wasn’t interesting, but because, as he says, “the United States may be the one of the toughest places to shoot in terms of finding new subject matter.” Everything in the U.S. has already been photographed. It’s all been seen already, in magazines, in movies, in books, on television shows.

However, while lecturing in Paris Moore met a pair of young French photographers, Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, who were fascinated by ‘contemporary ruins.’ This was a subject Moore had been exploring periodically since he’d visited Cuba in the late 1990s. Marchand and Meffre told Moore that if he wanted to photograph devastated buildings, he should forget Paris; he should go to Detroit.

“Detroit was a city that was assembled very quickly, and now it is unraveling at pretty much the same speed.”

So he went to Detroit, and found that Marchand and Meffre were correct. Detroit offered something Moore had never seen before. In his earlier work Moore had focused on old structures that were often re-purposed–for example, a Russian Orthodox church that had been converted to a Soviet soap factory, then in the post-Soviet era was being used as a youth center. The structures he found in Detroit weren’t being reused in any way; they were simply abandoned.

Hospitals, schools, libraries were just closed, shut down, and vacated. “The most disturbing part of photographing Detroit,” Moore said, “was certainly the schools–in so many of these elementary schools and middle schools, the books and the computers were just left.” Desks, chairs, blackboards, cabinets, bookshelves–all simply ignored and left to decay. Moore was appalled by the sheer waste of it all.

It is a staggering waste. Looking at Moore’s photographs one feels that the buildings weren’t the only things abandoned in Detroit. Hope seems absent as well, along with faith and any faint lingering aspiration for the future. In a way, the decline of Detroit can be seen as a morality tale, an allegorical warning to other cities. Former Detroit mayor Coleman Young said this: “Detroit today is your town tomorrow.”

Moore doesn’t consider his photography to be political, nor even documentary. Yet he acknowledges that the images have political implications. “I’m not really a documentary photographer,” Moore says. “I’m not trying to document decay. I’m looking for places that are meaningful.” Therein lies one of the conundrums for the fine arts photographer. Is it possible to photograph meaningful places or events and avoid politics?

“Is it art for art’s sake, or is art supposed to improve social conditions. I think those are irreconcilable aims. But I feel that the collision of those two things makes very interesting work.”

Interesting work. Those two words spark yet another issue. How can we find the evidence of the collapse of society as merely ‘interesting’?

Some people call it ‘ruin porn.’ Or ‘poverty porn’ or ‘disaster porn.’ All photography is an invitation to look. Attaching the appellation ‘porn’ to non-sexualized photography suggests an invitation to look at things we’re told we shouldn’t look at–things we’re told we shouldn’t even want to look at. It suggests a prurient interest, an indecent and unhealthy interest in observing the degradation or exploitation of somebody or some thing. It suggests that through the mere act of looking we are violating someone’s privacy or dignity, that we are titillated by what we see. It also indicates we are necessarily objectifying the subject.

This isn’t a new concept. James Agee (who wrote the text for Walker Evans photographic masterpiece Let Us Now Praise Famous Men) once stated that anybody who watched newsreel footage of the battle of Iwa Jima was degraded by the experience, because the film revealed “an incurable distance” between the viewer and the experience of the people being viewed. Susan Sontag, in regard to seeing images of violence or blatant sexuality, wrote “Once one has seen such images, one has started down the road of seeing more–and more. Images transfix. Images anaesthetise.“

And there is some truth in that. Some truth. We can look at the photograph below and we can be appalled or curious or fascinated or bored–but we cannot comprehend or appreciate the experience of the people who once lived there, who grew up there, who raised families there, who had supper at the table and slept in the beds and sat on that couch and watched television and one day walked out the door and never returned. We not only can’t comprehend their experience through that photograph, we often fail to even think about them.

But here is another truth: in order for us to label a type of photograph as ‘porn’ and in order for us to be offended by the accusation of a photo being called ‘porn’ we first have to feel strongly about the subject matter. Nobody is upset when an image of a lush orchid is called ‘flower porn’ or if a photo of a sumptuous chocolate pudding is called ‘food porn.’ But affixing the label ‘porn’ to something more substantial is sure to cause some offense.

And here is a contradictory truth: once the label ‘porn’ is attached, a judgment has been made–a judgment intended to dismiss or diminish the work in the eyes of others. If one feels strongly about urban decay, and argues photographs like those of Andrew Moore diminish the seriousness of the problem and ignore the realities of the lives of those who’ve suffered, then labeling the photographs as ‘ruin porn’ is meant to neutralize the photographs and dismiss them as unworthy.

The fact is, there is a long tradition of artists studying the ruins of society. Granted, the tradition is built on the study of the ruins of ancient societies, or societies in other parts of the world, societies belonging to other peoples–but the tradition is there. The etchings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich, the travel images made by Victorian photographer Francis Frith–they all created ‘interesting’ work grounded in the collapse of society. They all reveal facets of those extinct cultures that might not otherwise be known to us.

The only real difference is Moore’s photographs of Detroit artistically document the collapse of a still-existing society. Detroit may be in the process of resurrecting itself, but there is still a lot of necrotic flesh attached to its bones. I don’t think Andrew Moore is at fault for showing it to us. If we find the photographs offensive or disturbing, then the burden is on us to find a way to correct the circumstances, not to merely condemn the photo or the photographer.