Is he a street photographer? Yes. Is he a documentary photographer? Yes. A photojournalist? A travel photographer? A portraitist? A fine arts photographer? Yes, yes, yes, and most certainly yes.

French photographer Marc Riboud isn’t easily categorized, because he’s never specialized in any particular area of photography. After half a century of shooting, there are some recurring themes and stylistic idiosyncrasies, but the work itself falls easily into half a dozen different modes of photography. Riboud has been shooting highly personal images that appeal to a variety of markets. The marketplace, however, has never been uppermost in his mind.

Born in Lyon, France in 1923, Riboud became interested in photography at an early age. His father, a combat veteran of the First World War, gave him the dented little Vest Pocket Kodak that he’d carried on the battlefield. It seems Riboud was initially as intrigued by the personal history of the camera as he was by the act of photography. “The camera stirred my imagination,” he wrote, “for it had its own story to tell: it had witnessed the mud and the courage, the suffering and the absurdity of the trenches.” In a very real way, that attitude epitomizes Riboud’s photography; his work is about personal stories as interpreted through the camera.

The Second World War came to France when Riboud was seventeen years old. He joined the French Resistance movement as an active member of the Maquis du Vercors and took place in several engagements. After the war ended, Riboud enrolled in Lyon’s Ecole Centrale, where he studied engineering. After graduating, he accepted a position at a factory in the nearby town of Villeurbanne and began a normal life. His interest in photography, however, hadn’t diminished.

Riboud took a week-long holiday from his job to attend (and, of course, to photograph) a drama festival held in Lyon. That week-long holiday never ended. Perhaps the time he spent fighting with the Resistance made the regimented life of a factory engineer intolerable, perhaps he felt his position didn’t permit him enough of an outlet for self-expression, perhaps he went insane—we don’t know. What we do know is that instead of resuming his safe and secure career, Riboud never returned to his job. Instead, he decided to devote himself to photography.

Riboud moved to Paris, where he had the good fortune to meet another photographer, also a veteran of the war: Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson and his partners had founded the Magnum photography agency shortly after the war. He encouraged Riboud to keep working at his photography.

Riboud learned he could actually sell the photographs he would have taken anyway. In 1953 LIFE magazine bought one of his early photographs–a man applying a coat of paint to the Eiffel Tower. That photo became one of Riboud’s signature images. It contains all the elements that characterize his style: an emphasis on graphic composition that works in balance with the human figures, who are always depicted with compassion.

That photo also earned him an offer to join Magnum as a member. The unique approach of the Magnum agency allowed Riboud to shoot the sorts of photographs he wanted to shoot, while giving him a grounding in the actual business of photography.

Although his work for Magnum encompassed everything from photojournalism to portraiture, Riboud never approached an assignment or a project with a personal political or social agenda. According to Riboud, photography “must not try to be persuasive. It cannot change the world, but it can show the world, especially when it is changing.”

With the support of the Magnum Agency, Riboud documented a lot of change. For the next few years, from 1955 to 1960, he found his way through India, Nepal, Mongolia, and the Soviet Union. He drove a car from Alaska to Mexico, shooting photographs as he went. He became one of the first Western photographers to be allowed into China after the Cultural Revolution. Later he would document rebellions and civil insurrections and wars in Africa, Southeast Asia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Algeria.

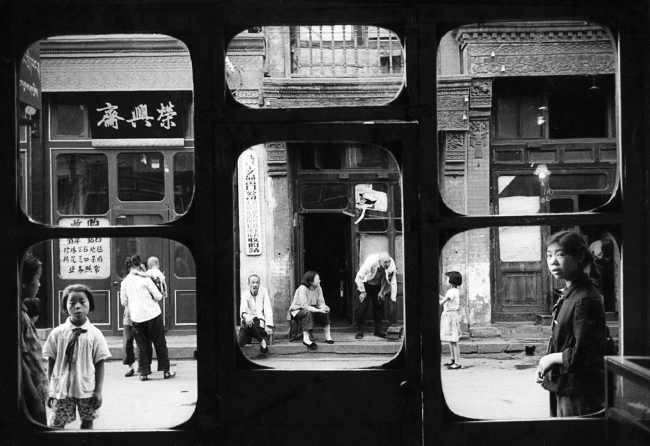

Wherever he went, his work always stressed the human element. English boys playing cowboy in the streets of London. Workers in China taking a brief break for lunch. Pilgrims at the ghats on the holy Ganges in Bénarès, India. Peasant herdsmen in Mongolia. He also shot portraits—both formal and informal—of movie stars, politicians, and diplomats, but his best work was always of common people.

“I was torn between the fear of getting too close to people and another force that egged me on to get a closer look.”

Riboud describes himself as a “shy” photographer, but over the years he’s developed some strong opinions about the practice of photography. He takes his cue from René Char, the French poet who advocated people should “foresee as a strategist and act as a primitive.” In other words, Riboud believes a photographer should mentally sketch out the scene in terms of composition, but must also be alert for the happy accident—the gesture, the turn of the head, the unexpected element—that turns an ordinary image into something extraordinary.

“Surprises of every kind lie in wait for the photographer. They open the eyes and quicken the heartbeat of those with a passion for looking.”

His best work reveals a finely-tuned sense of balance between rigorous composition and openness to the moment. Experience allows him to put himself in the right spot to take advantage of the unexpected element while retaining the strong sense of composition. One of his iconic images—a 1967 photograph of a young woman protesting against the war in Vietnam facing a stern line of armed troops standing before the Pentagon and presenting them with a flower—is a classic example of Riboud’s approach. He saw the situation as it was unfolding, took a position that provided a solid composition, and then remained poised in case a photograph presented itself.

That same approach yielded a perfect moment one morning in China as his train stopped at a station. It’s not just a matter of being in the right spot at the right moment; it’s a matter of knowing where that spot is in case the moment takes place. Riboud was aware that the windows of the train would act as frames and he was prepared when each of the frames was filled.

In 1979 Riboud resigned as a full member of Magnum, though he remains a ‘contributing member.’ He continues to shoot the things that interest him with minimal regard to the marketability of his photographs. His work hangs in museums in Europe and North America, his photos are published in magazines throughout the world, he has won awards from several international photography bodies.

At 85 years of age, Marc Riboud feels he still sees the world in the same way he did when he was 13, looking through the lens of his father’s camera. He still approaches his work the same way, though by now he’s done it so often that it’s almost instinctive. Riboud says it best: “I photograph the way a musician hums.”