We all have them. Irrational beliefs, odd compulsions, unwelcome and intrusive thoughts, strange anxieties, illogical fears. Even the most emotionally healthy of us experience these things. They are ubiquitous and pervade almost every aspect of our lives.

As improbable as it sounds, Sarah Hobbs photographs them. It could be said she photographs them obsessively. She carefully constructs an elaborate set fashioned to represent some aspect of human psychology—a physical manifestation of an emotional state—then photographs it with a large format camera. It’s a slow, slow process involving a number of labor-intensive steps. It requires her to meld creativity with tenacity and deliberation, as well as a lot of heavy thinking and hard work.

Consider insomnia. Most people in modern societies have experienced difficulty sleeping or some form of sleep interruption, often as a result of stress, anxiety, tension. No matter how weary you are, no matter how sleepy, the moment you close your eyes your mind is beset with all the things you have to do, all the things you’ve left undone, all the things you should have done, all the bad decisions you’ve made, all the worries and cares you could ignore when you were awake and busy.

Hobbs represents those undesirable and unwanted thoughts using Post-It notes, suspended menacingly just above the pillow, closing in on the poor person who’s been struggling to sleep, intruding into the comfort of the bed. The would-be sleeper has been driven from the bed, the sheets and coverlet tossed wearily aside. There is no room for sleep here.

There is something intensely personal about these photographs, and yet they’re also universal. Almost everybody can relate to the complex emotional states the photographs represent.

“Everything always comes back to the viewer. The psychological issue is presented in the photograph, but it’s up to the viewer to contend with the space in their own mind and bring their own psychological make up to it.”

To reinforce the psychological intensity, Hobbs makes large prints, four feet by five feet. The scale of the image when seen in a gallery or museum lures the viewer to assume the role of the person implied in the photograph. The notion of the Implied Person is central to Hobbs’ work. No people actually appear in her photographs, but each image holds the suggestion of one or more people.

Take, for example, her photograph Overcompensation. The empty chairs hold the insinuation of the room’s occupants. The room is so full of gifts that there’s almost no room for people, suggesting that the giving of gifts—the number of gifts, the size of the gifts—is more important than the person receiving them. What’s inside the gifts is less important than the number of gifts. The gifts say nothing at all about the person receiving the gifts; it’s all about the giver and the giver’s psychological state. Although there is a sense of opulence about the room, it is otherwise empty, emotionally sterile. There is an emptiness–an emotional void–that the giver is attempting to fill with gifts.

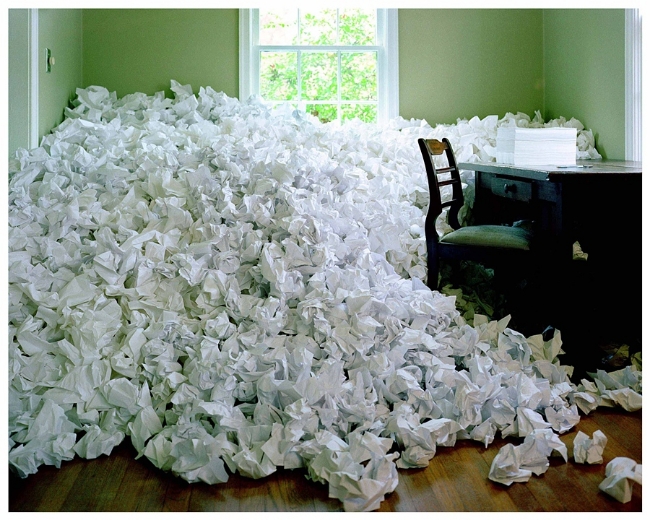

One recurring theme in Hobbs’ work is the notion that the psychological subject of the photograph crowds out the Implied Person. The emotional state being examined in the image overwhelms the person experiencing it. In Indecisiveness, the act of trying to pick a paint color has become a nightmare. There are so many paint swatches, so many choices, that it’s become impossible to select only one. The Implied Person has fled the room, closing the door, opting to make no choice at all—which, in the end, is a sort of negative choice.

Hobbs takes great care in selecting the space in which to construct her installations. Initially, she staged all the photographs in her own home. Now she searches out particular sorts of spaces for her images. “I like to do them in actual spaces and actual homes,” she says. She generally comes up with an idea to represent a specific psychological state, then seeks out a space that supports the idea. “I have to be open-minded about the spaces I find…if I try to make [the space] fit my first idea, I think I would probably make myself crazy.” In most instances, the space itself is a comfortable space; the installation she sets within the space makes it uncomfortable.

Hobbs deliberately includes her personal title for the photographs in parentheses while insisting they are actually untitled. Her title, she says, “is just a jumping off point. I am talking about something specific in each of these images, but there are other feelings that permeate” the photograph. In a very real way, each viewer can give the photograph a personal title depending on what emotions the image evokes in them.

Just as there is an Implied Person in each photograph, there’s also an implied narrative that must be completed by the viewer. For example, Hobbs’ image of perfectionism contains elements that will be interpreted differently by different people. One person might focus on the sense of frustration that comes when one has a good idea but can’t quite get it right in trying to implement it. Another person might see a struggle, a refusal to give up that could be interpreted as either heroic or delusional. Even in the face of a tidal surge of failure, the Implied Person continued to grapple with the idea.

One of the most difficult aspects of Hobbs’ work is the sheer amount of invisible labor involved in the conceptualization–the process by which she decides how to compose an image that depicts the psychological state she wants to explore. She admits she’s not always successful. For example, Hobbs confesses she has tried several times to create an image of anuptaphobia—the pathological fear of never marrying or marrying the wrong person—without success.

Hobbs has undertaken what may be the most difficult form of conceptual photography. She tries to create a universally comprehensible physical manifestation of a complicated and highly individualized emotional state. Anuptophobia may elude her for now, but her ability to reify the abstract and her compulsion to express herself suggest that she’ll eventually find some way to mold it into a photograph. It’s the singular genius of Sarah Hobbs.