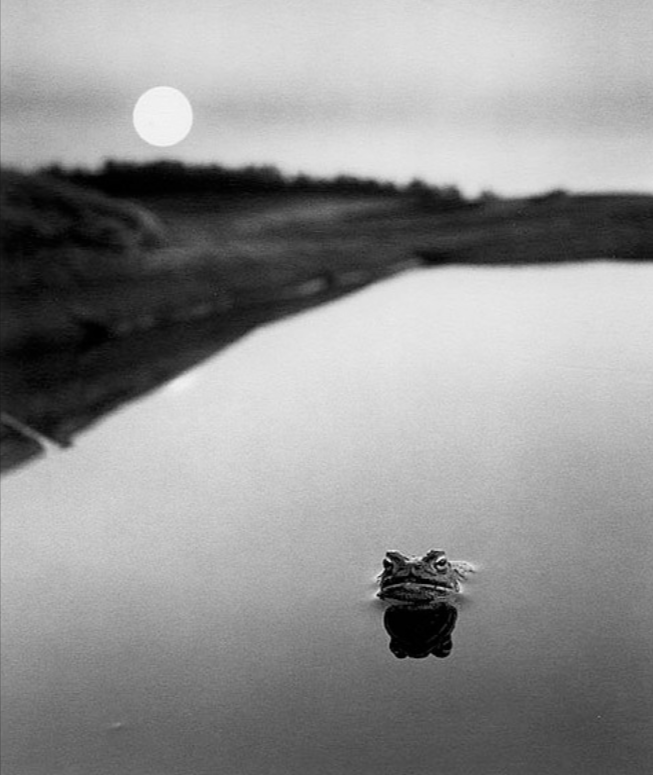

The photograph below was my introduction to Finnish photographer Pentti Sammallahti. I was completely charmed by it and immediately wanted to see more of the photographer’s work. I discovered that in some ways, this photo wasn’t necessarily representative of the scope of Sammallahti’s work; it’s very clearly manipulated in post processing and it features an amphibian (rather than a mammal). In other ways, however, it’s a classic example of his photography. It shows the stark landscape of Northern Europe, it utilizes a very clearly defined horizon line, the primary subject is an animal, and it displays a sense of compassion combined with a certain puckish sensibility.

Sammallahti grew up around photography. His grandmother, Hildur Larsson, was a photographer for a newspaper in Helsinki. He started shooting photographs at age eleven, joined the Helsinki Camera Club at fourteen, and had his first solo exhibition at twenty-one.

Sammallahti is one of those photographers who are engaged in the entire photographic process. He shoots the photographs, he develops the film, he prints the images. When creating an art book (which are usually done in small number limited editions), Sammallahti also designs the layout and selects the typography. He’s even been known to operate the rotogravure printing presses.

That sort of close attention to detail and quality pays off. As a result, Sammallahti (who had been teaching at Finnish universities for 17 years) was awarded an unprecedented 15 year arts grant from the government of Finland.

Sammallahti sometimes relies on a panoramic camera to capture the vast landscapes in which his subjects exist. flat, sparsely populated regions of Lapland, with their marshes and unending lines of pine forests. This perspective highlights the feelings of isolation and space, which often has the effect of creating the impression of hardy independence in both his human and animal subjects. By working almost exclusively in black and white, the ‘chilliness’ of the landscape is enhanced.

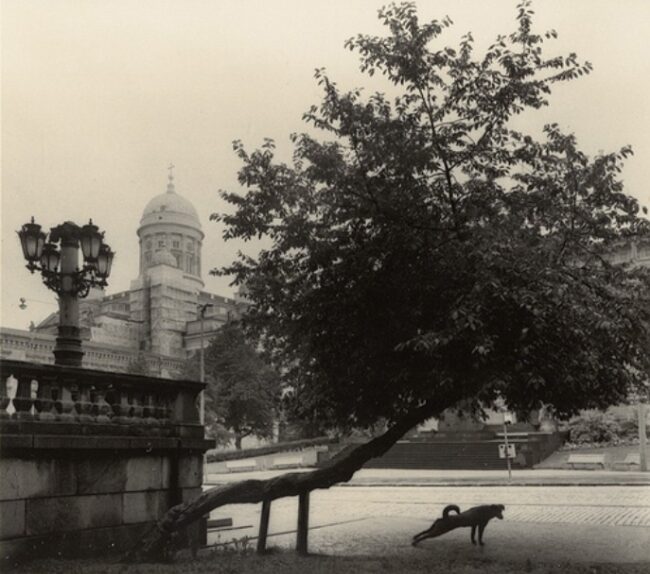

Since leaving the university Sammallahti has traveled more widely, taking photographs in the Welsh countryside, in Nepal, in Japan, in Turkey. Despite the radical differences in culture and environment in these locations, his work retains the same simple aesthetic, not to mention the same formality, the same charm, and the same delicate wit.

Much of that can be attributed to Sammallahti, of course, but I’d suggest his subjects also play a large role. A Japanese dog and a Scandanavian dog are more dog than nationality. They walk the same, they sleep the same, they stretch the same; their dogness matters more than the geography.

And that, for me, is where the real magic of the work lies. Sammallahti’s animals always seem to be going about their business in a matter-of-fact but still delightful way. One senses they’re moving through the frame, that they’re just passing by and in the next instant, they’ll be gone. And yet the landscape will remain, unchanging and unaffected and constant. That balance between the ephemeral animal and the eternal landscape is, I think, the key element of Pentti Sammallahti’s work.