Over the last year and a half, in the course of preparing these salon discussions, I’ve done quite a bit of research on a lot of photographers. Not surprisingly, a lot of the same names kept turning up when those photographers discussed their influences. They’re usually well-known names, names most of us would recognize. But I also kept coming across one name with remarkable frequency–the name of a woman who was totally unfamiliar to me. Evelyn Hofer.

Several months ago, out of curiosity, I decided to find out who this Hofer woman was. There was surprisingly little information available on the internet. For the most part, the references I could find about Hofer fell into two categories. The most common references were just acknowledgments that she was the photographer for some project; a fashion shoot for Harper’s Bazaar in the 1970s, a writer’s portrait in the 1940s, a travel book by V.S. Pritchett or Mary McCarthy, an article in The New York Times Magazine. Almost as common were references buried in articles about other photographers who had studied with her, or worked as an assistant to her.

But there was very little information about Evelyn Hofer as a person, very little about her as a photographer, very little discussion about her own work. In other words, there was almost nothing on which to build an interesting salon. So I filed away my notes and moved on to photographers who were more ‘interesting’ and more accessible.

Still her name kept coming up. Then I came across the preceding photograph. And I stopped searching for information about Evelyn Hofer as a person and started searching for her work. Her work led me to the person.

Hofer was born in Marburg, Germany in 1922. When she was eleven the Nazi Party came into power and Hofer’s family fled to Switzerland. Shortly thereafter she decided she wanted to be a photographer. Hofer set about that career path methodically, with amazing determination. Her family arranged for her to begin an apprenticeship at the Studio Bettina, a portrait studio. She took private lessons with Hans Finsler, who was the first instructor at Zurich’s prestigious Kunstgewerbeschule. She later moved to Basel and studied under Robert Spreng, one of the pioneers of the “New Objectivity” movement (coincidentally, one of the forms of art labeled as “degenerate” by Hitler’s Nazi party).

Hofer’s studies covered everything from the most arcane aspects of photographic technique to art theory. She didn’t just learn composition and the underlying theories of aesthetics, she also learned the chemistry involved in producing prints. As such, she became one of the first photographers to adopt the use of color film as a normal practice.

After the war, her family moved to Mexico. There Hofer began her career as a freelance photographer. In 1947, she moved to New York City and quickly found work as an editorial photographer for Harper’s Bazaar. Hofer’s willingness to photograph anything and everything…editorial images, fashion photographs, corporate pictures…and the consistent quality of her work made her a valued freelance asset. Other New York magazines began to offer her work.

In the middle 1950s Hofer’s career took an important turn when writer Mary McCarthy asked her to provide the photographs for The Stones of Florence, a literary exploration of the history and culture of that city. Over the next forty years Hofer did the same for several well-known writers who produced books on Spain, Dublin, New York City, London, Paris, Switzerland, Washington, DC.

Her methodical training as a young woman appears to have prepared Hofer to undertake any sort of photography in any sort of circumstance. She proved to be equally at ease shooting gardens in Paris and gravediggers in Dublin, as adept at photographing fashion models in New York as she was at shooting ruins in Rome.

Hofer quickly earned a wide-ranging reputation for producing exquisite commercial photographs with reliability. What’s amazing is that she retained that reputation through four decades. She shot photographs for an astonishing variety of newspapers and magazines: Vogue, House and Garden, The London Times, Vanity Fair, Time-Life Books, Harper’s Bazaar, Connoisseur, The New York Times, Life. Her reputation was not that of an artist; it was that of a brilliant and dependable professional photographer.

Some portion of Hofer’s success is due to her grounding in art theory as well as in photographic technique. Although she was exposed to many theoretical approaches to art during her training, her mentors were proponents of the New Objectivity art movement. That school of thought emphasized works that were almost clinically realistic yet full of emotional intensity (as opposed to, say, Expressionism in which absolute realism is either unnecessary or possibly even a barrier to understanding). Clearly, the New Objectivity school influence Hofer’s work.

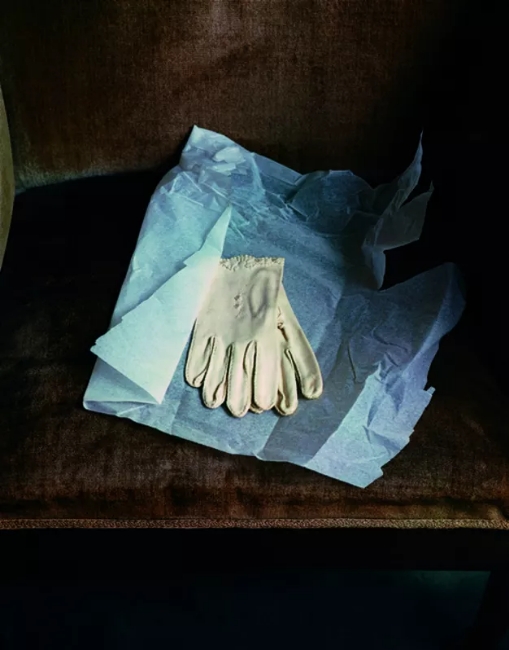

Take, for example, the following photograph of a pair of gloves owned by the poet Marianne Moore. It’s a deceptively simple image. It’s just a pair of white gloves sitting on some light blue tissue paper placed on a dark brown table–but there is something moving about them, and that emotion is sparked by more than just the lighting. It also comes from the progression of color from light to dark. It may also come from the progression of materials from soft to hard. It certainly comes in part from the suggestion that these gloves are being revealed to us, that the tissue paper has just been unfolded and that we’re being given a peek into something personal and intimate.

Those gloves could be photographed in a hundred different expressive ways. That Hofer chose this way, so perfectly in keeping with the New Objectivity school, is almost certainly not an accident. By arranging the lighting and the subject in a specific way, she deliberately created an image that depicts the subject realistically while evoking a strong sense of emotion. One needn’t know anything about Marianne Moore to appreciate the emotion of the image.

Evelyn Hofer wasn’t a pioneer of photography, but she was one of those critical photographers who took the work of pioneers and made them commonplace and conventional. She wasn’t an art theorist, but she was familiar with various schools of art and understood how to apply the theory. She didn’t shoot iconic photographs, but she took young photographers under her wing and trained them to be technically proficient and artistically flexible. She wasn’t an innovator so much as she was an advocate of innovation.

She has been called “the most famous unknown photographer in America.” I rather think she’d be pleased with that title. As a professional photographer, she understood that the work is what mattered, not personal fame. As a teacher, she understood that it was passing on knowledge that mattered, not passing on a cult of personality. My guess is that Evelyn Hofer is satisfied to let her work–and the work of her students–speak for her.