Harold Evans, editor of UK’s The Sunday Times, recounts an incident that took place during a routine firefight in some nondescript zone of conflict in some obscure corner of the globe. People were screaming, gunfire was rattling, everybody was running and ducking for cover…and Don McCullin stopped long enough to take an exposure reading. Afterwards he said, “What’s the point of getting killed if you’ve got the wrong exposure?“

Moments like this are the reason McCullin occupies a legendary position among conflict photographers. Photojournalists who cover wars, conflicts and disasters are a pretty jaded lot. They’ve seen it all, heard it all, done most of it, and they’re not easily impressed. McCullin–his photographs, what he went through to get them, and what’s happened to him as a result–impresses them.

The conventions of war photography were established during the Spanish Civil War, when smaller cameras allowed photographers to get close to–and into–the action. The technologies of both photography and war have changed in the intervening years, but the attitudes of the people who use them have remained virtually unchanged. Get close, get the photographs, get away. Says McCullin,

“This may sound ridiculous, but I know that I have a perception of coincidences which has allowed me to get close to certain situations and come away alive.”

Note that he says ‘alive,’ not unharmed, not undamaged.

McCullin became a photographer largely by accident. He was born in 1935 in a working class neighborhood of London. The entire family lived in two rooms, no kitchen, no bathroom. In 1940, during the Blitz, five year old McCullin was evacuated to a farm outside a small town in Somerset. As a poor boy and an outsider, he was teased and beaten by the children of the town. The family with whom he was housed also beat him. He was only allowed to attend evening church services; it was apparently felt he wasn’t fit for the morning or afternoon services.

At the end of the war, McCullin returned to his family in London. His troubles didn’t end there. He did poorly in school (as an adult he discovered he was dyslexic). Despite his bad grades, his ability to draw earned him a scholarship at the Hammersmith School of Arts and Crafts and Building. However, his father died when McCullin was 14 and he had to leave school and find work. He took a position as a pantry boy for a railway line, then later became a messenger for an animation studio. He was called up for national service and joined the Royal Air Force, where he was assigned to be a photographer’s assistant. Initially his duties involved painting numbers on film cannisters containing aerial reconnaissance film from WWII. He failed the written examination to become a photographer, but eventually was promoted to work in the darkroom.

While in the service, McCullin bought a Rolleicord camera, an investment of £30. After his period of service was ended, he returned once again to his poor neighborhood of London and his job at the animation studio. He ran around with a rather rough crowd of Teddy Boys–a gang calling themselves the Guvnors–and occasionally took photographs of them. Needing cash, however, he pawned the camera for five pounds. Fortunately, his mother redeemed the pawn ticket and gave him back the camera. A few weeks later, some of the Guvnors got in a fight with another neighborhood gang. A police officer tried to intervene and was stabbed to death. The crime received a lot of attention in the press. At the suggestion of some of his co-workers, McCullin took his photos of the Guvnors to the editors of The Observer. They bought a few of the images, and began to give him other freelance work.

By the middle 1960s McCullin was working fulltime as a photographer. He was hired by The Sunday Times and given plum assignments. He was soon something of a celebrity photographer. He photographed the Beatles, he visited Cuba with Edna O’Brien, he was hired to do the photographs for Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow Up. It was a happy time for McCullin. He married, started a family, enjoyed life.

Then he covered his first war: the Cyprus conflict in 1964. In Cyprus he began to shoot the photographs and collect the memories that would come to consume his life. He photographed the fighting in the streets and the victims of that fighting.

“A shepherd had been murdered, and I walked into this house and I photographed a boy brushing flies off of his dead father’s face…and I remember the smell of the coffin and the candle burning in the room.”

After Cyprus came the Congo, and Vietnam, and Cambodia, and Israel, and Biafra, and Venezuela, and Northern Ireland, and Zimbabwe, and El Salvador, and Czechoslovakia, and Uganda, and Lebanon. For the next two decades McCullin covered every major and minor war, every genocide, every revolution, every famine or disaster that popped up anywhere in the world. He once said he used to chase wars like a drunk chasing a can of lager.

“In the beginning, I used to shoot a few pictures and run away, thinking ‘I’ve got the story.’ In the Six Days war, I stayed the one day of the battle for Jerusalem and left the next day. Then I realized that I should never run away, until the thing was finished. And I stayed longer, and longer, and longer. In the citadel of Huế, in 1968, I stayed for two weeks.”

That’s two straight weeks in one battle, longer than most of the Marines who fought in the battle. It was during those two weeks that McCullin entered the realm of photojournalistic legend. Many of his most iconic images were snapped in those two weeks in Huế.

McCullin not only remembers each horrible moment of those conflicts, he can recall the shutter speed and aperture for each photograph.

“I took a picture of a grenade thrower. It was a 250 f8, because he was throwing a grenade, and I still managed to stop the hand grenade in the air. Except in the split second after I took the picture, a bullet completely destroyed his hand. He had a hand like a cauliflower, and he was weeping, and I photographed him crying.”

