Still life art has an ancient artistic tradition. Still life paintings have been found on the walls of Egyptian tombs; still life frescoes were uncovered on the walls of Roman villas in Herculaneum and Pompeii. Although the popularity of the still life has waxed and waned over the centuries, it has never become moribund.

Because of the control the artist has over the objects in the composition, the still life form can be used in an astonishing variety of ways. It’s been used in the service of religion, it’s been used as an expression of vanity, it’s been used to demonstrate both the glories and horrors of capitalism, it’s been used to make political statements for almost every political perspective imaginable, and it’s been used by students simply to learn their art and craft.

Photographer Olivia Parker’s work is very solidly in the still life tradition.

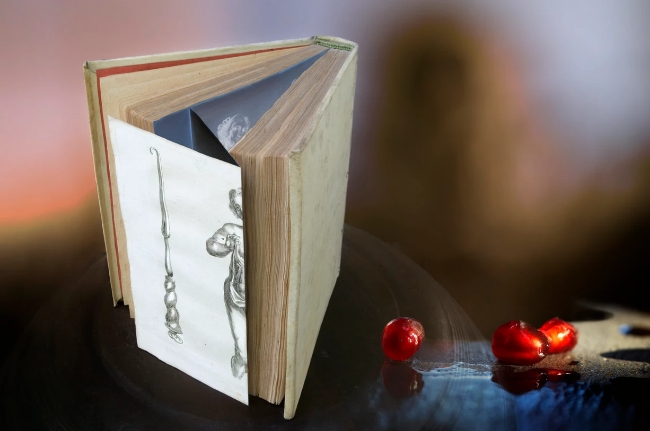

Like so many photographers, Parker began as a painter. She graduated from Wellesley College in 1963 with a degree in the History of Art. In 1970 she found herself moving away from the canvas and toward the camera. Her interest in photography was prompted by a fascination with natural light. Photography, she said, “is the only medium that demands light and natural light is always changing, transforming whatever is before out eyes.”

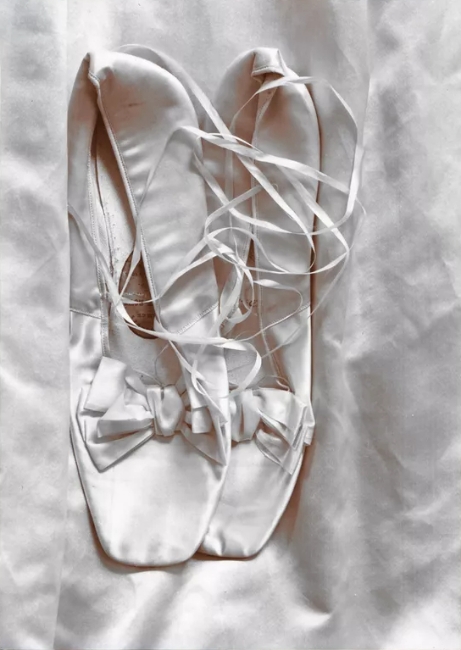

But why still life? If the spark of her decision to take up photography was the mutability of natural light, why concentrate on an area of art in which natural light is dispensable? Her reasons, it appears, are born in part from her study of the history of art. The persistence of still life art through the centuries, she says, “has to do with its proximity to the most basic concerns of human life: food; shelter; sex and accompanying life and growth; and death.” If that wasn’t reason enough, “[T]he simplicity of content in a still life allows for endless expressive experimentation within a form which remains close to universal human experience.”

As Parker’s photography grew and changed, so too did her understanding of the ability of an image to communicate a photographer’s ideas.

“At first I thought that good work had to communicate my exact ideas to an audience. I now know that every piece of art will communicate with each person in its audience in a different way.”

Taking photographs and looking at photographs are radically different acts. The photographer and the viewer each bring separate experiences to the image. Parker’s hope is that the Venn diagram of those experiences will overlap enough that some of the meaning imbued in the image by the photographer will be interpreted by the viewer. But hope and reality don’t always correspond.

In 1995, Parker shattered her leg in a skiing accident. Unable to work with a large format cameras in the studio, unable to spend necessary time in the darkroom, she began to experiment with computers and digital imaging software. Even though she continued to work in the very traditional still life genre, Parker felt no obligation to stay with traditional tools and techniques. She’s as comfortable in front of the computer as she is in the darkroom.

“In the beginning, view camera work was, however, a much better teacher for me than digital would have been. It made me slow down, consider image edges and think about the dynamics of what falls between the edges. Digital allows me total freedom to experiment without worrying about film usage or precise camera set up.”

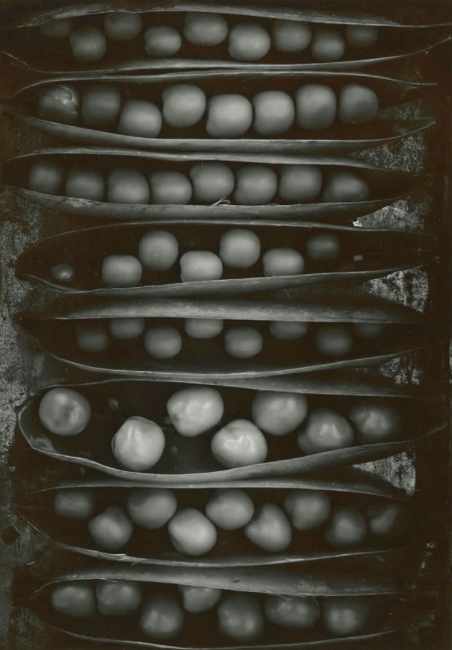

Her digital still life work combines elements of the traditional with elements of wild imagination–elements that are only made possible because of digitization.

Olivia Parker, working within what has often been considered a ‘small’ art form, has made big art. Throughout her career she has followed a vision that has been fluid within the given parameters of still life art, a vision that has been both malleable and yet entirely consistent. She has made images of heart-breaking simplicity and images of surreal complexity, and somehow all of those images retain the same sort of innocence, a guilelessness that finds fresh beauty in the ordinary world.