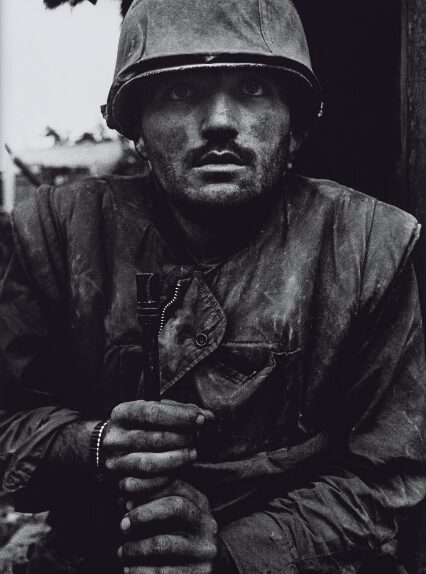

During that same battle McCullin shot a photograph that captured the human cost of combat–a Marine who’d seen too much, done too much, slept too little, and knew he’d soon have to go out and do it all again. In the Second World War they called that an emotional state the thousand yard stare. It was once illustrated by a painting done by combat artist Tom Lea in the Pacific Campaign of the Second World War. McCullin’s photograph is universal and timeless, and emotionally stunning.

Each war, each conflict, each revolution, each famine led him deeper into darkness. Each left him with scars, both physical and emotional. In the Congo, where journalists and photographers had been forbidden to leave the capitol city, McCullin ignored the order and was captured, beaten, and escaped only through the intervention of the legendary mercenary leader ‘Mad’ Mike Hoare. In Uganda he was captured by Idi Amin, imprisoned and beaten, and eventually expelled from the country. His wife was mistakenly informed he’d been killed. He and French journalist Gilles Caron hid in a doorway in Beirut, watching while Christian Phalangists executed Palestinian civilians in the street. A couple years later Caron would be captured and killed by Khmer Rouge in Cambodia around the same time McCullin was caught in an ambush a few miles away. During that ambush McCullin, forced to take cover in a rice paddy, kept his body in the water while he held his Nikon in the air, shooting several photographs before the camera was hit by a round from an AK47. A few days later he was wounded during a firefight–shrapnel in the legs and crotch, ear drum blown out. Knowing what had happed to Gilles Caron a short time earlier, McCullin crawled nearly half a mile on his stomach to escape the Khmer Rouge. In El Salvador, while scrambling over rooftops with rebel forces, he fell and broke his arm in five places.

It was in Biafra, where he traveled the day after his third child was born, that McCullin had what he called “one of the worst days of my life.” He described it to an interviewer:

“[S]eeing eight hundred children dropping down dead in front of me, crawling around on their stomachs with their insides hanging out…can you believe that? There’s a special medical name for it. You see them crawling around with flies on this great mass of interior flesh.” (The condition, by the way, is called rectal prolapse.)

In 1982 McCullin found himself back in Beirut, where the civil war continued to rage. By that point, nearly every one of the half dozen different belligerent forces–the Israelis, the Syrians, the Lebanese Front, the PLO, the Lebanese National Movement–had, at one time or another, joined forces and betrayed each other at least once. Nobody trusted anybody. McCullin had just finished shooting an astonishing series of images of fighting in a shelled-out former mental institution when he saw a Palestinian woman fleeing a bombed out building. As he started to photograph her, she noticed him–and attacked him. Her family, it turned out, had just been killed. She herself was killed by a car bomb a few hours later. “That blow made me understand that my time was up,” McCullin said, “that I had to get away from these situations.”

Although he made a short foray into Iraq in 1991 (McCullin stayed out of the action but “one of my friends trod on a mine and got himself killed“), Beirut was his last war.

A year after McCullin left Beirut and turned away from war photography, a new editor took control of The Sunday Times–the newspaper that had supported him for eighteen years. The new editor was more interested in what McCullin called “style pieces and garden furniture” than in the sort of grim, serious work to which McCullin had dedicated himself. He soon found himself out of a job.

McCullin settled in a house in Somerset, not that far from the town to which he’d been evacuated as a boy. He continues to shoot photographs. War, combat, genocide, famine–those themes no longer dominate his work, but he remains rooted in conflict and darkness. He shoots homeless people and derelicts, or somber still life images, or bleak winter landscape scenes.

“I look forward to evening light, and the naked trees when I go out; and I live in this Arthurian world of Somerset. And you know, I lay it on a bit thick, I know I do, but I really like working with angry clouds and naked trees and English hedgerows.”

McCullin keeps a small studio in his home, where he keeps the prints and negatives from his half century career. Those photos and his residual guilt have made him anhedonic. He appears unable to experience pleasure from normally pleasurable activities. The guilt weighs heavily on him. Those wars and those pictures have never left him.

“My house is full of pictures of devastation and pain and suffering. I published a book a few years ago and I called it Sleeping with Ghosts because I know that when I’m in my house and I’m down at one end of it asleep, down the other end there’s all these filing cabinets with this raucous noise going on down there. I mean, obviously it sounds to you like I’m barking mad, but I’m not…there is some mischief going on down where those filing cabinets lie. You can’t have that material, that energy in a house without something going on down there.”

What Don McCullin has done with his life is astonishing and important. What his life has done to him is terrible and important. What we’ve gained from that life are images of stark horror, unbearable suffering, monstrous inhumanity, and intense compassion. It’s horrible, but important. The novelist John le Carré once said he’d rather watch any amount of television battle footage than have to leaf through just one of McCullin’s books of photography. He said that in the preface to one of those books, because he couldn’t help but look.

It’s important to look.